The ‘Disappearance’ of Polio (I)

A story about how to vaccinate people against a friendly pathogen which helps humans to aquire natural immunity, and about vaccine production and vaccine approval despite harmful effects

Dr. Suzanne Humphries is a conventionally educated medical doctor who has taken the walk into, around, and out of the allopathic paradigm. She fully and successfully participated in the conventional system for 19 years, witnessing first-hand how that approach fails patients and creates new disease time and again. Prior to medical school, she earned a bachelor’s degree in physics from Rutgers University. The following article is a series of extracts from Dr. Suzanne Humphries’ book Dissolving Illusions.

“I also looked at their children and wondered why they got so sick. This time the answer came rather quickly and from the mouth of an Aboriginal woman: ‘Before the white man came, we had good health and no sickness.’” – Dr. Archie Kalokorinos.

“Morris Beale, who for years edited his informative publication, Capsule News Digest, from Capitol Hill, offered a standing reward during the years from 1954 to 1960 of $30,000, which he would pay to anyone who could prove that the polio vaccine was not a killer and a fraud. There were no takers.” – Eustace Mullins (1923-2010), Murder by Injection.

“Live virus vaccines against paralytic poliomyelitis, for example, may in each instance produce the disease it is intended to prevent; the live virus vaccines against measles and mumps may produce such side effects as encephalitis. Both of these problems are due to the inherent difficulty of controlling live viruses in vivo [once they are placed in a live person]”. – Jonas and Darrell Salk, Science, March 4, 1977.

The polio story is a haunting one: long, complicated, and ugly. It’s not a story you will have read or that the medical profession will be able to tell. Beyond the smoke and mirrors lie sketchy statistics, renaming of diseases, and vaccine-induced paralytic polio caused by both the Salk, and the Sabin vaccines. Dr. Albert Sabin’s oral polio vaccine (OPV) continues to cause paralysis in vaccine recipients today.

Despite many well-documented historical problems, polio and smallpox vaccines serve as the anchor for vaccination faith today. The subject stirs passion in those who believe their ancestors were affected by the dreaded virus or their children could be crippled by it today.

Many believe that a disease called polio has been eradicated in the Western hemisphere. Most everyone thinks that polio was eliminated by vaccination. But to fully understand where polio went, one must understand what polio was. Then, it becomes clear that it is impossible to eradicate it with a vaccine. However, the vaccine did lend itself to many well-documented, although not well-known, problems.

What poliomyelitis (‘polio’) is

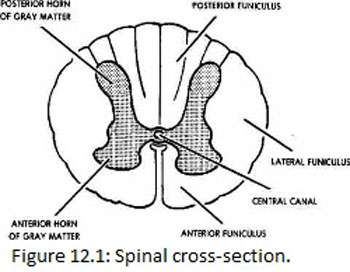

The term poliomyelitis is a description of spinal pathology. The meaning of the word comes from Greek Polios (gray), muelos (marrow), itis (inflammation) and denotes inflammation of the gray matter of the spinal cord. The gray matter is labeled here on the cross section of the spinal cord. Poliomyelitis can occur in the brainstem and the spinal cord.

The result of this inflammation, whether chemical or viral, is reflected by certain characteristic muscular symptoms that have been conditioned into the consciousness of several generations. The most visible aspects of polio were the braced limbs, iron lungs, deformities of hips and legs, clubbed feet, and scoliosis. The most terrifying cases represent the most serious form of polio called bulbar poliomyelitis, where the brain stem is involved and the death rate is highest. Poliomyelitis was widely believed to be caused by a virus that infects the intestinal tract and moves into the body.

Prevalence of polio, 1912-1969

Since the early 1900s, we have been indoctrinated to believe that polio was a highly prevalent and contagious disease.

