China found an energy source in US archives that could power its future for 20,000 years – and implemented it

In the 1960s, the US – more precisely, the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee – invented a revolutionary type of nuclear reactor that could be powered by thorium instead of uranium (much more abundant and cheaper), with no risk of meltdown, 50 times less waste, and no need for water. Then, due to chaotic politics, they killed the program in 1969 and fired the visionary behind it.

The declassified blueprints for the project then lay forgotten in archives for decades. That is, until Chinese scientists found them and decided in 2011 to launch an experimental project in the Gobi Desert to see if they could make it work.

This month (November 2025), after 14 years of work, they finally succeeded.

Here is the full story – how the technology works, the bureaucratic politics that killed it in America, and why this could really be a big transformation.

The technology

Let me first explain conventional nuclear power, because I have noticed in discussions over the last few days that many people are not familiar with how it works.

A conventional nuclear power plant is basically like a giant kettle. At its core, that’s exactly what it is: You trigger a nuclear chain reaction in uranium fuel elements (atoms split and release particles that split more atoms, i.e., “fission”), this generates an enormous amount of heat, you use this heat to turn water into steam, and the steam drives turbines to generate electricity.

It’s quite funny: many people don’t realize that a nuclear power plant isn’t technologically that different from the steam engine of the 18th century. It’s the same basic concept, where steam does the work, only instead of burning coal to heat the water, we use uranium fuel elements.

Simple enough in theory, but, as we all know, conventional nuclear power has some pretty big disadvantages in practice:

- Safety. We all know this one: Conventional nuclear power plants have the annoying tendency to melt down, rendering entire regions radioactive and uninhabitable for long time. Which is, let’s say, less than ideal. Well, it only occurred twice in history, but the risk is still real.

- Uranium shortage. This is relatively rare and concentrated in only a few countries (Kazakhstan, Canada, Namibia and Australia – together produce 80% of the world’s uranium).

- Fuel inefficiency. Conventional reactors extract only about 1-3% of the energy from the uranium before the fuel rods are “burned out”. Literally 97-99% of the fuel is discarded as radioactive waste.

- Nuclear waste. The spent fuel remains lethally radioactive for tens of thousands of years. We have no permanent storage solutions, only temporary facilities and a great deal of – probably naive – optimism that future generations will find a solution.

Because of all these disadvantages, scientists have been searching for alternatives for decades. And indeed, they found one as early as the 1940s at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, a research and development centre funded by the US state.

