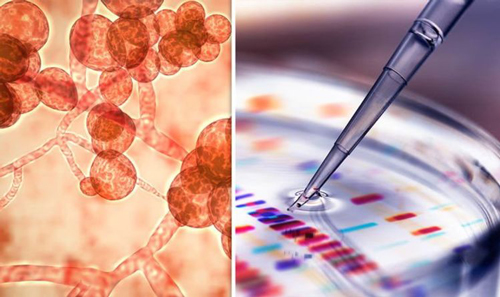

Candida Auris: The Incredibly Deadly Fungus Killing People across the Planet

A “mysterious and dangerous” fungal infection has emerged, and experts are warning that it is a serious global health threat.

In “A Mysterious Infection, Spanning the Globe in a Climate of Secrecy”, The New York Times outlines the terrifying details:

“The germ, a fungus called Candida auris, preys on people with weakened immune systems, and it is quietly spreading across the globe. Over the last five years, it has hit a neonatal unit in Venezuela, swept through a hospital in Spain, forced a prestigious British medical center to shut down its intensive care unit, and taken root in India, Pakistan and South Africa.

Recently C. auris reached New York, New Jersey and Illinois, leading the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to add it to a list of germs deemed ‘urgent threats’.”

This fungal infection is extremely difficult to kill.

Last May, an elderly man became infected with C. auris and doctors were not able to save him. What happened after his death is horrifying: “The man at Mount Sinai died after 90 days in the hospital, but C. auris did not. Tests showed it was everywhere in his room, so invasive that the hospital needed special cleaning equipment and had to rip out some of the ceiling and floor tiles to eradicate it.

‘Everything was positive — the walls, the bed, the doors, the curtains, the phones, the sink, the whiteboard, the poles, the pump’, said Dr. Scott Lorin, the hospital’s president. ‘The mattress, the bed rails, the canister holes, the window shades, the ceiling, everything in the room was positive’.”

In late 2015, a similar case occurred at Royal Brompton Hospital, a British medical center outside London. Workers there used a special device to spray aerosolized hydrogen peroxide around a room used for a patient with C. auris. In hopes that the vapor would disinfect the room, they left the device running for a week. When they tested the room to see if any microbes survived, they found only one: C. auris.

C. auris is a serious emerging public health threat. It is the latest addition to the ever-growing list of one of the world’s most dangerous health threats: the rise of drug-resistant infections.

“It’s an enormous problem,” said Matthew Fisher, a professor of fungal epidemiology at Imperial College London, who was a co-author of a recent scientific review on the rise of resistant fungi. “We depend on being able to treat those patients with antifungals.”

The CDC is concerned about C. auris for three main reasons, according to the agency’s website:

1. It is often multidrug-resistant, meaning that it is resistant to multiple antifungal drugs commonly used to treat Candida infections.

2. It is difficult to identify with standard laboratory methods, and it can be misidentified in labs without specific technology. Misidentification may lead to inappropriate management.

3. It has caused outbreaks in healthcare settings. For this reason, it is important to quickly identify C. auris in a hospitalized patient so that healthcare facilities can take special precautions to stop its spread.

Until March 29, 2019, 617 cases of C. auris have been reported to the CDC.

Here’s why you might not have heard of this until now.

C. auris seems like something the public should be warned about, doesn’t it?

Officials have been trying to avoid talking about it much for various reasons.

The NYT explains why there is so much secrecy surrounding C. auris:

“With bacteria and fungi alike, hospitals and local governments are reluctant to disclose outbreaks for fear of being seen as infection hubs. Even the C.D.C., under its agreement with states, is not allowed to make public the location or name of hospitals involved in outbreaks. State governments have in many cases declined to publicly share information beyond acknowledging that they have had cases.”

Some health officials claim that notifying the public about outbreaks will cause unnecessary fear. But others say that people have the right to know if there are local cases so they can avoid going to impacted facilities. Hospitals that have had cases worry about their reputation and tend to avoid publicizing cases of C. auris for that reason.

Overuse of certain medications appears to be making C. auris stronger.

Just as antibiotic overuse has contributed to the rise of resistant bacteria, overuse of antimicrobial drugs is helping fungi becoming resistant:

“Scientists say that unless more effective new medicines are developed and unnecessary use of antimicrobial drugs is sharply curbed, risk will spread to healthier populations. A study the British government funded projects that if policies are not put in place to slow the rise of drug resistance, 10 million people could die worldwide of all such infections in 2050, eclipsing the eight million expected to die that year from cancer.”