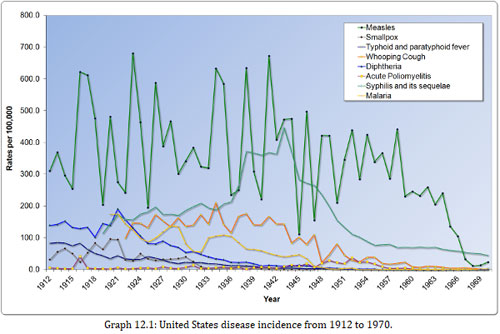

Graph 12.1 depicts the incidence of various diseases in the United States between 1912 and 1970. Poliomyelitis is the line (with square points) at the bottom and reveals that the incidence was very low when compared to that of other infectious diseases.

Given what a low-incidence disease it was, how did polio come to be perceived as such an infamous monster? This is a question worthy of consideration, especially in light of the fact that the rate was far less than other common diseases, some of which declined in incidence to nearly zero with no vaccine at all.

Natural (wild) poliovirus

It is easy to assume that poliovirus appeared abruptly or somehow changed in the 1900s to become as problematic as it was alleged to be. Naturally existing poliovirus was a common bowel inhabitant for millennia, always there, continuously circulating through humans, but never causing paralysis until later when something changed.

The key question is: What opportunities could have arisen that afforded poliovirus the ability to cause epidemics in the early 20th century?

Under healthy environmental and dietary conditions, certain populations had antibodies to all three types of the virus and did not develop paralysis or have significant symptoms after infection.

Native tribes were immune to polio

The remote Brazilian Xavante tribe serves as an example. This tribe was relatively untouched by modern man because they fought encroachments by slaughtering anyone who got close. There was a brief period of time in the 1700s when some of the natives lived among the white men until they realized that doing so brought waves of disease and death upon them. Those who survived fled and moved farther west in an attempt to isolate themselves. Around the 1950s, a few Indian health service members managed to get some cooperation for a study that evaluated the resistance to disease and the immune status of those native people. The results of the pilot study were published in 1964.

Isolated native tribes seem to have had no problem with the infections that were plaguing white men, even though blood results showed that the natives were indeed exposed and infected by many of those very same germs. Dr. Neel found that: “The paradox of a virtual absence of paralytic poliomyelitis among such heavily infected groups as this [referring to the Xavante Indians], despite high antibody titers, is well known, but the interpretation of the observation remains under discussion.”

These isolated people, who had not adopted any of the habits or medical interventions that are now known to increase susceptibility to poliomyelitis, were fully infected and immune! Native Indian populations had evidence of infection with all three strains of poliovirus, but developed no poliomyelitis whatsoever. “…studies of antibody avidity according to the techniques of Sabin (1957) were made on randomly selected specimens. All specimens were positive for antibodies to all three types of poliomyelitis, providing additional confirmation of the validity of the findings [that the Indians were all immune and none of them paralyzed]… The percentage of positive reactors is striking.”

These people had true herd immunity: “all of the 60 persons tested with both techniques have antibodies to type I, 59 [had antibody] (98.3 ± 1.7 per cent) to type II, and 56 [had antibody] (93.3 ± 3.2 per cent) to type III.”

Within Neel’s paper, there is ample documentation and reference to the fact that native populations, when left to their natural diet and habitat, can become infected with influenza, salmonella, and measles. But the diseases do not spread clinically within the tribe, and mortality is nonexistent. “In this instance, under-reporting hardly can be invoked as an explanation, one must conclude that in the Peruvian altiplano most infections are subclinical or give rise to only trivial illness. The demographic data make it clear that the eight persons positive for influenza did experience their disease while in contact with other members of the tribe. Why did the disease not spread?”

Dr. Albert Sabin, inventor of the oral polio vaccine, also noted in 1947 that native peoples were infected by poliovirus before the age of five, and yet there was no paralysis among them. There was, however, a significant rate of paralytic poliomyelitis in American servicemen in the same areas. Paralytic disease was common in the colonizing communities but not in natives. “… The most important question: why did paralytic poliomyelitis become an epidemic disease only a little more than fifty years ago, and as such why does it seem to be affecting more and more the countries in which sanitation and hygiene, along with the general standard of living, are presumably making the greatest advances, while other large parts of the world, regardless of latitude, are still relatively unaffected?”

