Hundreds of articles dismissing ‘conspiracy theories’ read like they follow a single script

“Now it’s conspiracy — they’ve made that something that should not even be entertained for a minute, that powerful people might get together and have a plan. Doesn’t happen. You’re a kook! You’re a conspiracy buff!” — George Carlin

“I don’t believe in conspiracy theories, except the ones that are true or involve dentists.” — Michael Moore

It’s not so much shooting the messenger as it is making everyone think the messenger is crazy and his or her message is automatically false. And crazy. And dangerous.

That’s the apparent goal of hundreds of mainstream articles, produced year after year, that denounce “conspiracy theories” and go to extreme lengths to discredit anyone who dares challenge the official narrative of any event. Points of view that venture outside of permissible boundaries are dismissed as the products of unbalanced minds.

Challenges are written off as being “bizarre,” “outlandish,” “pernicious,” or any one of a host of other exaggerated descriptors that reveal extreme bias. We’re told that the theories in question are false and that they were debunked years ago, as if making the claim is enough — no evidence required. What is offered as evidence usually comes in the form of quotes from some academic or other who is said to be an “expert” in the “psychology of conspiracy theories.”

The bylines on these propaganda pieces may change but the message doesn’t, as variations on the same article are endlessly regurgitated in a large number of publications. The “journalists” who create them appear to be working from a common template. And by this I don’t just mean they share a point of view; I mean they use the same dishonest points and tone.

The articles are too numerous, too similar, and too cartoonishly one-sided not to be intentional propaganda.

The stakes appear to be getting higher with each passing year. Where “conspiracy theorists” were once simply dismissed with condescending mockery, they are now being called “dangerous.” The alleged threats posed by their thoughts and words must now be combatted and stamped out to protect our “security.”

Censorship for security?

The establishment tells us that this supposed crisis of misinformation and disinformation must be dealt with by restricting what people say — and even ostracizing and shunning those who dare question official orthodoxy. The result in recent years has been a horrifying frenzy of censorship on the internet and anywhere that public discourse takes place.

After 9/11 it was the scourge of international terrorism that we were told we must fear. Now, in addition to pandemics and Russia (everything old is new again…), it is words that are dangerous and free speech that is a threat to us all.

“Suggesting that these cookie-cutter hit pieces are part of a coordinated propaganda campaign risks reinforcing the very message of that campaign. Make such a suggestion and you will be dismissed, ridiculed, and labeled a conspiracy theorist.”

Of course, suggesting that these cookie-cutter hit pieces are part of a coordinated propaganda campaign risks reinforcing the very message of that campaign. Make such a suggestion and you will be dismissed, ridiculed, and labeled a conspiracy theorist.

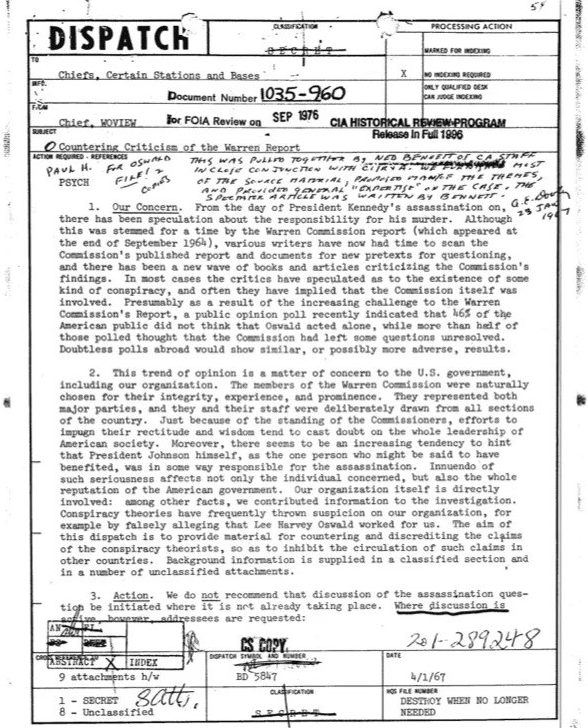

But there is a firm basis for suggesting that this is the product an intelligence operation, given that the CIA launched just such a campaign in 1967 when it distributed dispatch #1035-960 to its “assets” in the media (by this I mean journalists who were also on the payroll of the CIA). It urged these fake journalists to use certain tactics to discredit critics of the Warren Commission, which had concluded that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated by a lone gunman named Lee Harvey Oswald.

