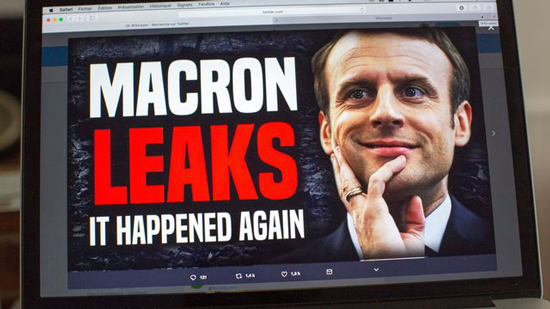

Emmanuel Macron To Create France’s First ‘Ministry Of Truth’

French President Emmanuel Macron has unveiled plans to introduce France’s first ever Ministry of Truth in order to combat misinformation online.

The draft law, designed to stop what Macron calls “manipulation of information” in the run-up to elections, will be debated in parliament and then put into action during next year’s European parliamentary polls.

The law is the brainchild of Macron himself, who claims he was targeted during the 2017 campaign by “false rumors” that he was gay and had a secret bank account in the Bahamas (“rumors” that turned out to be true).

AFP reports that under the law, French authorities would be able to immediately halt the publication of information deemed to be false ahead of elections.

Social networks would have to introduce measures allowing users to flag up false reports, pass their data on such articles to authorities, and make public their efforts against fake news.

And the law would authorize the state to take foreign broadcasters off the air if they were attempting to destabilize France – a measure seemingly aimed at Russian state-backed outlet RT in particular.

Censorship?

European governments have struggled to work out how to respond to the fake news phenomenon, not least after accusations of Kremlin meddling in France and the US presidential vote that brought Donald Trump to power.

The British government has set up a “fake news” unit, while Italy has an online service to report false articles and the European Union is working on a “code of practice” that would provide guidelines for social media companies.

France wants to go further – though not as far as neighboring Germany, where social networks face fines of up to 50 million euros ($58 million) under a controversial law which critics say is overly draconian.

Some opponents fear French authorities could use powers in the new law to block embarrassing or compromising reports.

“It’s a step towards censorship”, said Vincent Lanier, head of France’s national journalists’ union, the SNJ. He labelled the bill “inefficient and potentially dangerous”.

The government insists measures will be built into the law to protect freedom of speech, with only reports that are “manifestly false” and that have gone viral – notably with the help of bots – taken down.

“Reducing freedom of expression is not the idea at all. On the contrary, it’s to protect it”, said Culture Minister Francoise Nyssen.

Leaving fake news to spread would be a “direct attack” on journalism, she argued.

But for Jerome Fenoglio, editorial director of Le Monde newspaper, the legislation carries too big a risk of suppressing information in the public interest.

“Elections should be a time of great freedom – these are periods when important information emerges” he said, noting as an example the fake jobs scandal that torpedoed the campaign of presidential frontrunner Francois Fillon last year.

“We should be worried about an authoritarian regime winning power in France in the future and the methods it might use”, he said.

Arbiters of truth

Others worry the law could backfire by giving extra credibility to reports labelled “fake” by the authorities amongst those convinced the government is out to hide the truth.

Fabrice Epelboin, who teaches media studies at Sciences Po university in Paris, predicts “catastrophic consequences” of the legislation which he says “is already seen as a law of censorship”.

“It will only reinforce a sense of defiance towards the press and politicians who are already very discredited,” he warned.

Far-right leader Marine Le Pen, whose followers stand accused of spreading fake news, is among those who have spoken against the bill, asking: “Is France still a democracy if it muzzles its citizens?”

The EU, for its part, has said it does not want to create an Orwellian “Ministry of Truth” and will not legislate on fake news.

In France, there are also questions about how the law will work in practice.

Judges will have just 48 hours to rule on an urgent request to take down a report.

Legal expert Vincent Couronne says the law is “not only imperfect and unnecessary, but also dangerous for the peace and diversity of public debate”.

It will turn judges into “arbiters of true and false”, said Patrick Eveno, a media history professor at the Sorbonne university.

As for potentially kicking out foreign media, Fenoglio is deeply uncomfortable with the idea, not least given that Le Monde is blocked in China.

“I cannot defend measures under which it’s considered normal to block all kinds of information because it’s considered close to a foreign government,” he said.

yogaesoteric

June 26, 2018