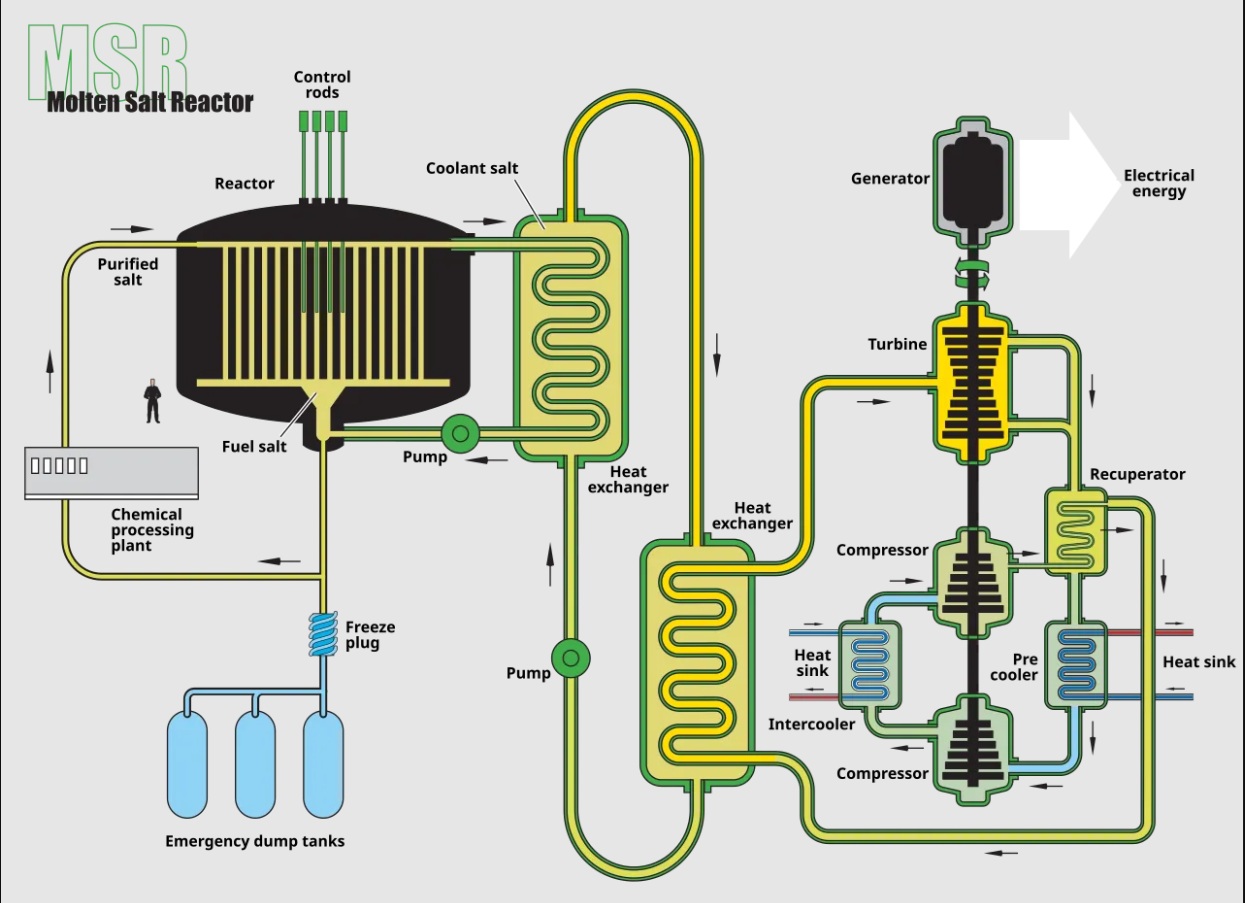

The idea was actually quite simple: If melting – that is, the uranium fuel elements becoming so hot that they melt – is the main danger of conventional nuclear power plants, why not liquefy the nuclear fuel? There’s nothing to melt if it’s already molten… And that’s how the basic idea of the Molten Salt Reactor (MSR) came about.

Here’s how it works: Special salts (like fluoride salts) are heated until they melt into a liquid at around 500°C. Then, the nuclear fuel (thorium or uranium) is dissolved directly into this molten salt, and the nuclear chain reaction takes place right there in the liquid – atoms split, releasing heat and heating the salt itself.

How is this safer, I ask? Thanks to a rather clever design where the reactor floor itself consists of unmolten salts that would melt if the molten salt overheated (the “freeze plug” you see in the diagram above). And if these unmolten salts melted, the overheated molten salt would automatically fall – by gravity alone – into emergency tanks, whose geometry (they are wide, shallow containers) would automatically stop the nuclear reaction.

Imagine it like this: For the sake of argument, imagine you’re making a campfire – a tight bundle of burning sticks – on a thick layer of ice, several meters below which lies a sheet of flat concrete. If your campfire gets too hot, the ice melts and your sticks spread out flat on the concrete below: The fire goes out because it can’t jump between the sticks. A pretty similar concept.

To be clear: In this MSR concept, these hot molten salts, mixed with nuclear fuel, still ultimately have to heat water (or another gas, as we’ll see later) to steam in order to drive turbines and generate electricity – the same basic principle as in conventional reactors. But here’s the crucial difference: The radioactive molten salt flows through metal pipes in a heat exchanger, where it heats clean water on the other side, without the two ever mixing. This means the radioactive salts remain completely separate in their own closed loop, while only clean, non-radioactive steam reaches the turbines. If there’s a leak in the steam system, no radioactive material is released into the environment, only clean water.

There is another, equally important but less obvious safety advantage: MSRs operate at atmospheric pressure – the same pressure as the air around us. Conventional reactors run at 150+ atmospheres because they use water as a coolant, and keeping water liquid at 300°C+ – three times its normal boiling point – requires crushing pressure. This means conventional reactors need massive steel pressure vessels with walls up to a foot thick, weighing hundreds of tons. And if these vessels ever fail, there is a massive explosion: a bit like a burst tire, only on the scale of a nuclear power plant and with the release of deadly radioactive elements everywhere. Compared to that, if an MSR pipe leaks, you get just a slow drop of molten salt that solidifies on contact with air: annoying, but not catastrophic.