Critiques of the official position were dismissed as “conspiracy theories,” and Warren Commission critics were accused of being biased, out for personal gain, and possibly disloyal to the country

The CIA dispatch only became public in 1976 following a Freedom of Information Act request by the New York Times. On the dispatch were marked “PSYCH” (for psychological warfare) and “destroy when no longer needed.” The subject line read: “Countering Criticism of the Warren Report.”

In his book Conspiracy Theory in America, Lance DeHaven-Smith posits that the JFK assassination is the “Rosetta Stone” for understanding the origins of the conspiracy theory meme. He writes:

“The conspiracy theory label took form and gained meaning over a period of several years (or longer) in the context of efforts by the CIA, one of the world’s leading experts in psychological warfare, to deflect accusations that officials at the highest levels of the American government were complicit in Kennedy’s murder. … The CIA’s campaign to popularize the term ‘conspiracy theory’ and make conspiracy belief a target of ridicule and hostility must be credited, unfortunately, with being one of the most successful propaganda initiatives of all time.”

DeHaven-Smith notes that those who mock conspiracy theories out of hand “lump together a hodgepodge of speculations about government intrigue, declare them all ‘conspiracy theories,’ and then, on the basis of the most improbable claims among them, argue that any and all unsubstantiated suspicions of elite political crimes are far-fetched fantasies destructive of public trust.”

Many of the tactics outlined in the CIA dispatch show up in articles today blaming “crazy” conspiracy theories for threatening the very fabric of democracy. Of course, it is important to point out that just because a journalist writes one of these propaganda pieces does not mean he or she is knowingly part of an intelligence operation. The writer could be trying to conform to what an editor is demanding. Having said that, the pieces in question are propaganda either way.

“Many of the tactics outlined in the CIA dispatch show up in articles today about how ‘crazy’ conspiracy theories are threatening the very fabric of democracy.”

In his 2008 essay “See No Evil,” David Cogswell writes, “Conspiracy theories are not about conspiracies, they are about forbidden thought. The label ‘conspiracy theory’ is a stop sign on the avenues of rational thought and inquiry. It says, ‘Stop here. Entrance forbidden.’”

Evidence is made to seem irrelevant. We have tons of evidence that the 9/11 official story is a monumental lie (made up of thousands of smaller lies), but that has not stopped the propagandists from writing off 9/11 Truth as just one more “bizarre” theory. The focus in these articles is not so much on whether a conspiracy happened but on why someone would think that.

Essentially, it’s about crushing dissent. And it works.

“Credible” conspiracies — like Watergate and Iran-Contra — are acknowledged because they have been reported on by the corporate media. Anything that hasn’t received this seal of approval, it is argued, must not have happened.

This is exactly what Canadian journalist Jonathan Kay asserted in an interview I did with him in 2011 for my blog, Truth and Shadows. Kay, the author of Among the Truthers: A Journey Through America’s Growing Conspiracist Underground, explained that if 9/11 were really an “inside job” there would have been hundreds of ambitious reporters tripping over each other to get the story first.

In the book, Kay profiles “conspiracists” who were once at the top of their fields, like David Ray Griffin (professor of the philosophy of religion and theology) and Barrie Zwicker (journalist). Kay argues that high-achieving people like Griffin and Zwicker need something after retirement to keep their brains busy.

Here’s how he put it:

“… I think these people are motivated by a desire to solve puzzles. The puzzle-solvers, as I describe it in the book, are hyper-intelligent people who often come to their conspiracy theories late in life when they’re retired from a very intellectually demanding job and they no longer have this very taxing intellectual job to occupy their mind, and then they use all this intellectual firepower for chasing ghosts on the Internet and stuff… And a lot of these guys become prisoners of these obsessions. In some cases they become Shakespeare conspiracy theorists or 9/11 or they become birthers.”

