Paul Craig Roberts: Why do academics fear the truth about 9/11?

REASONS WHY IR SCHOLARS IGNORE 9/11 TRUTH

Given the substantial body of evidence indicating that the official 9/11 narrative is false, why has none of it appeared in the discipline of International Relations? There are three main reasons: (i) the weaponization of the term “conspiracy theory”; (ii) the taboo on questioning the ruling structures of society; and (iii) a neo-McCarthyite political climate.

The weaponization of “conspiracy theory”

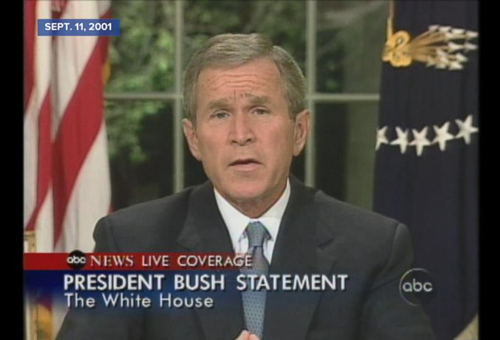

IR scholars, like other academics, appear to have taken their cue from President George W. Bush (2001): “Let us never tolerate outrageous conspiracy theories concerning the attacks of September the 11th.” The knee-jerk reaction to anyone questioning the official 9/11 narrative is to brand them a “conspiracy theorist,” and amazingly this is true even within academia. For example, consider the following reviewer comments I received on a manuscript submitted to a different journal:

“The 9/11 section is full of very dodgy information that does not stand up to even mild scrutiny. An example is the discussion of WTB7, where the author rehashes a famous discredited conspiracy theory. It is really no mystery why WTB7 collapsed (and why it was reported before the collapse). Hit by debris, and on fire for seven hours, it was eventually abandoned by firefighters, and subsequently collapsed.”

These words, which parrot the official narrative and resort instinctively to the “conspiracy theory” smear, were written after the publication of the Alaska, Fairbanks, study which concludes that “fire did not cause the collapse of WTC 7 on 9/11” (Hulsey et al., 2019: 2). Where is the science here and where the superstition?

As IR scholars really ought to know, the term “conspiracy theory” is weaponized. Though in use beforehand, it was systematically propagated by the CIA through the mainstream media from 1967 on in order to deflect accusations that officials at the highest levels of the American government were complicit in [President] Kennedy’s murder. […] The CIA’s campaign to popularize the term “conspiracy theory” and make conspiracy belief a target of ridicule and hostility must be credited, unfortunately, with being one of the most successful propaganda initiatives of all time. (de Haven-Smith, 2013: 25)

As Falk (2007: 120) points out, “this management of suspicion [through the “conspiracy theory” label] is itself suspicious.” To dismiss 9/11 truth as “conspiracy theory” is not only intellectually lazy, supercilious, and uninformed, it is also the hallmark of vulnerability to a longstanding psychological warfare operation. Such an approach is unbecoming of serious scholarship.

There exists an intellectual tradition in the United States of seeking to discredit anyone who takes seriously the possibility of high-level conspiracies in US politics. This goes back to Richard Hofstadter’s 1964 essay on the “paranoid style” of American politics (Hofstadter, 1965). Whilst “there is nothing paranoid about taking note” of real “conspiratorial acts in history,” Hofstadter argues one year after the JFK assassination, we should beware of conspiracy theories that “alert us to a distorted judgment” (1965: 29, 6). This tendency is not limited to “people with profoundly disturbed minds,” but also describes “modes of expression by more or less normal people” (Hofstadter, 1965: 4). With the unstated assumption being that real conspiratorial acts do not take place in the US political system, the implication is that any sane person who points to evidence of such acts must be “paranoid,” their judgment “distorted.”

