The great biometric data theft

Roblox is one of the most popular game platforms, with millions of users accessing it every day. Like more and more apps and online networks, the company’s latest security measure now requires every user, everywhere, to pass a facial age estimation test before the chat can be used.

The policy, enforced through a third-party company called Persona, is being sold as a step towards what Roblox calls the “gold standard for communication security”.

So this is the new standard, apparently: biometric obedience in exchange for communication.

In the new system, Roblox sorts its millions of players into six age groups, starting with “under nine” and ending with “over twenty-one”.

Each grade level brings with it communication restrictions. For example, a 14-year-old can send messages to other 14-year-olds, 13-year-olds, or younger, but not to a 16-year-old.

The company argues that this segmentation prevents adults from chatting directly with minors, while maintaining “age-appropriate” social circles.

It’s an idea that sounds reasonable in theory but is bureaucratic in practice – a digital playground monitored by date of birth. But the implications of the growing drive for identity verification are profound.

To give the whole situation an official air, Roblox pointed to the precision of the Persona technology:

“The technology used by our provider Persona has been tested and certified by independent laboratories. The age estimation models used achieved a mean absolute error of 1.4 years for users under 18, based on tests by the Age Check Certification Scheme in the United Kingdom.”

In other words, the algorithm can be off by a year and a half, but that is apparently enough to decide who is allowed to talk to whom.

Anyone who disagrees with their assigned age can appeal by presenting identification. The company describes this as an “alternative method” of verification, not as a second level of surveillance.

Alongside this introduction comes another new feature: a program called Roblox Sentinel, described as a machine learning system that monitors “multiple signals” to detect behaviour that doesn’t match a user’s claimed age. If the AI suspects that someone is lying about their age, they will be prompted to re-scan their face.

Roblox claims its goal is to prevent child exploitation before it occurs. However, it’s noteworthy that the system doesn’t just verify age. It constantly monitors, analyses behaviour, and creates a profile for each user.

The Great Biometric Drift

Roblox is not alone in this. YouTube and other major platforms have also introduced facial age verification, often with the same “security” logic.

The problem is that these systems rely on biometric data – facial geometry – which cannot be altered, deleted, or truly anonymized.

Companies promise to handle data responsibly, but promises do not change the fact that users are trained to give away their likeness just to be allowed to communicate.

Even children are learning that a digital face scan is the entry fee.

What is emerging here is a cultural shift towards digital ID systems managed by private companies.

A generation ago, the idea of submitting a live facial scan to chat with friends would have sounded dystopian. Today, it’s considered an “improvement in user safety.”

In the case of Roblox, refusing the scan means the complete loss of chat access – the platform’s central function.

The directive redefines privacy as a trade-off: those who want to connect should first give up a piece of their identity.

The more widespread these systems become, the more they shape expectations. Children who grow up with Roblox learn that being online means verifying themselves against a machine.

They internalize the idea that trust is granted by algorithms and not through behaviour.

Over time, these biometric gates will be extended to other areas of Roblox and beyond. Once normalized, they are rarely reversed.

The habit of proving one’s age with one’s face will accompany one to other corners of the web and quietly redefine what “security” means in the digital age.

For Roblox, this may be a business decision. For everyone else, it’s another lesson in how convenience and control have merged into a single product. The company calls it security. The rest of us might call it education.

The rollout of Roblox is just one part of a much larger pattern. Across industries – from banking to education to entertainment – biometric and digital identity systems are being woven into everyday processes.

Each new “verification upgrade” may seem harmless on its own, but together they form a network from which opting out becomes virtually impossible.

Online security is important, but linking security to permanent identification introduces a different kind of danger.

The normalization of digital ID systems is turning the internet from a place of self-presentation into a place of authorization verification. Once this shift takes hold, privacy ceases to be a right and becomes something people need to actively defend.

Persona’s past problems

Persona, the company Roblox relies on to decide who can chat, brings its own legal baggage. In Washington v. Persona Identities, Inc., plaintiffs Charles Washington and Katie Sims filed a class-action lawsuit in Illinois, accusing the company of violating the state’s Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA).