This also has a massive impact on cost-effectiveness: The pressure vessel alone accounts for a large portion of the costs of conventional nuclear power plants, which cost $6-10 billion each (or, in the case of Vogtle, the last US nuclear power plant, $18 billion each) and require a decade of construction time (11 years in the case of Vogtle). Eliminating the pressure requirement makes MSRs dramatically cheaper and faster to build.

That was the safety aspect. How are the other disadvantages solved? Let’s look at the uranium shortage and the fuel inefficiency.

The immense advantage of MSRs is that, unlike conventional reactors, they can use thorium instead of uranium. This is a huge advantage because thorium is a much more abundant element than uranium: it occurs in the Earth’s crust at approximately 9-10 parts per million (ppm) – about as abundant as lead – compared to only 2-3 ppm for uranium.

A crucial aspect to understand, however, is that thorium, unlike uranium, is NOT a so-called “fissile” material, meaning it cannot sustain a nuclear chain reaction on its own. It is merely “breeding,” meaning it can become “fissile,” but only after a transformation, in this case into uranium-233.

This is called “breeding” – creating nuclear fuel from non-fuel. The conversion process works like this: When a thorium-232 atom absorbs a neutron (remember, neutrons are constantly moving around in an active reactor from fissioning atoms), it becomes thorium-233. Then, thorium-233 naturally decays – in about 22 minutes – into protactinium-233. Then, protactinium-233 decays – in about 27 days – into uranium-233. And voilà: uranium-233 is fissionable, which means it can now split and sustain the chain reaction. So, in about a month, you’ve converted a non-fuel atom (thorium) into a fuel atom (uranium-233) simply by leaving it in the reactor to absorb neutrons. As long as thorium continues to be supplied and it continues to absorb neutrons, new fuel is continuously being cultivated.

Wait a minute, why can’t this “breeding” and conversion of thorium-232 into fissile uranium-233 be done in a conventional reactor? Theoretically, it could, but there’s an insurmountable problem: you can’t achieve a self-sustaining breeding cycle with solid fuel. So you would breed some U-233, but not enough to both sustain the reaction AND breed even more U-233 from fresh thorium. You’d remain dependent on imported uranium, which defeats the whole purpose.

The beauty of MSRs, however, lies in the fact that, because the fuel is liquid and fluid, fresh thorium can be continuously added. The uranium-233 forms in the liquid and immediately participates in the nuclear chain reaction AND in the production of more uranium-233 from thorium, while the whole process continues and generates energy. Essentially, a perpetual motion machine for nuclear fuel has been created: The reactor makes its own fuel from thorium while simultaneously running on this fuel and breeding more of it.

There is another major advantage. Remember how conventional reactors only extract about 1-3% of the energy from the uranium before the fuel rods are “burned out”? This is because fission waste products accumulate in the solid fuel and poison the reaction, stopping it, a bit like bread dough rising once too much CO2 accumulates – the waste product of the reaction eventually suffocates the reaction itself.

This problem doesn’t exist with MSRs because, in a liquid fuel system, fission waste products can be chemically removed from the flowing molten salt while the reactor continues to operate, thus extracting nearly 99% of the fuel’s energy instead of wasting 97-99%. That’s a 30-50-fold improvement in fuel efficiency!

This means that our nuclear waste problem is also largely solved. First, there is 30-50 times less waste because 30-50 times more energy is extracted from the fuel – simple math. Second, the small amount of remaining waste is nowhere near as dangerous: unlike the waste from conventional reactors, which remains dangerously radioactive for tens of thousands of years (longer than recorded human history), MSR waste only needs safe storage for 300-500 years. Still a long time, but building repositories that last for a handful of centuries is a relatively trivial engineering challenge; we know how to do that, whereas we don’t know how to build something that will remain safe for potentially 100,000 or 200,000 years.