I guess it’s the curse of being too smart to be satisfied with lawn bowling, looking at pictures of the grand kids, and sitting on a swing on the front porch sipping lemonade. (“I’m simply too smart not to be discovering all sorts of nefarious stuff that might be going on!”)

Of course, there are dozens and dozens and dozens of examples of proven conspiracies and deceptions — some leading directly to wars — that have been entirely or at least largely ignored by the media. Even when one or another of these is mentioned, it is often dishonestly or without the context needed to understand its importance. Worse still, the occasional appearance of a conspiracy in mainstream journalism is treated as evidence that there has been no effort made to suppress it. (“If you’ve heard of Operation Northwoods, that’s proof the system works!”)

Thought control tactics

These articles often begin with some supposed horror story about how a “conspiracy theory” has led to terrible consequences of some kind. (“My father was such a nice man until he started unraveling over loony beliefs that powerful people get together and do things for their own benefit without telling everyone! It’s like he joined a cult!”)

These consequences can be bad for democracy, it is claimed. Or they can be downright dangerous, such as when people try to claim that they should decide what does and doesn’t go into their own bodies. (“Once you start letting everyone make THOSE decisions, it’s bedlam!”)

What is really revealing is how much these propaganda pieces have in common over the past two decades as well as how they have evolved into something more ominous.

The articles take as a given that “conspiracy theories” are so self-evidently wrong that it’s unnecessary to even say why. “Crazy” theories about 9/11 — such as the Twin Towers being demolished with explosives — are labeled “false” or “debunked years ago,” as if saying this is enough to settle the question. (“Oh, you want EVIDENCE? Sounds like you’re one of those conspiracy kooks, too! Also, we gave you the evidence years ago. If you missed it, that’s your problem.”)

Authors will inevitably go into a pseudo-psychological accounting of why conspiracy theorists think the crazy things they do. And why they continue to do so even after having been shown, supposedly, the error of their ways.

Areas of conspiracy research for which a large body of evidence does exist are lumped in with ones the reader will find easy to laugh at. (“These people believe the craziest things: Elvis is still alive, Obama is from Mars, 9/11 was an inside job…”)

Of all the tactics used, the most important, I would argue, is the notion that there is something aberrant in the psychological makeup of someone who suspects that those who wield significant power might actually be up to something. A crazy notion to be sure.

From “Why Rational People Buy Into Conspiracy Theories,” The New York Times Magazine, May 21, 2013.

Apparently, those who challenge any official narrative do so because they have psychological hang-ups that leave them searching for answers outside the realm of reality. They are terrified by the notion that bad things randomly happen and must imagine some elaborate plot to account for these disturbing events.

In reality, the notion that government officials might participate in a plot to kill their own citizens, and get away with it, is far more terrifying than the notion than bad things randomly happen. Truth be told, the group that should be studied is the one that dismisses such ideas without even looking at the merits of the case.

Below, I list what I see as the most common recurring tactics of psychological manipulation that these articles inevitably contain. (Not every article contains all of the points listed below, but they almost always contain several of them.) There are some tactics that are so obvious I feel they go without saying. These include the extreme bias of the articles in question, the labeling of anyone challenging any official narrative as a “conspiracy theorist” (which makes no sense when applied to 9/11 since we already know that was a conspiracy by someone), and a snarky, condescending tone. Beyond those givens, here is my list of the characteristics that come up over and over and over.

- Assert that something in a person’s psychology makes them believe in conspiracy theories: This is the claim that people embrace conspiracy theories to help themselves make sense of a chaotic world by imagining that strings are being pulled to influence events.

- Claim that conspiracy theorists are paranoid, irrational, and anti-science: They can never be convinced they are wrong, we’re told, and they accuse their critics of being part of the cover-up.

- Maintain that conspiracy theorists don’t have evidence for their theories and they don’t care about what the facts say. They just “believe” they are right even after their claims have been “disproven”: This includes the claim that conspiracy theorists often believe contradictory things.

