The History of a Fundamental Childhood Vaccine: Influenza

“Sometimes you get the feeling that there is a whole industry almost waiting for a pandemic to occur.” – Dr. Tom Jefferson, Cochrane Review epidemiologist and influenza expert, in a 2009 interview about swine flu.

“We are supposed to be prepared for a pandemic of some kind of influenza because the flu watchers, the people who make a living out of studying the virus and who need to attract continued grant funding to keep studying it, should persuade the funding agencies of the urgency of fighting a coming plague.” – Philip Alcabes, in Dread: How Fear and Fantasy Have Fueled Epidemics from the Black Death to the Avian Flu (2009).

Before the flu was a “vaccine-preventable illness”

Dr. Thomas Francis, Jr., who could be called the father of the U.S. influenza vaccine program, was a man who believed in God and thought that his endeavors were for the good of people. With a Salvation Army nurse for a mother and a father who was a steelworker and Presbyterian minister, his family life was steeped in medicine, religion, and public service. He became a pioneer and pillar of flu vaccine research – and arguably public health policy in the process. He is credited with first isolating influenza A virus and creating the first vaccines against influenza A and B while working for the U.S. military in the 1940s. After studying influenza at the Rockefeller Institute in the 1930s, he so impressed the Rockefeller family that he became their personal physician. A bulldog for factual evidence, he set the standards and practices for medical research in vaccines that we have today, through the way he saw the world and the policymakers and scientists he mentored. Jonas Salk, most known for creating the first polio vaccine, started under Francis’ wing. Arnold Monto, current chair of the FDA’s advisory committee on vaccines and co-director of one of the five centers in the U.S. that collects flu data for the CDC, was recruited to join him in research at the University of Michigan.

It has been said that Francis could tell how old a person was by looking at the flu antibodies they carried and comparing them to when that strain was prevalent. How did he do this? Francis saw that the immune system kept a memory of the first time it encountered the flu virus. Interestingly, he was so frustrated by the fact that influenza changes frequently that he called it a “sin.” The body’s memory of its first flu, a natural process of the immune system, was an “original sin” in his eyes that was punished by getting the flu over and over.

But what is the flu? According to Francis, the flu is a lot of aspects.

The Spanish flu and the military’s war on diseases

“Influenza has always been a mixture of romance and terror; of fact and fable; of new and old ideas. Its various popular names: the jolly rant, the new delight, the nee acquaintance, gallants’ disease, the fashionable illness, influenza di coeli, la grippe, flu, this virus – all indicate a light-hearted annoyance. But interspersed are the tales of damaging experiences.” – Dr. Thomas Francis, Jr., in a reading to the American Philosophical Society, April 1960.

Before people were told about germs and bacteria and viruses around the turn of the 19th century, the term “influenza” was broadly used to describe a symphony of symptoms: fever, chills, cough, aches, nausea, fatigue, runny or stuffy nose. Influenza is an Italian word that references the influence of the stars, or God, or fate, on the human condition. It’s an unseen influence that many studied through astrology before it was studied through microscope. The use of the term influenza was a general way to describe a whole slew of illnesses, with outcomes ranging from mild annoyance to fatal.

Human beings get sick – sometimes hundreds or thousands or millions at a time – and the story many of us believe is that we didn’t know why, until we learned about germs. Today, there are scientists who will tell you about influenza viruses and show you where certain strains originated, tracing lineages like a family tree or the lines of a pedigreed dog. But hundreds of years of medical research have left us exactly where we started with the flu, despite medical categorization of influenzas A, B, C, D, and annual predictions of which member of the flu family will be home for the holidays. The sweeping term “influenza” was narrowed to the name of a virus, but that understanding hasn’t stopped people from getting the flu year after year. And it hasn’t stopped fears of a flu pandemic which can flare at any time.