Sabin said that the virus was present all over the world and that asymptomatic infection was widespread, even in regions where epidemics were unknown. The incorrect assumption by Dr. Sabin was that polio had anything to do with wealth per se. It probably had more to do with the subtle deterioration of innate immunity due to what wealthy people and American servicemen were spraying in the environment, what doctors were doing to them, and other lifestyle habits.

Dr. Archie Kalokerinos, a medical doctor who spent his career tending to the aboriginal people of Australia, was told repeatedly by the elders that the tribes had no disease until the white men arrived and that they didn’t even have names for these diseases.

Diet and environment give susceptibility to paralitic polio

Although Dr. Sabin was simply puzzled about the clean and advanced parts of the world getting sick, he failed to connect the rate of paralysis to easily identifiable factors. Examining what changed in the environment and the human diet and how that clearly affected the susceptibility to paralysis in developed areas is key to understanding polio.

The white man’s diet of refined and processed foods with the resultant lack of vitamins, the environmental and agricultural poisons, and specific invasive medical procedures all contributed to the rise in susceptibility of people living in industrialized parts of the world.

But by the time those connections were made, disease-causing food was well ingrained in the modern palate. Medical advances were met with gratitude even though many of them were dangerous and overused. Refined sugar, white flour, alcohol, tobacco, tonsillectomies, vaccines, antibiotics, DDT, and arsenic had become financial golden calves that led humanity blindly down a spiral of disease and misery.

Unfortunately, the paralysis was uniformly attributed to poliovirus infections which thus justified and prioritized vaccine research at all costs. Many thousands of people were needlessly paralyzed because the medical system refused to look at the consequences of these golden calves, gave only lip service to the success of the Sister Kenny treatment of paralysis (discussed later in this chapter), and concentrated solely on vaccine research.

What polio was and where it is now

Before the vaccine was in widespread use, many distinct diseases were naively grouped under the umbrella of ‘polio.’ The following list represents a few that could have been categorized and documented as polio prior to 1958:

– Enteroviruses such as Coxsackie and ECHO

– Undiagnosed congenital syphilis

– Arsenic and DDT toxicity

– Transverse myelitis

– Guillain-Barré syndrome

– Provocation of limb paralysis by intramuscular injections of many types, including a variety of vaccines

– Hand, foot, and mouth disease

– Lead poisoning

These are all conditions that still exist today and that a polio vaccine could not prevent.

The face of polio may have changed, but it was mostly due to the power of the pen, advances in diagnostic and life-support technology, removal of certain toxic influences, and advancements in physical therapy.

Specific polio diagnosis was not pursued with laboratory testing before 1958. The diagnostic criteria for polio were very loose prior to the field trials for the vaccine in 1954.

Before the vaccine was deployed, health-care professionals were vigilantly programmed to be on the lookout for polio. After the trials, they were vigilantly noting who developed polio – vaccinated or unvaccinated – and made every effort to diagnose a non-polio illness in a vaccinated person.

Dr. Bernard Greenberg, head of the department of biostatistics of the University of North Carolina School of Public Health and chairman of the Committee on Evaluation and Standards of the American Public Health Association, stated in 1960: “Prior to 1954 any physician who reported paralytic poliomyelitis was doing his patient a service by way of subsidizing the cost of hospitalization and was being community-minded in reporting a communicable disease. The criterion of diagnosis at that time in most health departments followed the World Health Organization definition: ‘Spinal paralytic poliomyelitis: signs and symptoms of nonparalytic poliomyelitis with the addition of partial or complete paralysis of one or more muscle groups, detected on two examinations at least 24 hours apart.’ Note that ‘two examinations at least 24 hours apart’ was all that was required. … Laboratory confirmation and presence of residual [longer than 24 hours] was not required.”

