Google’s War on Ad Blockers and Privacy Tools: How to Pivot to Avoid Surveillance

The global market share of the Google Chrome browser, which is expected to exceed 65% in 2024, far exceeds that of its competitors. This could explain a number of controversial decisions from a user perspective that cause problems in addition to Google’s advertising-based business model – which makes sense from the company’s point of view.

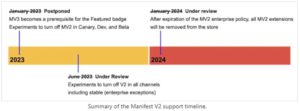

One such decision is the elimination of the Manifest V2 extension framework, which removed many privacy and security-enhancing add-ons. Competing browsers hope that Google will give them a false sense of security, knowing that Chrome users will likely accept the changes regardless of what they are offered.

In 2020, Google announced its big plan to “improve” Chrome extensions, introducing Manifest V3 with the promise of better performance, privacy, and security. But as is often the case, the devil hides in the details. The transition from Manifest V2 to V3 was a significant step, and while Google claims it’s to protect users, critics disagree. The most noticeable change? Blocking ads has been made significantly more difficult – whether intentional or not, is debatable.

Manifest V2: The Golden Age of Ad Blockers

When Chrome was still positioning itself as the “rebellious browser,” Manifest V2 provided an ideal foundation for ad blocker extensions. The webRequest API gave ad blockers the freedom to monitor network requests and efficiently block ads and tracking. This feature allowed ad blockers to act like a bouncer, stopping suspicious requests before they even load.

This “golden era” API gave ad blockers impressive control:

- Complete control over network requests: Ad blockers prevented ads from loading and thus protected against invasive trackers by intercepting requests early.

- Dynamic and targeted blocking: Ad blockers could block specifically without turning everything off at once, thus responding to user preferences and filter lists.

- Customizable filter lists: Users and communities were able to create extensive filter lists that adapted ad blockers to the ever-changing formats of online advertising. Tools like uBlock Origin thrived in this environment, providing a clean and controlled browsing experience.

However, this freedom also came with a downside: the same permissions that allowed ad blockers to block could also be abused by shady extensions. Some also argue that V2’s overhead could impact Chrome’s performance – a narrative that benefits Google.

Manifest V3: Google’s “smiling police state”

With Manifest V3, Google introduced new rules for extensions and severely restricted the use of the webRequest API, severely limiting ad blockers. Google emphasized the so-called “benefits” for performance and user protection, but critics see Manifest V3 as a move less about protecting users and more about securing revenue from online advertising.

With Manifest V3, Google has limited the “Wild West” approach to ad blocking and replaced the webRequest API with a less effective alternative: the declarativeNetRequest API. This new API essentially tells ad blockers, “Here are preset blocking rules, but no arbitrary ones!” While extensions can still block some ads, they are now limited to a fixed list of rules, significantly limiting the dynamic and granular blocking that V2 enabled.

The effects are clear:

- Less control over network requests: Under V3, ad blockers work like security guards who can only act according to a set script. Instead of analyzing requests in real time, they are limited to pre-defined rules, which reduces their effectiveness with more complex ads.

- Restricted filter lists: The declarative NetRequest API limits the number of rules to 30,000 per extension – far below the sometimes over 100,000 entries of ad blocker lists in V2.

- Fewer customization options: Custom filter lists and multi-level blocking strategies are severely limited by V3.

Google emphasizes that V3 is intended to improve “security,” leaving less room for malicious actors. But the fact that Google – one of the world’s largest data collectors – is now acting as a privacy watchdog seems ironic to many.

Privacy advocates and developers of popular ad blockers have strongly criticized V3. They see it as an attempt by Google to tighten control of the browser market under the pretext of “security” – while looking kindly at the advertisers who secure Google’s revenue. After all, advertising is Google’s main business, and fewer ad blockers could lead to higher advertising revenue, whether this is officially admitted or not.

Raymond Hill, developer of uBlock Origin, was particularly critical of the impact of V3, pointing out that the changes worsen user privacy. For him and others, blocking ads is not just about a clean layout, but about protection from tracking that follows every click and purchase online.

Is Manifest V3 really an improvement, or just different?

Whether V3 is an upgrade depends on who you ask. For advertisers, V3’s limitations are certainly welcome. For users who value control and ad-free browsing, however, V3 is a limitation.

The competition hopes to capitalize on this and attract new users. Especially since uBlock Origin, one of the most popular and effective ad blockers, is no longer fully available to Chrome users. This limitation is a direct result of Manifest V3, which replaces Chrome’s webRequest API.

The usability of a tool like uBlock Origin is crucial for many as it can significantly improve the internet experience. So it’s no surprise that when a message appeared in Chrome announcing the end of uBlock, many users wanted to switch to alternatives to Chrome.

“These extensions are no longer supported. Chrome recommends removing them,” reads the message, which lists popular ad blockers like uBlock. Apparently, the extension no longer works, even without user action – an approach that fits well with Google’s approach to users.