Americans were generally viewed as the last holdouts in accepting germ theory. In the 1930s, between two world wars, the idea that sickness was created by outside invaders such as bacteria and viruses finally took hold of the American medical community.

Prior to the mass adoption of germ theory as the dominating way to approach sickness, “The family, as the center of social and economic life in early American society, was the natural locus of most care of the sick.” Americans used medicinal plants or homeopathy, looked to spiritual healers and wise elders (often women), and passed their healing techniques via stories and pooling of community knowledge.

The early 1900s was riddled with fear. Wars were raging, and from 1918 to 1919 people experienced one of the worst pandemics known to human history, which they called the Spanish flu. The pandemic was brutal. Illness struck suddenly and progressed quickly and was unlike any other influenza known to man at that time. It killed more people than the Black Death had taken a century before. People’s symptoms went beyond typical fevers and aches – many patients who came down with the illness also coughed up blood, had nosebleeds, brain hemorrhages, and other blood abnormalities. Doctors who tested the blood of those who were ill found its ability to coagulate to be weakened. It is estimated that half a billion people were infected, and 20 to 50 million people died worldwide.

The natural human inclination to find safety again made the landscape fertile for germ theory to root. As you will read, scientific thought converged with military needs, causing people to readily embrace the idea that there was an external “bad guy” that could be identified and therefore fought. The Third Reich of Nazi Germany politicized and promoted the ideas of germ theory and infections, as the hierarchy of organisms and combative nature of survival of the fittest served their eugenic goals. The Darwinian concept of survival of the fittest helped solidify the germ theory: humans vs. microbes. “The conception of the microbial world as part of a larger natural order, ruled by immutable laws of development, was a large part of the theory’s scientific appeal.” If we can categorize it, we can control it.

Dr. Stefan Lanka, who has dared to question germ theory, has pointed out, “It is important to note that the theories of fight and infection were accepted and highly praised by a majority of the specialists only if and when the countries or regions where they lived were also suffering from war and adversity. In times of peace, other concepts dominated science.”

Medical historians will tell you of two competing schools of thought on “germs.” In germ theory, people and animals are healthy when they are free of germs; it is the invasion of an outside pathogen that causes us to be sick. This way of thinking requires one to constantly be on the defense against these “bugs,” and to become reliant on help from medical practices or drugs to stop symptoms by killing the pathogen. Louis Pasteur (of pasteurization fame) is generally thought to be the father of this approach.

In its inherently adversarial style, germ theory had to triumph over another popular way of viewing illness in order to survive. That theory is generally called terrain theory, which states that humans and animals coexist with germs and it is their environment that is the determining factor in illness. Terrain theory says that your diet, exercise, air quality, and general constitution either keep you healthy or make you susceptible. You could say, when it comes to germs, correlation doesn’t equal causation. The presence of bacteria, or what scientists call viruses, when a person is ill doesn’t necessarily mean the germ caused the symptoms.

Interestingly, even though questioning germ theory puts you in the tinfoil hat club, terrain theory is gaining interest again. Covid exposed so many cracks in our public health approaches that people started asking forbidden questions. You can also see resonance of terrain theory in the emergence of “N=1” medicine or experimentation in the biohacking community, where people experiment with different ways to reach their own optimal health by altering the toxins in their environment, the quality of food and water they take in, their state of consciousness and emotional wellbeing, and other unique factors that weave together to manifest our states of health or disease.

Once germ theory became an inseparable part of allopathic medicine in the 1930s, the term influenza went from being a collection of symptoms to a specific disease. With one identified disease to fight, it became rational to look for the magic bullet to fight it. Enter the vaccine, which was, conveniently, an emerging field.

Using germ theory, which has become the foundation for standard allopathic medical practice, the flu is viewed as unique among diseases. It mutates quickly and frequently, so it’s possible to catch influenza over and over again. Having the flu is so common the disease has been likened to a season because of the time of year the illness typically surges. It’s even possible to get infected with more than one strain at once, where a person could then be host to a new influenza strain resulting from a genetic swap from the other two, according to the CDC.

