The Police Raids Against MISA in France, November 28, 2023. 5. The Anti-Cult Ideology in France

by Susan J. Palmer

France is unique among democratic countries in promoting a state-sponsored anti-cult ideology, based on discredited theories of “brainwashing” and “consciousness control.”

Part 5 of 5. Part 4 of 5. Read 1st part, 2nd part, 3rd part and 4th part.

To understand the charges against Bivolaru and MISA members in France, one needs to deconstruct the notion of “abus de faiblesse” within the socio-political context of the 2001 About-Picard law (often referred to as “France’s brainwashing law”). This law was passed by the National Assembly in May 2001. Its co-sponsors were centrist Senator Nicholas About and Catherine Picard, a socialist deputy in the National Assembly.

This law of 2001 was a strategical move by France’s government-sponsored anti-cult movement to control the “problem of cults.” The purpose of the 2001 law was to enable the state to prosecute “cult leaders” (labelled as “gourous” in France) who (putatively) harm their followers through the power of consciousness manipulation. This law created the new crime called “abus de faiblesse” that pointed to the exploitation of vulnerable followers by ruthless charismatic leaders of “cults,” whose influence was predicted to lead inexorably to various forms of social deviance: fraud, physical and psychological abuse, mass suicide, psychic illness, pedophilia, money laundering, and the illegal practice of medicine. Any “cult” leader found guilty of “abus frauduleux de l’état d’ignorance ou de faiblesse” (fraudulent abuse of a state of ignorance or weakness) can be liable to a five-year prison sentence and fines of up to 750,000 euros.

The first application of the 2001 law was in October 2004, when Arnaud Mussy stood on trial before the Tribunal Correctionnel of Nantes, charged with “abus de faiblesse.” As the prophet/leader of the tiny Theosophical group Néo-Phare, he was accused of “psychically manipulating” a vulnerable follower to commit suicide. Mussy was found guilty and sentenced to three years in prison (suspended) and fined 115,000 Euros.

This trial received much publicity in France, for it possessed both a legal and pedagogical value. It was a warning to all “cult leaders” to stop “brainwashing,” and to all French citizens to stop joining “les sectes.”

“Cults” are also accused of “human trafficking” as they allegedly “abuse the weakness” of their followers to make them work for free. It is well-known that voluntary labor (washing dishes and laundry, chopping carrots, or sweeping floors) is commonly practiced in Catholic monasteries (where domestic work is a kind of “worship”) and in Hindu ashrams and Buddhist sanghas (where unpaid domestic labor is understood to be “karma yoga” and is imbued with a meditative quality). It appears extraordinary that in the past decade we have witnessed a series of police raids on spiritual communes simply (or mostly) because an ex-member has complained of being forced to wash too many dishes (as in the military-style raids on Ananda Assisi in Italy, and on MISA itself in Romania in 2004, and on various spiritual communities in France and Belgium accused of “travail dissimulé”).

There are several characteristics of the legal process in “abus de faiblesse” cases that appear to undermine the principles of presumption of innocence and the impartiality of the court. First, there is the question of the authenticity and reliability of the alleged victims. It only takes one client or ex-member to file a complaint against a therapist or spiritual master at their local ADFI. This is enough to stimulate investigations and/or arrests, as an article in Le Monde pointed out. Questions have been raised concerning the personal motives of some of the self-styled “victims” and often it turns out they are overprotective parents, or jealous spouses, spurned ex-lovers, or competitive co-workers (a factor in the MISA case as well).

One serious problem for those charged with “abus de faiblesse” is that the lawyers working for the UNADFI or the MIVILUDES, have the power to file complaints on behalf of the alleged victims—without the latter’s assent, or even without their knowledge. When the so-called “victims” protest they are not victims, the court’s response is often to interpret their denial as proof of “brainwashing,” since “brainwashed” people don’t realize they are “brainwashed.” If their statements are not accepted by the court, it is the job of the Prosecutor to scrounge up additional “victims.”

In the case of the alleged “guru” Neelam Makhija’s girlfriend, she pointed out that since the police had conducted surveillance on her phone calls for over a year, the names of people who had called a wrong number to her cell and immediately hung up were included among the prospective clients who were her putative “victims”—and of course these were complete strangers she had never met or spoken to.