That tradition became weaponized in 2009 when Harvard law professor Cass Sunstein, recently appointed as President Obama’s head of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, co-authored a paper advocating the use of anonymous government agents to engage in “cognitive infiltration of extremist groups, designed to introduce informational diversity into such groups and to expose indefensible conspiracy theories as such” (Sunstein and Vermeule, 2009: 205). 9/11 truth is the primary target of the paper. “Government agents (and their allies),” the authors propose, “might enter chat rooms, online social networks, or even real-space groups and attempt to undermine percolating conspiracy theories by raising doubts about their factual premises, causal logic, or implications for action, political or otherwise” (2009: 224).

Although the premises, logic, and implications of Sunstein and Vermeule’s paper are comprehensively refuted by Hagen (2011) and Griffin (2011), it is clear that there has been massive infiltration of the 9/11 truth movement by agents seeking to subvert it (see Johnson, 2011; 2017). “Interference in ongoing research,” writes Johnson (2011: 233), has led to “depression of the quality of discussion” and “seemingly temporary and permanent changes in the behaviour of those involved in 9/11 research.” The fracturing of the 9/11 truth movement is not accidental but, rather, the result of deliberate attempts to undermine it. Techniques used include seeding misinformation, ridiculing certain authors, promoting nonsense theories, and outright censorship (in the case of Dr. Judy Wood). Of course, if elements of the US government were complicit in 9/11, then pervasive efforts by “[US] government agents (and their allies)” (Sunstein and Vermeule, 2009: 244) to subvert the 9/11 truth movement make sense.

The power of taboo

Certain topics are deemed off limits for socio-political reasons. The basic principle is never to discuss anything that is in conflict with the ruling structure of society, and that principle is enforced by systematic exclusion of such topics from consideration in mainstream media and political discourse, such that all debate and discussion remains confined to a spectrum of acceptable opinion (McMurtry, 1988; Herman and Chomsky, 2010). A “spiral of silence” then sets in whereby individuals, consciously or unconsciously unwilling to fall outside the spectrum of acceptable opinion, never question it (Noelle-Neumann, 1993). In anthropological terms, Chomsky notes (2008: 177), “we are dealing here with a form of taboo, a deep-seated superstitious avoidance of some terrifying question […]”

The contemporary taboo is 9/11 truth and the terrifying question is how power really works in the United States. For if 9/11 truth were to be taken by influential arbiters of reality as accurate, as an increasing number of people here and abroad appear to believe, then it will exhibit the great vulnerability of American constitutionalism to fundamental subversion from within by the most extreme and ethically depraved members of its own political community. (Falk, 2007: 122)

The possibility that the US political system, a self-proclaimed beacon of democracy, has been hijacked by psychopaths and war criminals is not something that most people are willing to entertain. “The conclusions [about US complicity in the attacks] are difficult to accept,” Chossudovsky recognizes, “because they point to the criminalization of the upper echelons of the State. They also confirm the complicity of the corporate media in upholding the legitimacy of the Administration’s war agenda and camouflaging US sponsored war crimes” (2005, xxi).

The “establishment-left,” to borrow MacGregor’s (2006: 194) apt term, shrinks from recognizing any possibility of US government involvement in 9/11. It includes such figures as Mary Kaldor, Samir Amin, Michael Parenti, Michael Mann, Charles Tilly, Tom Nairn, Susie Orbach, and Stephen Lukes, as well as “an array of left-wing and liberal journals and websites, from Counterpunch to The Nation and from Socialist Register to The New Left Review” (MacGregor, 2006: 193-6). The establishment-left typically interprets 9/11 as “blowback,” i.e. a predictable response by the disenfranchised and underprivileged of the world to US-led globalization, the oppressed periphery striking back against the imperial core. It is hard to argue with MacGregor’s assessment that the establishment-left is “out of touch with the historical realities of terrorism,” failing to recognize the “most virulent source of terror, the state [itself]” (2006: 199).