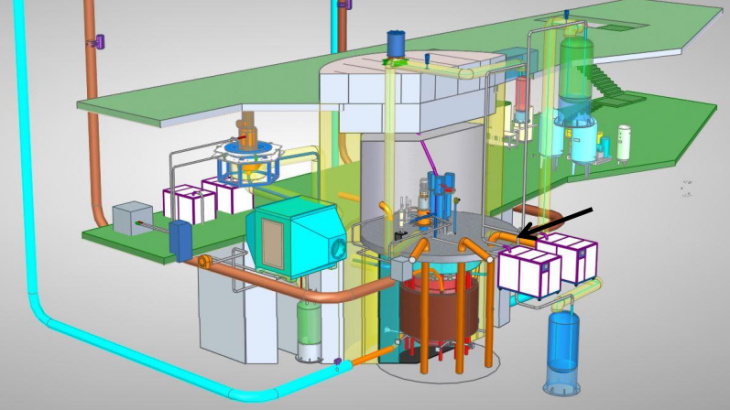

One final critical point: Unlike conventional reactors, MSRs do not need to be built next to massive water sources; they can essentially be built anywhere. In fact, China’s “TMSR-LF1” MSR reactor – the groundbreaking project we are discussing – is located in Minqin County, Gansu Province, one of the driest regions in China, right on the edge of the Gobi Desert.

Wait a minute, I hear you say, I thought MSRs also had to heat water to steam to drive turbines and generate electricity? Well, not always: remember how I added the caveat “or another gas, as we’ll see later”? That’s the case here. The current reactor, as it stands, is a demonstration project testing the thorium fuel cycle without generating electricity (so there’s no turbine), but China is already starting to build the actual power plant on the same site: a 60 MW reactor that will produce 10 MW of electricity using supercritical carbon dioxide turbines instead of traditional steam. The CO2 remains in a closed pressurized loop – hot molten salt heats it, it drives the turbine, air cooling cools it down, and it circulates again. Nowhere in the system is water needed.

Specifically, this means that MSRs can be deployed in China’s water-scarce western provinces (such as northern Gansu in this case), in Central Asian deserts along the Belt and Road routes, or even on the moon (yes, really!). Anywhere strategic necessity dictates it, regardless of water availability.

Well, I admit, that got a little technical. But you needed to understand what MSRs actually do and why they’re revolutionary – otherwise, this article wouldn’t make much sense.

One aspect I haven’t explained, however, is the fate of the Oak Ridge program: Why did America invent such a promising technology, successfully demonstrate it, and then shut down the program and publicly publish all the research results? That’s the great irony: China’s MSR program – which could be the key to its future – is based on discredited American blueprints.

The Oak Ridge Program

Here’s what makes this story particularly “facepalming”-worthy when viewed from an American perspective, especially if MSRs deliver on their promise and prove to be highly consequential for China’s energy future: America didn’t just theorize about molten salt reactors, they actually built one!

In Oak Ridge in the 1960s, Director Alvin Weinberg sincerely believed that MSRs were the future of nuclear power. He convinced the Atomic Energy Commission to fund a proper test. The Molten Salt Reactor Experiment (MSRE) ran from 1965 to 1969 – four years, with over 13,000 operating hours. They proved that the concept worked. The molten salt fuel system was stable. The passive safety features worked exactly as designed (the ones I explained above with the campfire-on-ice analogy).

They never demonstrated the full breeding cycle – the conversion of thorium to uranium-233 in a running reactor – but they had proven enough that the path forward was clear. Weinberg pressed on. He had the data. He had the operational experience. He had a technology that could solve the biggest problems of nuclear power.

Then came politics.

In the early 1970s, the Nixon administration had decided that the future belonged to the Liquid Metal Fast Breeder Reactor (LMFBR) – a competing nuclear-breeding technology. The man tasked with making this take place was Milton Shaw, who headed the reactor division of the Atomic Energy Commission. Shaw was a protégé of Admiral Rickover – the notoriously aloof father of the nuclear navy. He had completely absorbed his mentor’s leadership style: My way, no discussion, and if you’re not with me, you’re against me.

Weinberg continued to advocate for molten salt reactors. Worse still, he repeatedly and publicly pointed out safety problems with the conventional reactors being built everywhere – the kind of truth-telling that makes bureaucrats nervous. This made him inconvenient.

In Weinberg’s own words: “It was clear that [Shaw] had little confidence in me or, in that respect, in the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After all, we were pushing for molten salt, not LMFBR.”

He was fired in 1973. By that time, the molten salt reactor was already dead – Shaw had forced its closure in 1969.

Shaw’s team produced a report (WASH-1222) stating that MSRs “required too much development,” while LMFBRs were touted as the “mature technology” that America should pursue. Forget that MSRs had actually been running for several years, while LMFBRs were still in the planning stages. Political decisions don’t require logical consistency.

