“One Health” – Where Biosecurity Meets Agenda 2030

A blueprint for taking over food chains and natural areas in the name of public health

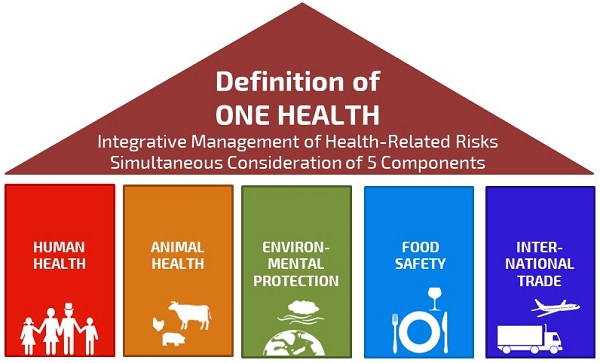

According to the UN and associated agencies, nature and food chains are sources of pathogens with pandemic potential. To protect citizens from them, the “One Health” approach has been developed: the UN, the CDC, EU, RIVM, universities, corporations, and NGOs are working together worldwide to monitor and anticipate potential risks by coordinating collaboration at local, regional, national and international levels.

Is this a blueprint for expanding power of the UN and WHO – allowing them not only to set health policy in the event of crisis, but also to take control of food chains and natural areas in the name of public health?

“‘One Health’ is an approach to designing and implementing programs, policies, legislation and research in which multiple sectors collaborate and exchange to improve public health,” is explained on the World Health Organization (WHO) website.

“Many of the same microbes that infect animals are harmful to humans, and they are part of the same ecosystems.”

According to the WHO, to combat these risks coordinated action between public health, animal health and environmental organizations is required. ‘One Health’ particularly focuses on risks to food safety, zoonoses – animal-to-human transmissible infections –, antimicrobial resistance, “and other risks to public health.” Livestock, in particular, is seen as a high-risk source of zoonoses.

One health: expanding biosecurity governance with Agenda 2030

It fits perfectly into what philosopher Giorgio Agamben calls the paradigm of biosecurity. In the article ‘Biosecurity and politics’, Agamben warns that the use of health terror is a means of governing through worst case scenarios. He explains that this is an entirely new model of governance: ‘the citizen no longer has the right to health, but is legally obliged to health’. Since few people adhere to political philosophies or ideologies anymore, security or health are the only reasons for which citizens allow far-reaching restrictions on their fundamental rights. Agamben: “the biosecurity governance model shows that it can flatten all political and social relations under the guise of civic participation.”

Judging from the activities that have been taking place in the last 10 years under the guise of ‘One Health’, this biosecurity is being extended under the radar to anything that can affect health. Starting with our food and nature. The ‘One Health Commission’ lists “some” areas that “urgently need to start applying the One Health approach, at all levels of academia, government, industry, policy and research, because of the indelible interconnectedness of animal, environmental, human, plant and planetary health:

• Agricultural production and land use

• Animals as Sentinels for Environmental agent and contaminants detection and response

• Antimicrobial resistance mitigation

• Biodiversity / Conservation Medicine

• Climate change and impacts of climate on health of animals, ecosystems, and humans

• Clinical medicine needs for interrelationship between the health professions

• Communications and outreach

• Comparative Medicine: commonality of diseases among people and animals such as cancer, obesity, and diabetes

• Disaster preparedness and response

• Disease surveillance, prevention and response, both infectious (zoonotic) and chronic / non-communicable diseases

• Economics / Complex Systems, Civil Society

• Environmental Health

• Food Safety and Security

• Global trade, commerce and security

• Human – Animal bond

• Natural Resources Conservation

• Occupational Health Risks

• Plant / Soil health

• Professional education and training of the Next Generation of One Health professionals

• Public policy and regulation

• Research, both basic and translational

• Vector-Borne Diseases

• Water Safety and Security

• Welfare / Well-being of animals, humans, ecosystems and planet”

One Health background and funding

The idea of “one world, one health” was first floated by the Wildlife Conservation Society at a conference in New York in 2004. Six unspecified ‘international organizations’ then developed a strategic framework that was presented at the International Conference on Avian and Swine Flu in Egypt in 2008. In the same year, the One Health Joint Steering Committee (OHJSC) and a One Health Commission (OHC) are established with the help of an unspecified “significant donation” from the Rockefeller Foundation.

The goal of the commission is to put One Health on the map worldwide. The Rockefeller Foundation launched the disease surveillance networks (DSN) initiative in 2007, with an initial investment of $22 million. A portion of this will likely have gone to the OHJSC, as the foundation reports: “Global disease surveillance networks are part of the One Health view of the world. The Rockefeller Foundation recognizes that the local and regional context is part of an international web of relationships, managing health issues requires regular diplomatic actions and trade space for technocrats.”

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is also committed to the One Health approach, it is one of five components of the ‘Grand Challenges’ program in which a total of $100 million has been invested. According to researcher Akio Yamada, these ‘donations’ show a shift in the focus of philanthropic institutions from single issue topics to intersectoral, multidisciplinary projects.