Psychologically, 9/11 truth can generate a sense of ontological insecurity as those waking up to it realise that key propositions that they have been socialized to accept are false. As one US academic writes, questioning the official 9/11 narrative means that “everything changes.” Possible changes include: loss of belief and trust in government; loss of belief in the value of democratic participation; loss of belief in my own tradition as a bearer of ‘civilization’; loss of belief in the power of dialogue and compromise as a basis of civil society; loss of belief in openness and transparency in public policy; loss of faith in my democratically elected government to act on values and principles compatible with my own, etc. (Smith, 2012: 348) As the language of loss indicates, this is a lot for anyone to come to terms with, and too much for many Westerners to deal with, at least to begin with.

Neo-McCarthyism

There is a longstanding connection between US wars and the suppression of academic freedom: All too frequently a call to arms abroad against the latest threat to American hegemony has a domestic battleground as well. From World War I to the nationalistic excesses following the September 11 attacks, public and private entities have tried to purge free speech from the academy without which the pursuit of truth would be futile. (Kirstein, 2009: 70)

After 9/11, governments in the US, Britain, and elsewhere “legislated extremely rigorous limits on dissent regarding the War on Terror” (MacGregor, 2006: 195). Academic silence on 9/11 truth can, accordingly, be attributed to “the disciplining effect of the War on Terror and the state of emergency, which […] is even stronger than McCarthy-era anti-communism” (van der Pijl, 2014: 229). The neo-McCarthyite climate of fear and intimidation that descended over academia after 9/11 has “greatly impeded the acceptance and publication of research papers that question or contradict the official account of that event” (Wyndham, 2017: 3).

Academics are faced with clear disincentives when it comes to speaking out on 9/11.

For example, when William Woodward, a psychology professor at the University of New Hampshire, expressed his view that the Bush administration allowed 9/11 to occur in 2006, students and state legislators call for him to be fired. The same thing happened to Kevin Barrett, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor who believed that the Bush administration had orchestrated 9/11 in order to justify military operations in Iraq (Rosborough, 2009: 565-6). Professor Steven E. Jones, an influential name in 9/11 truth, was allegedly edged into retirement by Brigham Young University in 2006. Dr. Judy Wood left Clemson University in 2006 for reasons that remain unclear, but it appears that her 9/11 research was incompatible with holding an academic post. Dr. Daniele Ganser was dismissed by ETH Zurich in 2006 for “spreading nonsense conspiracy theories” about 9/11, to quote his erstwhile line manager, Professor Kurt Spillmann (cited in Schawinski, 2081: 41). When Morgan Reynolds raised evidence-based doubts about the official narrative in 2007, he was singled out for censure by University of Texas at Austin President and former CIA director Robert Gates (Reynolds, 2007).

The pressure on academics to lose their jobs for speaking out about 9/11 has been mirrored in other sectors. Kevin Ryan, a former site manager at Underwriters Laboratories (which certified the WTC steel), was fired in 2004 after publicly challenging the official claim that “jet fuel” caused the destruction of the Twin Towers. Cate Jenkins was dismissed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2010 after speaking out about the agency’s role in covering up the levels of toxicity in the World Trade Centre dust. When a federal court ruled that Jenkins had been unfairly dismissed and ordered the EPA to reinstate her with back pay, the EPA kept her on paid administrative leave and refiled the same charges against her in 2013 (Corbett, 2019). Michael Springmann, who blew the whistle on the role of the Jeddah consulate in supplying US visas to terrorists, suddenly found, in his own words, that he “couldn’t get a job anywhere” (cited in Corbett, 2019).

Whilst the disincentives against 9/11 truth are great, so too are the incentives to toe the official line. Falk (2007: 127) sums it up: “Never before has it been as imperative to struggle for a true rendering of the 9/11 reality, and never have the incentives been greater to prevent such a rendering.” For example, explosives expert Van Romero, who changed his tune from “explosives devices inside the buildings […] caused the towers to collapse” to “certainly the fire is what caused the building to fail” went on to win $15 million of federal research funding (Reynolds, 2007: 112).