The lawsuit stated that Persona “unlawfully possessed and profited from the biometric information of the plaintiffs by failing to publicly disclose its policies regarding the retention and destruction of biometric data when that information was collected.”

The case stemmed from Persona’s work for DoorDash, where drivers had to submit “live selfies” and photos of their driver’s licenses for verification. Persona’s software analysed these images and saved scans of each driver’s facial geometry.

Persona attempted to transfer the case to private arbitration, arguing that it was protected by DoorDash contracts with the drivers. The Illinois Court of Appeals disagreed, ruling that Persona “has no legitimate basis to force the plaintiffs’ claims into arbitration” because it was not a direct party to those agreements.

The court described Persona’s role as merely assisting with verification, not conducting background checks independently, and referred the case back for further proceedings.

The lawsuit highlighted how fragile the concept of “trust” is in the biometric economy. Persona presents itself as a secure verification service, but its practices have already been challenged under one of the strictest data protection laws in the US.

For Roblox players who now have to pass Persona’s facial scans, this legal backstory raises an obvious question: What exactly occurs to these scans when the game is over?

Coinbase and the entrance fee

Coinbase, one of the largest cryptocurrency exchanges, is now facing similar allegations.

A lawsuit filed in federal court in Illinois alleges that the company violated BIPA by collecting facial biometric data without the legally required consent and by failing to publish a policy explaining how that data is stored or deleted.

According to the lawsuit, Coinbase used the verification providers Jumio and Onfido to process users’ facial images during account opening.

Although Onfido was not named as a defendant, the plaintiffs argue that Coinbase itself is responsible for obtaining written consent before collecting biometric information.

The dispute follows an earlier phase of arbitration chaos. In March 2024, almost 8,000 people filed arbitration requests, with thousands more following shortly thereafter.

Coinbase attempted to have the claims referred to a minors court and subsequently refused to pay the arbitration fees after this request failed. The plaintiffs paid their share, but Coinbase did not. This decision effectively terminated the arbitration proceedings and paved the way for new litigation.

This is not Coinbase’s first BIPA dispute. A previous lawsuit from 2023 was referred to arbitration and later dismissed without prejudice, meaning it could return if the arbitration fails.

Coinbase is not alone. Walmart, the USA’s largest private employer, recently settled a BIPA case involving its Spark delivery app, which used Persona-provided facial biometrics to register and authenticate drivers.

The plaintiffs accused Walmart of failing to obtain proper consent before collecting the data. The company agreed to a settlement, the financial details of which remain confidential.

Walmart also faced further lawsuits from BIPA regarding its biometric time-tracking systems for employees. Each of these cases demonstrates how easily companies have integrated biometric data collection into everyday operations – often without explaining the consequences.

Across all industries, biometric compliance is creeping into the background of everyday life.

The trend points in one direction: a future in which identity verification becomes a prerequisite for online existence.

The more familiar something feels, the less likely anyone is to question it. The machines may confirm who we are, but the price is that they will also know exactly how to find us.

ID.me has signed a $1 billion framework agreement with the US Treasury Department – a five-year deal that allows the company to provide authentication and identity verification across several departmental programs. This cements a private company’s control over vast amounts of the public’s personal data.

Federal officials describe the agreement as progress in online security and fraud prevention. However, the growing reliance on the biometric infrastructure of a single provider goes far beyond efficiency.

It shifts the responsibility for verifying the identity of millions of citizens from public institutions to a profit-oriented intermediary, where the handling of this data is guided more by commercial incentives than by constitutional principles.

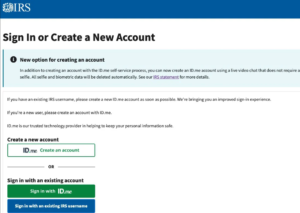

ID.me is no newcomer to federal contracts. Its relationship with the Internal Revenue Service dates back years, with contracts worth tens of millions of dollars.

The IRS recently signed an $86 million contract for the exclusive use of the company’s authentication services. Users will be required to verify their identity by submitting documents and undergoing facial recognition.