Finally, the “abus de faiblesse” concept relies on the highly-contested theory of “brainwashing,” called “manipulation mentale” or “emprise” in France. The concept of “brainwashing” dates back to the 1950s and its origins and plausibility as a theory has been amply documented and debated by sociologists and psychologists.

The scientific validity of the “brainwashing” theory has been questioned since it fails to pass the test of Karl Popper’s principle of falsifiability. “Brainwashing” is even one of the entries in the Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience: From Alien Abductions to Zone Therapy (New York: Facts on File, 2013, 217–18).

Although the public in various countries still embrace “brainwashing” as if it were a scientific fact that offers a straightforward psychological explanation for a person’s sudden conversion to a radical religious or political movement, since the 1980s the scientific community and the courts have discarded “brainwashing” theory as lacking in scientific rigor. The vagueness of the “brainwashing” theory, and the inherent difficulty in proving or disproving its claims puts the alleged perpetrator of “abus de faiblesse” into what one of my informants described as a “Kafkaesque” situation.

The law of 2001 is based on three “anticult” stereotypical assumptions:

1.That all “sectes” are like organized gangs or cartels: intrinsically evil and ineluctably prone to harmful and criminal activities.

2.That “gourous” tend to be manipulators who have mastered a mysterious, ineluctable technology of consciousness control/ coercive persuasion/ “brainwashing”—which they rely on to convert, control, and exploit their followers.

3.All “cult members,” due to their “brainwashed” state, are “vulnerable,” weak, and psychologically helpless, and therefore cannot be held accountable for their regrettable decisions—hence they need to be protected by the state.

It is important to be aware of the social and political context of the law of 2001. It emerged out of the anti-cult activism of France’s state-sponsored “antisectes” movement, which established a series of interministerial missions at the highest level of government, whose stated mandate was “la lutte contre les sectes,” “fighting cults.” Hence, one finds a strong bias against new alternative religions written into the About-Picard law. The amendments the government introduced in 2023, creating yet another new crime of “psychological subjection” in addition to the “abuse of weakness,” the difference being that one can become a victim of “psychological subjection” without being in a situation of “weakness,” signal the willingness to make the “fight against cults” even tougher.

However, the new provisions will not be applicable retroactively to Bivolaru. His case is yet another application of the About-Picard law in France’s “war against the ‘sectes’” and it points to a growing tendency to frame, psychologize, and criminalize the guru-chela (master-disciple) relationship, a venerable Hindu tradition, as an “abuse of weakness.”

The complex legal history of Bivolaru that spans forty years and extends across seven countries has been documented in book-length studies of MISA by Gabriel Andreescu and Massimo Introvigne and has not been recounted in this series. However, these studies make it clear that allegations of rape, prostitution, human trafficking, so eagerly broadcast in the media, have not been supported by the Supreme Court of Sweden in 2005, the European Court of Human Rights in 2014, 2016, 2017, and the Romanian courts themselves. Moreover, the charges against Bivolaru in Finland are based on theories of “brainwashing” that have been rejected as pseudoscientific in other jurisdictions.

It appears that France has taken up these old allegations based on the complaints of female apostates and crafted a new, “only in France” case against MISA’s “gourou” in which nebulous notions of “abus de faiblesse” and “dérives sectaires” clash with esoteric concepts of sacred eroticism.

Why is MISA so controversial? Introvigne suggests that there is one “red line” that, in most societies, should not be crossed; that “religion and eroticism should not be offered together.”

**********

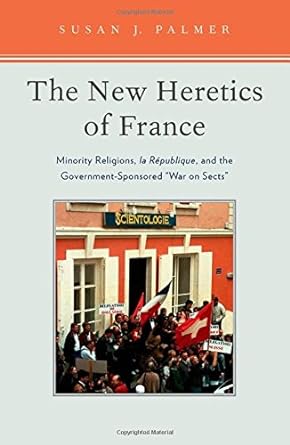

About the author

Susan J. Palmer is an Affiliate Professor in the Religions and Cultures Department at Concordia University in Montreal. She is also directing the Children on Sectarian Religions and State Control project at McGill University, supported by the Social Sciences and the Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). She is the author of twelve books, notably The New Heretics of France (Oxford University Press, 2012).

yogaesoteric

March 17, 2024

Also available in:

Română

Română