Sceptics sometimes question why there are so few academic journal articles on 9/11 truth, as though knowledge could only be genuine if stamped with the imprimatur of peer-review. But when the institutional environment of academia is so hostile to 9/11 truth – for political rather than intellectual reasons – then the paucity of peer-reviewed scientific literature on the events of 9/11 comes as no surprise: As 9/11 research has shown in perhaps magnified form, the formal peer review process can be used as a weapon to bury opposing views and stifle independent research whose natural conclusions are in opposition to established or official narratives and vested interests. The tendency to look down upon or disparage a paper that has not gone through or survived the formal peer review process is widespread but often unwarranted (Wyndham, 2017: 6).

Indeed, it is certainly true that some extremely important 9/11 research exists in non-peer-reviewed format. To the extent that the peer review system has worked to stifle 9/11 truth, as Wyndham alleges, it even stands to reason that some of the most important 9/11 research may not have been peer-reviewed.

Universities, the supposed guardians of legitimate knowledge, remain the one place where research into the events of 9/11 is generally forbidden. No doubt such research would displease corporate and state funders, as well as the sizeable portion of students, staff, and the general public who, having never independently investigated the events of 9/11, uncritically accept the official narrative. Contrary to ideas about academic freedom, the reality has been that barely a word threatening official orthodoxy on 9/11 may be uttered in academia. Those academics who have spoken out have tended to be emeritus or retired professors with little to lose career-wise, e.g. David Ray Griffin, Peter Dale Scott, Morgan Reynolds, Graeme MacQueen, Richard Falk, Robert Korol, Eric Larsen, John McMurtry, and Kees van der Pijl.

Van der Pijl found himself on the receiving end of the new McCarthyism in 2019, when he resigned his emeritus status at Sussex University after the university threatened to withdraw it because of a tweet in which he alleged Mossad involvement in 9/11. He accompanied his decision with a full-length academic paper providing supporting evidence for his claim, noting that criticism of the state of Israel does not equate to anti-Semitism and claiming that the university’s attempt to censor him amounts to an attack on free speech and academic freedom (van der Pijl, 2019). Whatever one thinks about van der Pijl’s views on 9/11, the latter points are surely valid.

Dr. Piers Robinson was attacked by the Huffington Post in 2018 for suggesting that the 9/11 Consensus panel findings present “a serious challenge for mainstream academics and journalists to start to ask substantial questions about 9/11” (York, 2018). Eight months earlier, the Times had tacitly called for Robinson and his colleagues in the Syria Media Propaganda Working Group to be fired, comparing them to holocaust deniers that a history department would not employ (Keate, Kennedy, Shveda, and Haynes, 2018). In April 2019 the Sheffield University student newspaper The Forge alleged Robinson was “engaging in denial” of anti-Semitism allegations within the Labour Party after he signed a petition saying it was “being used as a weapon to silence those who speak out against injustice.” Academics who dare to challenge official narratives can, it seems, expect to find themselves subjected to a media smear campaign as part of a coordinated effort to discredit them.

Conclusion

There is something sinister about the refusal of academics to subject the events of 9/11 to critical examination. While a sizeable and growing proportion of the world’s population has long had doubts about the official 9/11 narrative,* academia has maintained a rigorous regime of self-censorship. Nowhere is that more true than in the discipline of International Relations, where the official narrative on 9/11 is accepted virtually without question.

Although IR scholars are meant to be trained experts in such phenomena as false flag terrorism, there is a sense in which they might be forgiven for not exploring the possibility that 9/11 was a false flag in the immediate years after the event. After all, 9/11 truth did not begin to gain traction until around 2005-2007, when Griffin (2005) discredited The 9/11 Commission Report, organizations such as Scholars for 9/11 Truth (2005), Pilots For 9/11 Truth (2006), and Architects and Engineers for 9/11 Truth (2006) were founded, and Dr. Judy Wood and Dr. Morgan Reynolds brought Qui Tam cases (2007) against Applied Research Associates and Science Applications International Corporation for their allegedly fraudulent role in the production of the NIST reports. However, the longer that time goes on, and more people around the world come to understand that there is something deeply suspect about the events of 9/11, the more inexcusable it becomes for academics to continue to turn a blind eye to those events. The burden of proof today is on academia to defend the official narrative against the allegations that have been made against it. This requires engaging with 9/11 truth rather than ignoring it.