In Google’s world – be it in search, on video portals or on other fronts – an advertising-based business model dominates that takes on Orwellian traits: “War is peace, freedom is slavery.”

Google’s official justification for Manifest V3 is that it protects users’ privacy – but in reality it serves more to protect Google’s business interests.

uBlock Origin has not adapted to the new, controversial requirements of Manifest V3. Instead, a slimmed down version uBlock Origin Lite is offered, which is still available in Chrome.

Many users are now considering switching to another browser, with Firefox still at the top of the list – not least because of the brand’s popularity. But Mozilla had a nasty surprise in store: recently, Mozilla announced that it had removed all but the latest versions of uBlock Origin Lite – a decision that many find disappointing.

The explanation was strange, at best, and ultimately seemed aimed at putting the Lite version (the only one available in Chrome) in a bad light.

Mozilla complained about alleged “data collection” and “minified, concatenated or otherwise machine-generated code” in the add-on – which, had it been present, would have violated Mozilla’s guidelines. In fact, this was not the case. Eventually, Mozilla “re-reviewed” uBlock Lite and re-approved it.

So what could be the real alternative for users who want to switch from Chrome?

The privacy-focused Brave browser is recommended as such an alternative and offers an integrated ad blocker called Shields, which promises similar functions to the uBlock Origin extension.

The developers of the Brave browser are currently reporting a significant influx of new users joining the 70 million already worldwide. It is believed that many of the new arrivals are primarily switching from Chrome.

Although Brave is based on Chromium – the open-source base of Chrome – Brave continues to support several Manifest V2 extensions while recommending its own built-in ad blocking solution.

With Manifest V3, Google wants us to believe that it is cracking down on malicious ad blockers “in the name of privacy and performance.” However, a closer look at the alleged “improvements” reveals a different picture:

- Declarative NetRequest API: The days when ad blockers could parse all incoming requests are over. Now extensions must use predefined blocking rules and can only intercept requests-based on pre-approved policies. Google calls this a “security improvement” – ad blockers see it as a limitation.

- Limited number of rules: The new cap on filtering rules – originally 30,000, later increased to 150,000 – seems generous until you consider that many ad-blocking lists easily exceed this limit. With the increasing variety of ad formats, this is like a sieve instead of a net for ad blockers.

- “Improved performance and security”: V3 may improve performance by moving network analysis from the ad blocker to the browser, but this efficiency comes at the expense of functionality, and the supposed security benefit seems more like a byproduct of Google restricting ad blockers.

From Google’s perspective, Manifest V3 is a security win because it sets stricter rules for so-called “excessive extensions”, to prevent data leaks. But for ad blockers, the change seems like a power play: by limiting their functionality, Google controls the actions we can take in the browser.

How ad blocking differs between Manifest V2 and V3

For users who rely on an ad-free browsing experience, the difference between Manifest V2 and V3 is more than just technical – it’s a real, tangible change. With V3, ad blockers have lost practical capabilities in four key areas:

- Granularity of control

Under Manifest V2, ad blockers could dynamically respond to new ad formats as they appeared. However, V3’s static, rule-based approach makes it difficult to block dynamic ads and tracking mechanisms. Ad blockers used to be flexible enough to adapt – now ad engineers have more options to get through unnoticed.

- Limited filter lists

V2 offered the freedom to use extensive, community-maintained filter lists with thousands of entries. With V3, the cap is now 150,000 rules, which is often not enough given the ingenuity of the advertising industry. This limit forces ad blockers to choose their filters carefully to cope with the abundance of ads and trackers.

- Resource utilization

Google touts V3 as a more efficient solution that reduces memory and CPU load by offloading network processing to the browser. However, this efficiency improvement only comes about because ad blockers are prevented from performing resource-intensive tasks. The performance improvements come at the direct cost of functionality – a “solution” that was only necessary because V3’s restrictive framework limits blockers.

- Data protection concerns

Despite Chrome’s emphasized security features, V3 has alarmed privacy advocates. The reduction in granular filtering means that ad blockers are limited in their ability to block tracking scripts outright. With V3, more trackers can now slip through, increasing the risk of third-party data collection and putting user privacy at risk.

The User Experience: How Manifest V3 Feels in Practice

For users who have grown accustomed to a clean, ad-free browsing experience, Manifest V3 brings an unwelcome change. Even the most popular ad blockers, limited by V3, can no longer block every ad. Ads that use more sophisticated techniques are more likely to be able to bypass the new rules, leading to more interruptions. Customization options for ad blockers have also been limited, so users who rely on custom filter lists will find V3 a significant downgrade.

The experience is further marred by a now-familiar Chrome message: “These extensions are no longer supported. Chrome recommends that you remove them.” Google’s suggestion to disable V2-based ad blockers feels like an ultimatum, urging users to accept the new regime or switch to another browser.

yogaesoteric

November 16, 2024