- Make bald assertions about “conspiracy theories” that are completely unsupported or just attributed to some academic who studies the “psychology” of conspiracy theories: Two excerpts from an article on the Student Voice website illustrate this. “Brendan Nyhan, a professor at Dartmouth, explains that liberals have become more vulnerable to fake news and conspiracy theories that favor their own worldview. It’s a known pattern; losing political control is directly correlated with an increased vulnerability to misinformation.” And: “The trouble with refuting that conspiracy, like all theories, is a refusal to accept opposing arguments, leading to even more denial, frustration, and exasperated defeat. Using qualitative evidence, in fact, can lead to even firmer views.”

- Use the term “conspiracist”: Conspiracist is a label that is intended to seem academic and authoritative but is really just dismissive. I found it used as far back as 2006, but I’m sure it was around well before that. In his 2011 book, Jonathan Kay made liberal use of the term.

- Attack “theories” using extreme and cartoonish descriptors (bizarre, pernicious, hooey, bogeyman): Remember, it’s all about cutting off inquiry before it even starts. Words are chosen not for their accuracy or appropriateness but to discredit and to prevent evidence from being considered. It’s not enough to claim that a given theory is “wrong,” it must also be “bizarre.” We hear about “nefarious” and “sinister” plots, and “shadowy” conspirators.

- Impugn the motives of conspiracy theorists: It’s often taken as a given that “conspiracy theorists” are pushing theories that they know are false. No evidence is ever produced to support this charge of lying. They are also accused of being in it only for the money. Conspiracy theories are not advocated for, they are “peddled.”

- Paint conspiracy theorists as fringe and/or “far right” and/or Trump supporters: This is self-explanatory marginalizing that is nothing more than a guilt-by-association tactic.

- Question why these “beliefs” persist after so many years: The assumption inherent in this question is that those who falsely believe in conspiracies should eventually come to their senses and see the error of their ways. The fact that theories (like “9/11 was an inside job”) continue to be advanced more than two decades after the event is offered as proof that those who hold the theories are influenced by something other than evidence and facts. The reality is that the evidence demonstrating that the 9/11 official story is false has only become more conclusive with the passage of time.

- State as if it’s a fact that certain theories are false and were debunked years ago: This is what is known as a bald assertion. No evidence need be provided to substantiate this claim. The idea is to con the reader into thinking the proof of its validity has been provided many times.

- Lump strong, or at least plausible, theories with weak or easily discredited ones (or at least with theories that are perceived as having been discredited): This is a form of guilt by association. The sudden and very suspicious resurgence of the flat Earth theory around 2016 offers a convenient way of dismissing evidence of crimes by the elite.

- “Debunk” the weakest or least credible points in “conspiracy theories”: This could include something like the claim that beams fired from space destroyed the Twin Towers is used to discredit any challenge to the official position that the buildings were brought down by plane impacts and fires alone.

- Make a theory sound false by giving a bogus, unfounded, or incomplete reason the conspirators would have engaged in the conspiracy.

- Dismiss any notion of government conspiracy on the grounds that government is much too incompetent to have been responsible for planning and executing a complicated event like 9/11: When governments are a little too enthusiastic about admitting they screwed up, it probably means they want to hide what they really did. The Iraq War and 9/11 are obvious examples.

- Begin articles by relating some supposed horror story where belief in one or more “conspiracy theories” by a person or group allegedly caused real harm.

- State that conspiracy theories are “dangerous” to democracy and to human health: Conspiracy theories must not just be dismissed, they must be combatted. If they are not, it is argued, catastrophic harm will be caused.

- Equate conspiracy theories with contagions: We regularly hear about the “spread” of conspiracy theories, a term that is bound to resonate with those who most fear the spread of actual viruses. One writer even likened these theories to sexually transmitted diseases.

- Link an explosion of conspiracy theories to the internet: This connection points to the supposed dangers of a free internet. It feeds into the idea that “misinformation” must be eliminated from the internet using censorship. This item also reinforces the myth that conspiracy theories are getting much “worse.”

These tactics are so “unjournalistic,” so unprofessional, that it is hard to understand how they can pass for legitimate journalism in publications like the New York Times, the Washington Post, Newsweek, The Wall Street Journal and so many others. It appears that the public has become so conditioned by this deluge of endlessly repetitive propaganda that we don’t even recognize it as such.

Author: Craig McKee

yogaesoteric

October 26, 2022