While antifungals are life-saving drugs, they are also applied to prevent agricultural plants from rotting. There is evidence that suggests the rampant use of fungicides on crops is contributing to the surge in drug-resistant fungi infecting humans, according to scientists.

Dr. Jacques Meis, a microbiologist in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, is one of those scientists:

“Dr. Meis became intrigued by resistant fungi when he heard about the case of a 63-year-old patient in the Netherlands who died in 2005 from a fungus called Aspergillus. It proved resistant to a front-line antifungal treatment called itraconazole. That drug is a virtual copy of the azole pesticides that are used to dust crops the world over and account for more than one-third of all fungicide sales.

A 2013 paper in Plos Pathogens said that it appeared to be no coincidence that drug-resistant Aspergillus was showing up in the environment where the azole fungicides were used. The fungus appeared in 12 percent of Dutch soil samples, for example, but also in ‘flower beds, compost, leaves, plant seeds, soil samples of tea gardens, paddy fields, hospital surroundings, and aerial samples of hospitals’.”

Experts still aren’t sure where C. auris comes from or how it spreads.

According to the CDC, nearly half of patients who contract C. auris die within 90 days. But experts still aren’t sure where it came from:

“It is a creature from the black lagoon,” said Dr. Tom Chiller, who heads the fungal branch at the CDC, which is spearheading a global detective effort to find treatments and stop the spread. “It bubbled up and now it is everywhere.”

The CDC explains who is at risk of infection from C. auris:

“Limited data suggest that the risk factors for Candida auris infections are generally similar to risk factors for other types of Candida infections. These risk factors include recent surgery, diabetes, broad-spectrum antibiotic and antifungal use. People who have recently spent time in nursing homes and have lines and tubes that go into their body (such as breathing tubes, feeding tubes and central venous catheters), seem to be at highest risk for C. auris infection. Infections have been found in patients of all ages, from preterm infants to the elderly. Further study is needed to learn more about risk factors for C. auris infection.”

C. auris can spread in healthcare settings through contact with contaminated environmental surfaces or equipment, or from person to person. More work is needed to further understand how it spreads, according to the CDC.

The symptoms of C. auris – fever, aches, and fatigue – are not unusual, so it is hard to recognize the infection without testing. And, some people can be carriers who don’t develop symptoms at all.

We’ve long been warned about the growing threat of drug-resistant infections.

Now it seems like more are emerging at an alarming rate.

According to the NYT:

“In the United States, two million people contract resistant infections annually, and 23,000 die from them, according to the official C.D.C. estimate. That number was based on 2010 figures; more recent estimates from researchers at Washington University School of Medicine put the death toll at 162,000. Worldwide fatalities from resistant infections are estimated at 700,000.”

If you read the NYT report about C. auris, it immediately makes you think of another horrifying disease that is rapidly becoming a public health threat. Recently, experts warned the public about “zombie deer” disease (Chronic Wasting Disease, or CWD).

CWD is a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy disease found in deer, elk, moose, reindeer, and caribou. It is a progressive disease that always kills its victims.

The disease is believed to be caused by abnormal proteins called prions, which are thought to cause damage to other normal prion proteins that can be found in tissues throughout the body. They are most often found in the brain and spinal cord, leading to brain damage and development of prion diseases. Infected brain cells eventually burst, leaving behind microscopic empty spaces in the brain matter that give it a “spongy” look.

As of March 6, 2019, there were 270 counties in 24 states with reported CWD, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s update.

Prions are misfolded proteins that are somehow infectious (we’re still not really sure how or why) and for which we have no treatments or cures. If you were to catch one, you’d basically deteriorate over the course of several months, possibly losing the ability to speak or move, and eventually, you would die. Doctors wouldn’t be able to do anything to save you.

Like C. auris, CWD is extremely difficult – if not impossible -to kill. Antibiotics do not kill CWD. Neither does cooking.

To give you an idea of just how persistent prions are: In 1985, the Colorado Division of Wildlife tried to eliminate CWD from a research facility by treating the soil with chlorine, removing the treated soil, and applying an additional chlorine treatment before letting the facility remain vacant for more than a year. Those efforts failed – they were unsuccessful in eliminating CWD from the facility.

Health officials have also recently raised serious concerns about the spread of “medieval diseases” that are resurging in some parts of the US.

yogaesoteric

June 8, 2019

Also available in:

Français

Français