Mergers and Consciousness Games: From Media Consolidation to Digital Indoctrination

By the time I studied broadcasting and journalism in the mid-1960s, newspaper sales were already dropping, even though people were being more, if not better educated. Local newspaper competition had disappeared in most major cities. Between 1965 and 1980, mass media in the US came under greater control by national and multinational corporations. As Ben Bagdikian noted in The Media Monopoly, distant ownership need not have alienated readers. But corporate owners also “changed the form and content, the strategies of operation, and the economics of newspapers.”

Pressure to maximize profits increased as huge parent companies competed for investments and higher dividends in international markets. This hastened the conversion of newspapers into primarily carriers of advertising, and eventually led to deep staff cuts.

In those days, Walter Cronkite was known as the most trusted man in America.

That is, if you believed Reader’s Digest, which provided a glimpse behind the curtain in June 1980. “We have to set ourselves up as judges of the news,” Cronkite proudly told the Digest. “A good journalist doesn’t just know the public, he is the public.” It was a monument of self-righteous entitlement.

His pretense of identification with the masses masked Cronkite’s role as the ultimate “insider” mouthpiece, one who often reflected the consensus of the electronic establishment. In 1980, for example, when he noted every night how many days Americans had been held hostage in Tehran, it wasn’t just because he and The People felt strongly. It was corporate policy at CBS.

At the time CBS was in the top five of about 50 corporations that controlled most daily newspapers, magazines, television stations, publishing houses, and major movie companies; in short, the pre-digital media-scape. By the end of the 1980s, that 50 corporations was reduced by at least half, some of them more dominant in a specific medium. But the highest levels of world finance had become intertwined with the highest levels of media ownership, which produced greater control over the systems on which the public depended for news and information.

At the top of the list were Capital Cities, which had absorbed ABC; Cox Media, then a newspaper powerhouse; CBS; Disney; Gannett; General Electric; Paramount; Harcourt Brace; and Bertelsmann. Old empires like Hearst and Knight Ridder had begun to fall. New empires like Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. were beginning to rise.

By the time Ronald Reagan became president and Bernie Sanders was Burlington’s mayor, the Gannett Corporation owned over 90 daily newspapers and USA Today, plus dozens of TV and radio stations.

One of those newspapers was the Burlington Free Press, Burlington’s only daily, which dominated local print in my hometown until the rise of alternative weeklies. At the time Gannett was positioning itself to combine print, data and the emerging video market. But its vision and influence were dwarfed by News Corp., which not only acquired newspapers, 20th Century Fox and its archives, but also TV Guide and the Annenberg empire.

An equally awesome merger was that of Time. Inc. and Warner Communications. Then Time-Warner merged with America Online, the leading Internet company at the turn of the century. This $350 billion deal set off speculation that the world’s largest media and entertainment entity could revolutionize communication. The forecasters were at least partly right.

By the end of the 20th century, consolidation had boiled down major media ownership to less than ten corporations at the top. Legacy giants General Electric, Disney and Bertelsmann maintained their spots, joined by News Corp., Time Warner, Viacom, Sony, AT&T, and Seagram. Together they owned most of the world’s TV stations, newspapers, magazines, and recording and film companies. Broadcast and cable channels were multiplying, but this obscured the increasingly centralized ownership.

Take General Electric, which owned NBC and its cable division. It also had investments in Bravo, AMC and the Independent Film Channel (IFC), and was a partner in the PrimeStar satellite system.

A prime example of the consolidation process involved CBS, Paramount, Viacom, and MCA, one of the giants purchased during the 1990s by the Japanese and Gulf + Western, which listed Paramount Pictures and Simon & Schuster among its holdings. In 1989, G+W changed its name to Paramount Communications and shed its non-media businesses. The idea was to concentrate on the global communications race. But Viacom stepped in. Already owner of movie houses, Blockbuster, Spelling Entertainment, and networks like Showtime, Comedy Central, MTV, VH-1, USA, Lifetime and Nickelodeon, Viacom bought Paramount for $10.4 billion. In May 2000, it merged with CBS, a $45 billion deal that involved 38 TV stations, 162 radio stations, movie studios, publishers, theme parks, and more. Meanwhile, MCA merged with WorldCom and paid $122 billion for Sprint.