One Health at the EU, Netherlands and the US

Over the years, a veritable infrastructure for a coordinated intersectoral approach has been put in place – out of sight of the general public – at all possible levels of government.

Stella Kyriakides, the EU Commissioner for Health and Food Safety, emphasizes the importance of One Health in her speech at the G20 Summit on September 6, 2021: “‘One Health’ has been a priority within the EU for several years now. It is clear that we need to expand our knowledge on environmental conditions, and surveillance, detection and collective action on human-animal interaction. For a strong European health union, we call for the development of European and national preparedness plans so that we can better face future crisis.” We have learned in recent years that such ‘preparedness plans’ have great predictive value.

In 2019, the EU has established the European joint program (EJP) in which 44 laboratories and research centers in 19 member states are committed to knowledge development in the field of One Health and ware working on the establishment of a sustainable framework through which activities of medical, livestock, and food institutes are aligned and integrated. The Dutch University of Wageningen (WUR) is involved, and RIVM (the Dutch CDC) also plays a major role: it coordinated the development of a strategic agenda and participates in 20 of the 29 projects of the EJP. To support international cooperation the RIVM is “involved in partnerships with similar parties in other countries, and cooperates with the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the European Centre for Disease Control (ECDC).”

Wageningen is also involved in the Netherlands Centre for One Health (NCOH), an “open innovation network.” Not only the RIVM and Wageningen are active in putting One Health on the map in the Netherlands: “The Netherlands is particularly vulnerable when it comes to viral diseases, due to mosquitoes, and because of the high population density and intensity of livestock farming,” warns the Dutch research consortium One Health PACT, in which experts work together. The ‘One Health Portal’ supports “professionals from the human and veterinary domain.”

Outside the EU and in the Netherlands, the One Health approach is also falling on fertile soil in the US: The Centre of Disease Control, the US version of the RIVM, writes on its website: “One Health is gaining recognition in the US and worldwide as an effective way to address health problems caused by human-animal contact.” One Health is also part of the ‘National Biodefense Strategy’.

One Health at the UN level

The UN is putting the icing on the cake with the establishment of the ‘One Health High-Level Expert Panel’ (OHHLEP) in November 2020. According to the text on the website, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and WHO, led by Germany and France, took the initiative to establish the expert panel. On April 29, these UN organizations signed a “groundbreaking agreement to strengthen cooperation to sustainably balance and optimize the health of humans, animals, plants and the environment… The new Quadripartite MoU provides a legal and formal framework for the four organizations to tackle the challenges at the human, animal, plant and ecosystem interface using a more integrated and coordinated approach. This framework will also contribute to reinforce national and regional health systems and services”.

The same organizations – FAO, OIE and UNEP – were named in the proposal to amend the International Health Regulations (IHR) to be involved in declaring an international health crisis. It is interesting to note that in addition to including more UN agencies in combatting ‘health crises’, these changes proposed expanded surveillance capacity and the support of developing these capacities in countries where the infrastructure was lacking. Because Southern Hemisphere countries opposed these changes, they did not pass. However, it shows the way in which the WHO intends to expand its tentacles, and the negotiations on the pandemic treaty are still continuing.

Genomic surveillance

In March 2022, the WHO has published its “Global genomic surveillance strategy for pathogens with pandemic and epidemic potential, 2022-2032”, which applies genomics to track infectious diseases by sequencing the genomes of bacteria, parasites and viruses. The supporting documents give a lot of information about how wonderful genomic surveillance is for tracking of the development of diseases, but give surprisingly little information about what kind of samples are collected (blood, saliva, other?), from what sources, and in what databases they are stored.

However, John Hopkins, Nature and other publications have reported that “Covid-19 has created a ‘watershed’ moment for wastewater Surveillance”. In the article “Secretive HHS AI Platform to Predict US Covid-19 Outbreaks Weeks in Advance”, the research journalist Whitney Webb reports that smart sewer and robotic wastewater collection can also be commercialized to “not only offer insights on drug consumption or contagious disease outbreaks” but also information on community “eating habits” and “genetic tendencies” in order to “develop individual readings of particular neighborhoods”. Of course, the same samples – blood, sewage? – that are purported to track viruses and bacteria, store our DNA information. In the article “The War Over Genetic Privacy Is Just Beginning”, John W. Whitehead and Nisha Whitehead explain that using DNA, scientists are able to track salmon across hundreds of square miles of streams and rivers. With government, research, and ancestry databases with individual DNA profiles that abound, theoretically it is not only possible to match for viruses, but for people as well.

The EU project ‘Compare’, is seeking to expand this genomic surveillance under the banner of ‘One Health’. In it, 28 European partners work together to tends to “speed up the detection of, and response to disease outbreaks among humans and animals worldwide. This new approach to disease surveillance will be able to revolutionize the way we combat diseases globally.”

yogaesoteric

October 14, 2022