Public outcry in 2022 forced the IRS to abandon its requirement for facial recognition and offer a video chat with a live agent as an alternative. Nevertheless, ID.me remains a key component of how Americans verify their identity to access tax information and file tax returns online.

Other agencies followed suit. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services now uses ID.me for Medicare.gov.

The Department of Veterans Affairs and the Social Security Administration rely on it for access to benefits. In 2025, the General Services Administration expanded ID.me’s reach through a contract allowing it to serve multiple agencies under the Federal Supply Schedule.

By this time, ID.me had become infrastructure.

When public identity becomes private property

Every new contract blurs the line between public service and private administration. Outsourcing identity verification concentrates enormous amounts of personal information under the control of a single company: names, ID numbers, facial images, and even behavioural data related to registrations.

Once this model is established, citizens will no longer authenticate themselves with the state itself.

You authenticate yourself with a company that decides how long data is stored, what security measures apply, and how transparently information is provided.

The process may appear seamless to the user, but it signifies the privatization of a cornerstone of civic life: the ability to prove one’s identity without selling it.

What began as an attempt to simplify logins and prevent fraud has evolved into a commercial identity network interwoven with federal bureaucracy. Access to essential services such as healthcare, pensions, and tax processing now depends on compliance with the biometric standards of a private company.

Congress criticism and pandemic aftermath

The company’s growing role comes despite critical findings from two US congressional committees that examined its performance during the pandemic.

Members of Parliament found that ID.me had misled authorities and the public about both waiting times for virtual interviews and the actual extent of prevented unemployment fraud.

According to the report, ID.me informed federal authorities that manual verification of failed facial scans takes approximately two hours.

In reality, average wait times exceeded four hours, with some states reporting delays of nine hours or more. The company also removed appointment options for virtual consultations, leaving people with shared or public computers inaccessible for unemployment benefits.

Representative James Clyburn, then chairman of the special subcommittee on the coronavirus crisis, condemned the company’s handling of taxpayer-funded programs:

“It is deeply disappointing that a company that received tens of millions of dollars in taxpayer money to help Americans obtain these benefits may have hindered their access to this crucial assistance. ID.me’s practices risked making urgently needed support unavailable to Americans who do not have easy access to computers, smartphones, or the internet.”

Representative Carolyn B. Maloney, Chair of the Oversight and Reform Committee, criticized the company’s transparency:

“In some cases, ID.me removed important customer service offerings, making it difficult for users to speak with trusted contacts. I am also deeply concerned that ID.me provided inaccurate information to federal agencies in order to secure millions of dollars in contracts.”

The picture painted by the investigation was one of dysfunction. During the pandemic, ID.me became a digital bottleneck for unemployment claims, with millions of applicants stuck in virtual queues, while the company publicly presented itself as a fraud prevention success story.

The resistance

Privacy activists have taken notice. The Electronic Privacy Information Center, together with several civil rights organizations, has called on federal and state authorities to terminate their contracts with ID.me and similar providers.

They argue that biometric verification undermines equal access to government services, especially for people without the necessary technology or resources.

Following the criticism, the IRS abandoned its plans to make facial recognition mandatory for taxpayers accessing online services.

Nevertheless, the company continues to win new federal contracts, while scrutiny of its methods and data policies increases.

The new bureaucracy of the face

The conflict surrounding ID.me exposes the contradictions at the core of the digital identity movement.

Companies claim to be modernizing access and fighting fraud, but their systems rely on invasive data collection and opaque decision-making.

Citizens are expected to trade privacy for convenience, often without realizing that they are entering a commercial system that treats identity as a monetizable commodity.

Organizations like EPIC are calling for direct resistance, for example through initiatives like the “Dump ID.me” petition, and warn that the normalization of mandatory biometric verification will outlast every single contract term. The underlying message is simple: efficiency in government should not require the surrender of biometric data.

The deeper question is what kind of society emerges when proof of one’s identity is inextricably linked to corporate databases.

Once the right to exist in a digital space depends on a facial scan, privacy ceases to be a protective mechanism. It becomes a permission that can be revoked.

yogaesoteric

February 6, 2026

Also available in:

Français

Français