How do you know when you have the flu? Usually, you don’t. When was the last time you got your flu test to confirm the presence of the influenza virus when you felt sick? Generally, we still know we have a bucket of symptoms and what we call the flu is no different than it has been for centuries. The generalized influenza of the past is now labeled influenza-like-illnesses (ILI) by medical science, distinct from identification of a virus. Many other diseases have similar symptoms – pneumonia and covid, for example. In general, epidemiologists can’t tell you if reported cases are one or the other or neither.

But what they could tell you in 1940, with the prospect of the United States being pulled into World War II, was that it was a matter of national security for the U.S. to figure out how to save their soldiers from another 1918-style disaster.

The influenza vaccine was a magic bullet for the military

The Spanish flu, as it was called, did not just kill infants, the elderly, and the infirm. Terrifyingly, it affected people at the height of their health and strength: people in their late teens and 20s, especially men. In other words, those who could fight in the army. The sudden explosion of disease, primarily among those who were or would be eligible to serve in the military, had some U.S. military officials questioning whether the outbreak was a deliberate act of biowarfare.

Stopping sickness became a military priority. No one knows the exact numbers, but “according to one estimate, influenza accounted for nearly 80 percent of the war casualties suffered by the U.S. Army during World War I.” Others estimate about half of the 112,000 soldiers killed were killed by disease (mostly flu), not battle wounds. The development of a vaccine against influenza became a patriotic duty and necessity for national security.

In 1941, a Board for the Investigation and Control of Influenza and Other Epidemic Diseases was created, eventually becoming known as the Armed Forces Epidemiological Board. Already famous for his studies of influenza, Dr. Thomas Francis was tapped by the U.S. government to head a new Commission on Influenza of the Armed Forces Epidemiological Board. Francis recruited a young Jonas Salk, whom he had mentored through his education at NYU and the University of Michigan, to head the influenza research for the army. Francis and Salk believed that a “killed” flu virus would work to trigger the body’s immune system enough to create an immune response. (Salk would go on to create the polio vaccine favored by the United States in the 1950s post-war polio campaigns, where he would interact with Francis again.)

Hygiene and sanitation practices had worked to reduce the incidence of disease in cities and the greater population, but the military does not always have such luxuries when crammed into transport vehicles and barracks. Servicemen and women also face a monumental increase in stress, which can weaken the immune system. The military called for a blunt force tool to fight disease; they turned to vaccines.

The military were the “lead users of vaccine technologies.” In the 1940s alone, “wartime programs contributed to the development of new or significantly improved vaccines for 10 of the 28 vaccine-preventable diseases identified in the 20th century.”

Have you ever noticed that we discuss illness in the language of war? The U.S. even has a Surgeon General. In American “wars” on diseases, they “fight” germs, “kill” bacteria, suffer “attacks” by “invading” pathogens, and either “conquer” disease, or die as a “victim” of sickness. They defend themselves against germs with “shots.” And vaccines were considered a “magic bullet” in the “war on disease”.

This is because medicine as we know it today has its roots in war. Between World Wars I and II, military goals brought together the money and manpower needed to jumpstart the vaccine industry. “Many of the ideological and practical barriers to closer collaboration between industrial, military, and academic institutions collapsed under the threat of war.” The world in which germ theory took root was one of war and adversaries and that’s reflected in the language we use today.

How does influenza spread?

We are told that in 1918, people did not know what caused the pandemic, nor how to stop it from occurring again. In fact, the true cause of the 1918 pandemic is still not settled science. A paper co-authored by Dr. Anthony Fauci in 2008 became headline news in 2022 for an extrapolation that masks cause illness, but the main conclusion of the publication was “the majority of deaths in the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic likely resulted directly from secondary bacterial pneumonia caused by common upper respiratory tract bacteria.” Another paper published in 2008 also hypothesized fatalities were caused by bacteria that led to lethal pneumonia.