Should academics prove unable to defend the official narrative, several major consequences would follow. First, the possibility that 9/11 was a false flag would have to be taken seriously. “What the 9/11 attacks showed more than anything,” writes Hastings Dunn (2013: 1243), “was a willingness on the part of the perpetrators to think creatively and to employ technologies and tactics that were entirely unconventional in order to achieve strategic surprise, shock and destruction.” Absolutely, but who were the perpetrators and what technologies were involved? What kind of technology, for example, can turn a 110-story steel-framed skyscraper mostly into dust in a little over ten seconds, and who would have had access to such technology?

Second, an inability to defend the official narrative would necessitate reflection on why that narrative has for so long been uncritically accepted among scholars who pride themselves on their ability to think critically. Certainly they should not be taken in by far-fetched conspiracy theories such as the one put forward by the Bush administration. A certain humility would be required in order to recognise that so-called “conspiracy theorists,” often without academic credentials, have done far more to uncover the truth about 9/11 than academia. In that respect, academia would stand deeply discredited.

Pedagogically, far greater attention must be paid to false flag terrorism, in particular as perpetrated by Western states. For if, as increasing numbers of people are claiming, 9/11 was a false flag operation, then this is something that needs to be exposed. And if false flag operations can have the kind of impact upon society that 9/11 had, then clearly these kinds of operations need to be studied far more. They should be the subject of extensive public debate, and leading figures from various disciplines need to apply their expertise to studying and analyzing these events. Only by subjecting them to such attention will we put an end to these appalling crimes (Everett, 2008: 387).

One implication of this is that “Critical Terrorism Studies” can no longer play down the use of false flag terrorism by Western states. After all, if IR’s failure to foresee the end of the Soviet Union led to a decade of soul searching, how much worse would be missing false flag terrorism on 9/11?

If 9/11 was a false flag event, then academics have been complicit in maintaining the pretence that it was not. By extension, they are complicit in the horrific consequences that have flowed from 9/11, because they have failed to challenge the Great Lie on which everything was based. Admittedly, remarks MacQueen, “It takes a certain intellectual courage to question a story that is being promoted so heavily by virtually every government in the world, as well as the mainstream media” (see Zuberi, 2013). Yet, there is a moral imperative to tell the truth when so much murder and suffering is based on lies. As George Orwell is reputed to have said, in a time of universal deceit telling the truth is a revolutionary act.

Let us assume for a moment that the only Muslims involved in perpetrating 9/11 were patsies – which is reasonable based on the evidence – and that 9/11 was blamed on Muslims in order to legitimize US military interference in a string of Muslim-majority countries. What would this imply about the discipline of International Relations? “By selling out to the self-fulfilling fiction of Islamic terrorism,” claims van der Pijl (2014: 189, 229), “the discipline of IR today has itself largely degenerated into a mercenary, ‘embedded’ auxiliary force” – a process that has been catalyzed by foundation funding flowing to research on “Islam,” with ideas about terrorism, extremism, radicalisation, etc. frequently taken for granted. IR would appear as little more than a sophisticated propaganda instrument, offering a thousand different ways of camouflaging real power relations.

If 9/11 were a false flag, this would cast the pre-9/11 work of certain IR scholars with known links to the upper echelons of US state power in a new light. For example, if “Islamic terrorism” is a manufactured pretext for US military interference in Muslim-majority countries, then what are we to make of Huntington’s (1997: 58) prophetic drawing of the battle lines between “the West” and “Islam,” including reference to “half a dozen young men […], between their bows to Mecca, putting together a bomb to blow up an American airliner”? Or Richard Betts’ warning that “enemies might attempt to punish the United States by triggering catastrophes in American cities,” specifically citing the threat of a “radical Islamic group” (cited in Lipschutz, 1999: 423)? Huntington and Betts’ ties to the CIA were exposed in the 1980s.

