Can Autoimmune Antibodies Explain Blood Clots in COVID-19?

For people with severe COVID-19, one of the most troubling complications is abnormal blood clotting that puts them at risk of having a debilitating stroke or heart attack. A new study suggests that SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, doesn’t act alone in causing blood clots. The virus seems to unleash mysterious antibodies that mistakenly attack the body’s own cells to cause clots.

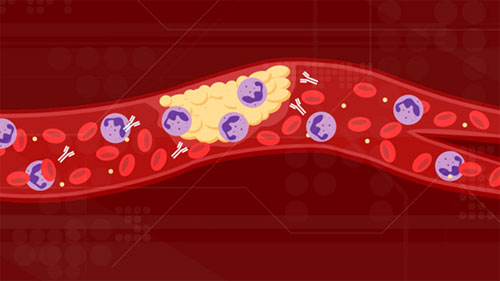

Illustration showing a blood vessel with a platelet clot (yellow). Red blood cells (red), neutrophils (purple), and Y-shaped antibodies called aPL (white) circulate through the vessel. Credit: Stephanie King/Michigan Medicine

The NIH-supported study, published in Science Translational Medicine, uncovered at least one of these autoimmune antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies in about half of blood samples taken from 172 patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Those with higher levels of the destructive autoantibodies also had other signs of trouble. They included greater numbers of sticky, clot-promoting platelets and NETs, webs of DNA and protein that immune cells called neutrophils spew to ensnare viruses during uncontrolled infections, but which can lead to inflammation and clotting. These observations, coupled with the results of lab and mouse studies, suggest that treatments to control those autoantibodies may hold promise for preventing the cascade of events that produce clots in people with COVID-19.

Our blood vessels normally strike a balance between producing clotting and anti-clotting factors. This balance keeps us ready to seal up vessels after injury, but otherwise to keep our blood flowing at just the right consistency so that neutrophils and platelets don’t stick and form clots at the wrong time. But previous studies have suggested that SARS-CoV-2 can tip the balance toward promoting clot formation, raising questions about which factors also get activated to further drive this dangerous imbalance.

To learn more, a team of physician-scientists, led by Yogendra Kanthi, a newly recruited Lasker Scholar at NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and his University of Michigan colleague Jason S. Knight, looked to various types of aPL autoantibodies. These autoantibodies are a major focus in the Knight Lab’s studies of an acquired autoimmune clotting condition called antiphospholipid syndrome. In people with this syndrome, aPL autoantibodies attack phospholipids on the surface of cells including those that line blood vessels, leading to increased clotting. This syndrome is more common in people with other autoimmune or rheumatic conditions, such as lupus.

It’s also known that viral infections, including COVID-19, produce a transient increase in aPL antibodies. The researchers wondered whether those usually short-lived aPL antibodies in COVID-19 could trigger a condition similar to antiphospholipid syndrome.

The researchers showed that’s exactly the case. In lab studies, neutrophils from healthy people released twice as many NETs when cultured with autoantibodies from patients with COVID-19. That’s remarkably similar to what had been seen previously in such studies of the autoantibodies from patients with established antiphospholipid syndrome. Importantly, their studies in the lab further suggest that the drug dipyridamole, used for decades to prevent blood clots, may help to block that antibody-triggered release of NETs in COVID-19.

The researchers also used mouse models to confirm that autoantibodies from patients with COVID-19 actually led to blood clots. Again, those findings closely mirror what happens in mouse studies testing the effects of antibodies from patients with the most severe forms of antiphospholipid syndrome.

While more study is needed, the findings suggest that treatments directed at autoantibodies to limit the formation of NETs might improve outcomes for people severely ill with COVID-19. The researchers note that further study is needed to determine what triggers autoantibodies in the first place and how long they last in those who’ve recovered from COVID-19.

The researchers have already begun enrolling patients into a modest scale clinical trial to test the anti-clotting drug dipyridamole in patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19, to find out if it can protect against dangerous blood clots. These observations may also influence the design of the ACTIV-4 trial, which is testing various antithrombotic agents in outpatients, inpatients, and convalescent patients. Kanthi and Knight suggest it may also prove useful to test infected patients for aPL antibodies to help identify and improve treatment for those who may be at especially high risk for developing clots. The hope is this line of inquiry ultimately will lead to new approaches for avoiding this very troubling complication in patients with severe COVID-19.

yogaesoteric

November 30, 2020