How opium’s dark history explains today’s prescription drug crisis

There are rumours that swirl in the writing world: all the publishing houses of the UK now have teams dedicated to seeking out and commissioning books that will feed into a national sense of guilt about the country’s history. I couldn’t guess what the next big remorse theme would be: the opium trade.

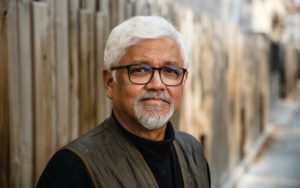

It was with a sense of foreboding that I opened Smoke and Ashes. I’m so glad I did read this superb book. The British Empire takes its beating – a just one – but its role is not as the masterful dark overlord, more a useful villain in a serious play about human weakness and arrogance in the face of inanimate forces.

The book analyses the effect of the opium trade on Britain, India, China and beyond. I expected it to focus on a discrete historical period, but the power of the story comes from following falling dominos that reach to current challenges. The historic trade is the lens that allows us to see the birth of a global narcotic monster, one that rears its head every time we drop our guard, most recently in the prescription opioid crisis.

There are so many surprising major and minor consequences to the trade, from battles to bureaucracy. Poppy cultivation led to a famine in Bengal in 1770 that caused the death of 10 million people and instigated tensions and conflicts that have never settled. “Almost all Asiatic wars have a strong narco-character through to the present,” writes Ghosh. Both the UK and Indian civil service exams are rooted in the East India Company’s, which were inspired by their traders’ observations of the Chinese system in Canton.

Ghosh knows our soft parts as a reader, he gives us big geopolitical stories – Mumbai, Singapore, Hong Kong and Shanghai were all initially sustained by opium – but only after we have been led by the nose through the factories. Indian workers were not only stripped, but also washed, to prevent them rubbing the opium over the body and then washing it off at the bazaar, “a method of pilferage that was said to fetch 4 annas [a quarter of a rupee] per washing.”

Under the grand sweep of history, there lies a simpler and scarier narrative. Ghosh shows how we repeatedly and lethally overlook our impotency on meeting poppy products:

“Morphine dependence came to be known as ‘morphinism’ or ‘soldier’s disease’, and the German pharmaceutical company Bayer Laboratories soon came up with a ‘cure’ that was touted as non-addictive, even though it was also an opioid. This was none other than heroin, the name of which was derived from the German for ‘heroic’.”

It is not far off a perfect non-fiction book; the writing is sublime, the research thorough, the eye for story superb and there are splashes of personal backstory that underscore the sincerity of the author’s arguments. Passages from his Ibis historical fiction trilogy (which began with 2008’s Booker-shortlisted Sea of Poppies) try to force their way in from the wings, but they are ushered off stage quickly and wisely.

The history of relations between powerful nations via the narrative of the opium trade, and centred in India, is utterly compelling. There is a twist in the tale, which blossoms into a core theme. We learn that neither the nations nor their leaders, armies or even merchants are the fascinating agents in this story of “the China trade”, as it was euphemistically known. The protagonist turns out to be the character of the opium itself and its omnipotent relationship with people. Opioids overpower people, because they are manipulating human weakness.

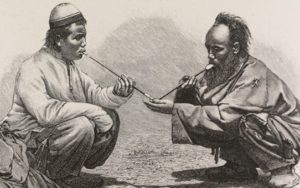

It is remarkable that the author conveys the power of opium without dwelling on the experience of the wretched users in China; we hardly meet them. He follows the available evidence, which is abundant in the labyrinthine bureaucracy of the East India Company, but scant amongst the fetid smoke on the far side of these trades.

There are so many strands to this story, all of them well handled. Some are sadly predictable, like greed, racism, sexism, bellicosity and addiction, but Ghosh brings brilliant facts and fresh treatment to each. White poppies were considered inherently better, despite evidence to the contrary. The Chinese were thought to be “‘effeminate’ by nature and hence more inclined to indulge in opium, which induced passivity.”

Serious scholarship is lightened regularly with enjoyable asides – the monkeys of Ghazipur drank from the drains of the opium factory and were said to be “the most contented and tranquil monkeys in all of Hindustan.” (The opium factory is still up and running, the monkeys probably not.)

The book gave me a deeper chill than any of the TV series about the opioid crisis I had viewed before reading it. It builds through many interwoven stories to its crescendo thesis: the poppy plant can be made into chemicals that will conquer humanity because they exploit our flaws at the individual, family, company, national and supranational level. The drugs capitalise on two of our most glaring vulnerabilities as a species, greed and addiction. The book scared me, because it reveals the drug to be so big, ugly and powerful as to make the British Empire seem its pawn. And it is very much an ongoing “multidimensional crisis”.

A key message is that demand is not really the issue, because opioids are too powerful a family of chemicals for that to be managed. They have “agency”, users don’t. If these drugs are available in almost any form, then the supply will engineer its own demand, often via the avarice of people, organisations or, indeed, an empire. Then they unleash mayhem. For all their wickedness, the bosses of Purdue Pharma weren’t idiots, they actually understood the basic truth that so many were blind to: a supply of opioids will create its own demand.

The most surprising passage comes near the end, where the author confesses that he found the whole opium story so bleak and hard to tell that he decided to abandon the book. This was not hyperbole or a passing thought – he cancelled his publishing contracts and returned the advances. The reasons he gives for returning to write it later on might be a little too idealistic and topical to be wholly convincing, but I am very grateful that he did, whatever the motivation. It is a brilliant book and worth reading without any big lessons, but we are going to need to heed the important ones on offer. Opium production is at an all-time high.

Author: Tristan Gooley

yogaesoteric

February 10, 2024