If 9/11 were staged to win popular support for the US invasion of Afghanistan, then what are we to make of Brzezinski’s (1997: 210, 25) argument that the “geostrategic imperatives” of “American primacy” require gaining control of the oil-rich areas of central Asia but that persuading a sceptical US population of the plan will prove “difficult […] except in the circumstance of a truly massive and widely perceived direct external threat,” viz. “the shock effect of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor”?

How should we interpret Carter, Deutch, and Zelikow’s (1998: 81) prediction of a “transforming event” that would, “like Pearl Harbour […] divide our past and future into a before and after,” involving “loss of life and property unprecedented in peacetime,” and necessitating “draconian measures, scaling back civil liberties, allowing wider surveillance of citizens, detention of suspects, and use of deadly force”? Deutch was CIA Director in 1995/6 and in 1997 he co-chaired the Catastrophic Terrorism Study Group with Carter. Zelikow was lead author on the 2002 USS National Security Strategy and Executive Director of the 9/11 Commission.

Is it mere coincidence that the Project for a New American Century (2000) claimed that the rebuilding of America’s defences (specifically involving a new US Space Command) would be a drawn-out affair “absent some catastrophic and catalyzing event – like a new Pearl Harbour”? Or that a commission on the establishment of a US Space Command chaired by Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld (a signatory on PNAC’s founding document) asked in January 2001 whether the necessary funding would occur only after a “Space Pearl Harbour” (cited in Griffin, 2007: 15)?

The disturbing possibility raised by these premonitions of a new Pearl Harbour linked to Islamic terrorism and associated with the very measures that would later be implemented as part of the “War on Terror,” is that the IR discipline may have helped to frame the “War on Terror” narrative in advance.

Van der Pijl (2014: 234) is pessimistic about the prospects for the IR discipline to renew itself: “A discipline led by scholars of this moral calibre cannot be expected to restore its intellectual integrity. Under conditions of the growing precariousness of academics at all levels, few of the rank and file can afford to take their distance from such leading scholars either.” Yet, it is important not to lose sight of what is achievable. As MacQueen observes (see Zuberi, 2013), “When you think about the potential power of universities – not a formal, political power, but an informal power that comes through credibility, high status in society, and influence – they could be stopping this whole thing in its tracks. But they’re not.”

Imagine if academics did start to cast off their cognitive and ethical shackles and come out against the official 9/11 narrative. That would lend considerable weight to the public crescendo of calls for a new 9/11 investigation. Consider the potential consequences: If the official account were falsified and the event adjudged a false-flag attack by a transnational criminal cabal, several things would happen. The War on Terror would come to an immediate halt. Indictments would be issued and criminal trials held until justice was served. Forgiveness of the Muslim world would be sought […] And not an ounce of additional police-state control of innocent citizens anywhere in the world would be needed in order to achieve these worthwhile goals. (Benjamin, 2017: 392)

Perhaps this is a rose-tinted view of how things could be. Perhaps the reality would be something closer to civil war in the United States. At any rate, if academics are serious about pursuing and defending the truth, the first place they need to start is 9/11 truth.

Note

* Griffin (2004, 2-4) cites a range of international opinion polls showing that even in the years immediately after 9/11, significant proportions of the populations of the United States, Canada, and Germany had doubts about the official narrative. According to a CBS/New York Times poll taken in April 2004, for instance, “an astonishing 72 percent of the American people believed the Bush administration to be guilty of a cover-up, at least to some degree, of relevant information it had prior to the attacks of 9/11” (Griffin, 2005: 3).

yogaesoteric

May 19, 2020