The practice among doctors before 1954 was to diagnose all patients who experienced even short-term paralysis (24 hours) with ‘polio.’ In 1955, the year the Salk vaccine was released, the diagnostic criteria became much more stringent.

If there was no residual paralysis 60 days after onset, the disease was not considered to be paralytic polio. This change made a huge difference in the documented prevalence of paralytic polio because most people who experience paralysis recover prior to 60 days.

Dr. Greenberg said: “The change in 1955 meant that we were reporting a new disease, namely, paralytic poliomyelitis with a longer-lasting paralysis. Furthermore diagnostic procedures have continued to be refined. Coxsackie virus and aseptic meningitis have been distinguished from paralytic poliomyelitis. Prior to 1954 large numbers of these cases were mislabeled as paralytic poliomyelitis. Thus, simply by changes in diagnostic criteria, the number of paralytic cases was predetermined to decrease in 1955-1957, whether or not any vaccine was used.”

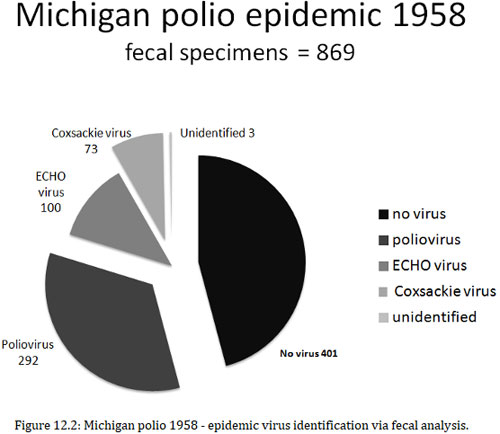

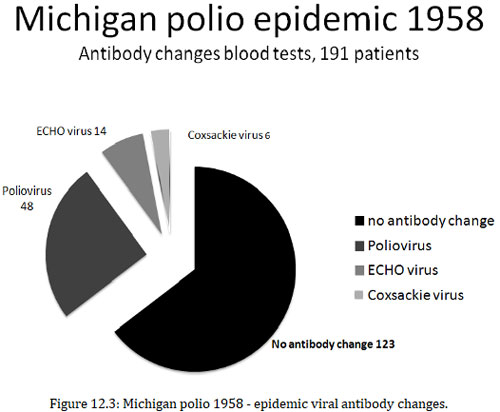

As a case in point on how much paralytic disease thought to be polio was not at all associated with polioviruses, consider the well-documented Michigan epidemic of 1958. This epidemic occurred four years into the Salk vaccine campaign. An in-depth analysis of the diagnosed cases revealed that more than half of them were not poliovirus associated at all (Figure 12.2 and Figure 12.3).

There were several other causes of ‘polio’ besides poliovirus. “During an epidemic of poliomyelitis in Michigan in 1958, virological and serologic studies were carried out with specimens from 1,060 patients. Fecal specimens from 869 patients yielded no virus in 401 cases, poliovirus in 292, ECHO (enteric cytopathogenic human orphan) virus in 100, Coxsackie virus in 73, and unidentified virus in 3 cases. Serums from 191 patients from whom no fecal specimens were obtainable showed no antibody changes in 123 cases but did show changes diagnostic for poliovirus in 48, ECHO viruses in 14, and Coxsackie virus in 6. In a large number of paralytic as well as nonparalytic patients, poliovirus was not the cause.”

Transverse myelitis, viral or aseptic meningitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), chronic fatigue syndrome, spinal meningitis, post-polio syndrome, acute flaccid paralysis (AFP), enteroviral encephalopathy, traumatic neuritis, Reye’s syndrome, etc., all could have been diagnosed as polio prior to 1958.

(to be continued)

yogaesoteric

February 25, 2021