Before the emergence of the Internet, the most dynamic sector of broadcasting was the expansion of cable television. In 1980, less than 15 million homes were “wired.” Within ten years, the number jumped to 54 million subscribers, almost two thirds of all homes with TV sets. But aside from C-SPAN and CNN’s war coverage, the proliferation of channels mainly brought more of the same — TV reruns, home shopping, movie channels, televangelism, and commercials posing as programs.

By 1998, there were already 120 million Internet users, and it was obvious that digital media would transform mass communications. At first it reached only a few percent of the world’s population, and took about a decade to become truly global. But as the “information superhighway” was built, the same corporations began to vie for access to this enormous new market.

In 2006, The Nation’s periodic review of what it called “the national entertainment state” listed just six top members — Disney (including ABC), CBS, General Electric (NBC), News Corp. (Fox), Time Warner (CNN), and Viacom (Paramount, MTV, and Dreamworks).

But consolidation still continued. In 2016, Comcast merged with GE.

Two years later, AT&T absorbed Time Warner for more than $85 billion, as Viacom lost ground under the aging mogul Sumner Redstone. In terms of global advertising, the list differed a bit. Google was number one, followed by Comcast, Fox, and Facebook.

By 2023, the big six movie studios were down to just two — Disney and Netflix. But due to streaming services, combined with the decline of cable and major film studios, these two faced competition in a landscape increasingly dominated by Apple and Amazon. “These behemoths have the corporate muscle to influence not just what gets made but also how it gets distributed and marketed even how (or whether) it gets reviewed,” The Nation concluded.

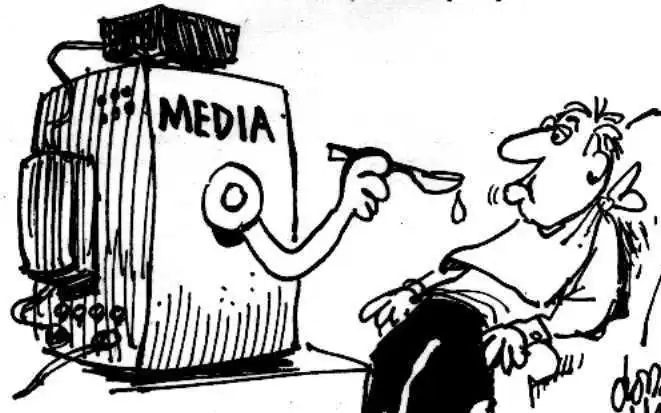

Today information comes to us faster, and at greater volume, than ever before in human history. But from the telegraph to television, and on to the Internet, mass communication has long been a double-edged sword, especially when it comes to what is true.

In the current era, as facts have been greatly devalued, it has become more difficult to tell the difference between truth and opinion, and also between unintentional errors (misinformation) and purposeful lies (disinformation).

There are so many possibilities, yet reliable standards of proof are hard to find. Theories evolve, expand and mutate rapidly in unexpected ways as they circulate through cyberspace. Speculation, conjecture or outright falsehoods become accepted as “true” with constant repetition.

Compounding the problem, search engines use algorithms to keep us engaged. Even without the additional manipulation of marketing and consultants who may influence listings, over time our searches are shaped to fit our profiles. Information is prioritized to reinforce previous choices, influenced by suggested assumptions and preferences. As Eli Pariser argued in The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You, environmental activists and energy executives get very different results when they inquire about climate science. It looks and feels “objective,” but they are mainly offered data that fits with their existing view – and not much that conflicts.

One study discussed in Sociological Quarterly looked at this by following attitudes about climate science over a decade. Although a consensus emerged among most scientists over the years, the number of Republicans who accepted their conclusion dropped. Why was that? Because the Republicans were getting different information than the Democrats and others who embraced the basic premise. In other words, their viewpoint was being reflected back at them.

Is reinforcement through search engines leading to inadvertent self-indoctrination? For democracy to function effectively, people need exposure to various viewpoints. “But instead we’re more and more enclosed in our own bubbles,” Pariser warned. Rather than agreeing on a set of shared facts we’re being led deeper into our different worlds.

Author: Greg Guma (historian and former CEO of Pacifica Radio)

yogaesoteric

January 16, 2024