From a different perspective, Arthur Firstenberg, author of The Invisible Rainbow: A History of Electricity and Life points out the sudden huge expansion of the use of radio immediately preceded the Spanish flu (just like mass launches of military satellites came before the 1967 Hong Kong flu outbreak, and 5G towers were being installed just before covid hit). The United States entered World War I in 1917, firing up and operating the world’s largest radio network across the country in short order, operated by the U.S. Navy. The Spanish flu shortly followed in 1918, seeming to spring up around the U.S. Navy ships and spread around the world.

Whether influenza could be transferred between humans has been subject to debate for at least a century. A study published in 1919, Experiments to Determine the Mode of Spread of Influenza, found no transmission despite many attempts at taking bodily fluids or excretions from one person and applying them to another (for those curious, check the reference for a more detailed picture). The method and truthfulness of transmission of influenza from the sick to the well continues to elude the best scientists in the world. In 1983, doctor and researcher Robert Edgar Hope-Simpson published A New Concept of the Epidemic Process of Influenza A virus, in the British journal Epidemiological Infections, proposing a “seasonal stimulus” as a reason for the flu. In 2008, still vexed by the mystery of when and where the flu will appear, researchers revisited Hope-Simpson’s hypothesis, asking, “Why does experimental inoculation of seronegative humans fail to cause illness in all the volunteers,” if it is so contagious?

This is no jolly academic debate – our entire influenza vaccine program is premised on the cause of death of the Spanish flu being settled. But if we are not even certain that was the cause of death in 1918, how does a flu vaccine serve us now?

Is the flu vaccine safe?

When a person is injured or killed by a vaccine, they cannot sue anyone, even if the manufacturer made a mistake. Americans can file a petition with the U.S. Health and Human Services department for compensation. This is known by many as vaccine court, and it is the result of the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act, passed in 1986. Since the creation of the 1986 Act‘s compensation program, over 9,000 Americans have been awarded money for injuries or death. Well over half of all of the total claims made and paid were for one single vaccine: influenza. As of February 13, 2023, over 5,500 Americans have been paid compensation for injury or death associated with influenza vaccines.

The 1986 Act also created the vaccine safety signal monitoring system we know as VAERS, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. There are over 200,000 adverse events reported to VAERS for influenza vaccines over the years. Before covid, the influenza vaccine represented the most reported injuries of all vaccines in use (including combination vaccines). These numbers do not include the swine flu fiasco of 1976, where the U.S. government paid out over $93 million to those who were vaccinated for a pandemic they predicted that never occurred. Thousands sued the government for Guillain Barre Syndrome and deaths. The government told people the flu was the same as that of 1918. They also failed to notify people of potential neurological side effects of the vaccine, as reported by an investigation by 60 Minutes.

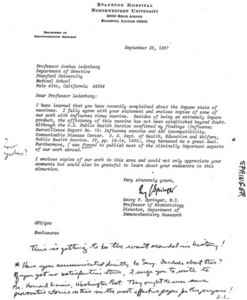

Many have questioned the safety of the flu shots for pregnant women in particular. In the 1970s, Dr. George F. Springer and Mr. Harvey Tritel raised an alarm that the shot being used in the 1960s could potentially create a blood disease in newborns in certain circumstances. Springer wrote to another scientist questioning the purity of the flu vaccine, Dr. Joshua Lederberg, saying even though his findings were confirmed, the U.S. Public Health Service “harassed me a great deal,” and he had trouble publishing his findings. The information was shared in the CDC’s Influenza Surveillance Report No. 73 in December 1962, but the information was not widely reported beyond that. A handwritten note on Springer’s letter that is likely written by Lederberg stated, “This is getting to be the worst scandal in history.” This document and more can be viewed at the collection of Joshua Lederberg Papers at the National Library of Medicine.