And sure enough, it proved to be a bad choice: The “mature” LMFBR technology, on which the US had staked everything, led absolutely nowhere. They tried to develop a project around it, the Clinch River Breeder Reactor, which was approved in 1970 with initial costs of $400 million. By 1983, the costs had exploded to $8 billion, with no end in sight. Congress cut funding in October 1983 – the reactor was never completed, and not a single watt of electricity was ever generated.

America’s loss was made possible, in the most literal way, by China’s gain. Oak Ridge, as is customary for any such project, had documented its work in hundreds of technical reports – semi-annual progress reports from 1958 to 1967, detailed engineering specifications, materials science data, and MSRE operational logs. After the program’s cancellation in 1976, these reports became publicly available and, for the most part, lay forgotten in engineering libraries and archives.

In 2002, Kirk Sorensen, an aerospace engineer at NASA, discovered them and – together with his colleague Bruce Patton – received funding to have them digitized. By 2006, Sorensen had created energyfromthorium.com and made everything available online as a public repository. Free of charge. Accessible to everyone.

China used this publicly available American research as the basis for its MSR program – a fact it openly acknowledges. Xu Hongjie, the lead scientist of the Chinese MSR project, said at a meeting of the Chinese Academy of Sciences earlier this year: “The US left its research publicly available and waited for the right successor. We were that successor.”

Good enough – groundbreaking science shouldn’t gather dust for half a century just because one country lost its interest in it. If America wasn’t prepared to see Weinberg’s vision through to completion, someone else should. That someone turned out to be China.

China’s latest breakthrough

China didn’t simply dust off the Oak Ridge blueprints and create a replica. They did what Weinberg never had the chance to finish: they completed the cycle.

Remember the critical missing piece of the puzzle from the Oak Ridge experiment? The MSRE proved that a molten salt reactor could be operated. It proved that the safety systems worked. It even proved that uranium-233 could be used as fuel. But it never demonstrated the self-sustaining breeding cycle – the reactor that continuously generates its own fuel from thorium while running, the “perpetual motion machine” I described earlier. That was the essence, the element that would make the whole concept revolutionary rather than just interesting.

China reached it at the beginning of this month.

Their TMSR-LF1 reactor in Gansu successfully completed the world’s first thorium-to-uranium conversion in an operating molten salt reactor. The Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences announced that they had obtained valid experimental data proving that the thorium fuel cycle works – thorium-232 continuously capturing neutrons and converting into uranium-233 in the running reactor.

This may sound like an incremental step – “fine, they did the brood element, so what?” But understand what this unleashes: It proves that the thorium fuel cycle works. It means that China can now, in principle, design and build reactors that can run indefinitely on domestically produced thorium, without dependence on foreign uranium supplies and without vulnerability to supply chain disruptions.

In fact, according to Cai Xiangzhou, deputy director of the Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics (which is leading the project), China has virtually ZERO external dependence on the technology: “Over 90 percent of the reactor’s components are produced domestically, with 100 percent localization of key parts and a completely independent supply chain. This success marks the initial establishment of an industrial ecosystem for thorium molten salt reactor technologies in China.”

And that’s without even mentioning thorium itself, of which China has massive reserves. Some estimates suggest enough to power the country for 20,000 to 60,000 years. That’s not a typo. Tens of thousands of years of energy independence from domestic resources, with technology that China now controls end-to-end.

To be clear, we still have a long way to go. The current TMSR-LF1 is a 2-megawatt thermal demonstration reactor – it proves that the breeding cycle works, but it doesn’t generate electricity. It’s essentially a proof of concept: “Yes, we can breed uranium-233 from thorium in a molten salt reactor.” A critical milestone, but not yet a power plant.

The next step is already underway. Construction began this year at the same site in Gansu with what is effectively the bigger brother of TMSR-LF1: a reactor that will add the power generation component. It is designed to produce 10 MW of electrical power, using the previously mentioned supercritical carbon dioxide (sCO2) turbines.

What’s truly remarkable, and what really highlights China’s level of ambition in this project, is that sCO2 turbines are cutting-edge technology themselves. In fact, as far as I can tell, this would be the world’s first nuclear power plant to utilize this turbine technology for electricity generation. According to the Wisconsin Energy Institute, replacing traditional steam turbines with closed-loop sCO2 gas turbines could increase power generation efficiency by 50 percent or more – a transformative improvement for any power generation technology.

So China is simultaneously demonstrating a brand-new nuclear reactor technology (thorium-breeding MSRs) AND a revolutionary turbine technology (supercritical CO2), and they’re building it all as an integrated power plant in the Gobi Desert.

If this works – and the most complicated part of it just has – China will have bypassed conventional nuclear power entirely and entered a completely new category of electricity generation. Not only safer and cheaper than traditional reactors, but fundamentally more efficient at converting heat into electricity. And of course, again, all using the abundant thorium as the energy source.

The final step is demonstrating commercial readiness. Cai Xiangzhou says the goal is “to complete the construction and demonstration operation of a 100-megawatt thermal prototype and achieve commercial application by 2035.” A 100 MW reactor is small by conventional nuclear standards – most modern reactors are 1,000+ MW – but it is large enough to validate economic viability and operational characteristics for commercial use.

If a 100 MW thorium MSR can operate reliably and produce electricity at competitive costs, then China will have everything it needs to build these reactors commercially. And since they control the entire domestic supply chain – from the thorium itself to every key component – there is theoretically no technical or geopolitical obstacle that could prevent them from building dozens, then hundreds, of these reactors across the country.

To be clear, theoretically, MSR-generated energy should be much cheaper than conventional nuclear power (which is already comparatively cheap). It makes sense: thorium is cheaper than uranium, fuel utilization is 30-50 times better, MSRs will be much cheaper to build (remember: no massive pressure vessel), refuelling can be done online during operation, and so on. Of course, years of bug fixing, unforeseen technical challenges, and the brutal reality of actual operation separate “theoretically” from “in practice.” China is making a massive bet that this theory can be translated into practice. But if they are right – and nothing so far suggests they aren’t – they will have at least a decade’s head start on everyone else.

The long-term consequences

If the MSR bet pays off, what this could mean for China’s strategic position in the long term is almost too enormous to comprehend.

First, the obvious: independence from energy bottlenecks. No Strait of Hormuz. No Strait of Malacca. No vulnerability to maritime blockades of oil supplies.

Secondly, it’s not just about electricity generation: cheap, abundant energy is transforming every energy-intensive industry. Aluminium smelting, steel production, the chemical industry, semiconductor manufacturing, operating AI data centres – all of this will be structurally even cheaper to operate in China than it already is. Even cargo shipping: just a few weeks ago, China announced plans to build the world’s largest cargo ship, powered by……. you guessed it: a thorium-based molten salt reactor!

The country, which already dominates global production capacity, would gain a further insurmountable cost advantage in the most strategic industries of the 21st century.

Third: Deployment flexibility. China could build these safe nuclear power plants anywhere – Tibet, Xinjiang, the inland deserts, cargo ships, the moon, anywhere strategic necessity dictates. Central Asian countries with no water resources but plenty of desert? Perfect MSR candidates. Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan – all potential customers for safe, Chinese-built thorium reactors that require no fuel imports or water and pose no meltdown risk.

Fourth, the cascading effects on other technologies. Abundant cheap electricity is making previously uneconomical processes profitable. For example, large-scale hydrogen production for industry and transportation. It is probably no coincidence that the first 10 MW experimental reactor, currently under construction in Gansu, is already planned to produce so-called “purple hydrogen,” a way to store energy as hydrogen that can then be used as fuel for many applications. Traditional hydrogen production is expensive, but the bet is clearly that MSRs could make hydrogen production more efficient and economically viable.

But above all, this MSR project illustrates a deeper story: that of a China that dares to go where the West gives up. It’s not just about MSRs: across virtually all energy sources, across virtually every conceivable area, we see the same dynamic. We live in a world where the bureaucracy and the lack of grand vision, of ideals, are not found in the country led by the Communist Party, but in the West.

The story of how China embraced Weinberg’s dream is almost painfully symbolic. The blueprints for energy abundance gathered dust in archives because they didn’t fit the political moment and were killed by bureaucracy. And here is China, methodically working through these declassified American documents, solving the problems Oak Ridge was never allowed to finish, and building in Gansu the future Tennessee abandoned. A rising civilization, literally unearthing and reviving the abandoned dreams of a seriously struggling one.

Author: Arnaud Bertrand

yogaesoteric

November 29, 2025

Also available in:

Română

Română