The question of safety for pregnant women was revived after the 2009-2010 influenza vaccine. A group called the National Coalition of Organized Women claimed to observe a spike of over 4,000% in fetal death in the VAERS database. The group confronted CDC investigators at a meeting of the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices in October 2010, and it was reported that there were “no unexpected patterns or unusual events.”

Is the influenza vaccine effective?

According to CDC data, the flu shots range from 10% effective to 60% effective since 2004, with an average of 40%. The effectiveness has not been higher than 50% in the last decade. Further, it is widely understood that flu shots will not stop a flu pandemic because the shots are made before a mutation, and it takes months to create a vaccine for another strain.

The bottom line: no one knows how prevalent the flu is – not your doctor, the CDC, or the WHO – and therefore, we can’t truly understand how effective (or ineffective) the shots are. The CDC admits on their website, “Influenza incidence is difficult to quantify precisely, as many or most of those infected may not seek medical attention and are therefore not diagnosed.” Why would a person not seek medical attention? Most likely because they do not need medical intervention because the symptoms are mild. You could say there is an economic factor – they cannot take time off work, don’t have insurance – but in either of those cases, if it got bad enough, they would have no choice but to seek medical care. Further complicating the issue is the fact that influenza-like illnesses, ILIs, get grouped together when cases are reported.

According to Dr. Thomas Jefferson, an expert who has extensively researched and written on influenza vaccines and policy for the Cochrane Review, “The starting point is the potential confusion between influenza and influenza-like illness.” Those presentations of something that looks like influenza, as it is medically defined, never get verified, and simply get clumped together. How many cases of something that looks like the flu are actually the flu? We can’t know.

Jefferson could be considered one of the world’s experts on influenza and its vaccines. He has worked with the Cochrane Review for decades, co-authoring reviews on vaccines for influenza. In a presentation given to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in 2010, he explained, “Vaccines and antivirals have a weak or non-existent scientific base.”

He went on to state, “The consequences are seen in the impractical advice given by public bodies.” Instead of focusing on getting more data, perhaps the CDC should focus on ensuring data collected is accurate.

Today the CDC recommends annual influenza vaccines starting in utero

Each year the World Health Organization chooses strains it believes will be most likely to be prevalent in the coming year for locations around the globe. The U.S. FDA then meets to discuss the recommendations for U.S. influenza vaccine strain choice. This is how the annual flu shot is created. There are many manufacturers with different influenza products, and many influenza vaccines go through an accelerated approval process.

The chase after a flu vaccine that works has been underway for 100 years, with some of the world’s top scientists at the helm, yet we have settled for vaccines with less than 50% efficacy for the last decade.

A hundred years later, we can see similarities between the handling of the Spanish flu and covid. As with coronavirus policy, governments during the Spanish flu outbreak told citizens to isolate or social distance, wear masks, increase sanitation, and avoid mass gatherings. And, just as we saw with covid, there was a frantic rush to create a vaccine. The serious and real death toll of the 1918 influenza outbreak has been at the core of the religious fervor for a solution to stop it from occurring again.

Conclusion

The impression the Spanish flu made our collective consciousness still lives today. This terror is the root of our pandemic and influenza policies. In one way, we could say the influenza vaccine was the worst of the bunch before covid shots. It implanted the idea into our psyche that our bodies were inadequate to face the world. It sends the message that the world is a scary place and we cannot handle it with the assets endowed by our Creator.

In their book, The Truth about Contagion, Dr. Thomas Cowan and Sally Fallon Morrell put it this way, “A war on viruses is nothing more than a war on the forward evolution of humanity.” Every person and every parent of a minor child has the responsibility and right to assess the risks and benefits of the flu shot as a medical intervention: to know why it exists, why it is recommended, the risks from the illness, and the risks from the intervention. Only with that information are you equipped to decide what is best for you and for your minor children.

yogaesoteric

July 29, 2023