Google’s Earth: How the tech giant is helping the deep state spy on us (2)

Read the first part of this article

Google had closed a few previous deals with intelligence agencies. In 2003, it scored a $2.1m (£1.7m) contract to outfit the National Security Agency (NSA) with a customised search solution that could scan and recognise millions of documents in 24 languages, including on-call tech support in case anything went wrong. In 2004, Google landed a search contract with the CIA. The value of the deal isn’t known, but the agency did ask Google’s permission to customise the CIA’s internal Google search page by placing the CIA’s seal in one of the Google logo’s Os. “I told our sales rep to give them the OK if they promised not to tell anyone. I didn’t want it spooking privacy advocates”, wrote Douglas Edwards, Google’s first director of marketing and brand management, in his 2011 book I’m Feeling Lucky: The Confessions of Google Employee Number 59. Deals such as these picked up pace and increased in scope after Google’s acquisition of Keyhole.

In 2006, Google Federal went on a hiring spree, snapping up managers and salespeople from the army, air force, CIA, Raytheon and Lockheed Martin. It beefed up its lobbying muscle and assembled a team of Democratic and Republican operatives.

Even as it expanded into a transnational multi-billion-dollar corporation, Google had managed to retain its geekily innocent “don’t be evil” image. So while Google’s PR team did its best to keep the company wrapped in a false aura of altruism, company executives pursued an aggressive strategy to become the Lockheed Martin of the internet age. “We’re functionally more than tripling the team each year”, Painter said in 2008. It was true. With insiders plying their trade, Google’s expansion into the world of military and intelligence contracting took off.

In 2007, it partnered with Lockheed Martin to design a visual intelligence system for the NGA that displayed US military bases in Iraq and marked out Sunni and Shia neighbourhoods in Baghdad – important information for a region that had experienced a bloody sectarian insurgency and ethnic cleansing campaign between the two groups. In 2008, Google won a contract to run the servers and search technology that powered the CIA’s Intellipedia, an intelligence database modelled after Wikipedia that was collaboratively edited by the NSA, CIA, FBI and other federal agencies. Not long after that, Google contracted with the US army to equip 50,000 soldiers with a customised suite of mobile Google services.

In 2010, as a sign of just how deeply Google had integrated with US intelligence agencies, it won an exclusive, no-bid $27m contract to provide the NGA with “geospatial visualisation services”, effectively making the company the “eyes” of America’s defence and intelligence apparatus. Competitors criticised the NGA for not opening the contract to the customary bidding process, but the agency defended its decision, saying it had no choice: it had spent years working with Google on secret and top-secret programmes to build Google Earth technology according to its needs, and could not go with any other company.

Google has been tight-lipped about the details and scope of its contracting business. It does not list this revenue in a separate column in quarterly earnings reports to investors, nor does it provide the sum to reporters. But an analysis of the federal contracting data-base maintained by the US government, combined with information gleaned from Freedom of Information Act requests and published reports on the company’s military work, reveals that Google has been doing brisk business selling Google Search, Google Earth and Google Enterprise (now known as G Suite) products to just about every major military and intelligence agency, including the state department. Sometimes Google sells directly to the government, but it also works with established contractors like Lockheed Martin and Saic (Science Applications International Corporation), a California-based intelligence mega-contractor which has so many former NSA employees working for it that it is known in the business as “NSA West”.

Google’s entry into this market makes sense. By the time Google Federal went online in 2006, the Pentagon was spending the bulk of its budget on private contractors. That year, of the $60bn US intelligence budget, 70%, or $42bn, went to corporations. That means that, although the government pays the bill, the actual work is done by Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, Boeing, Bechtel, Booz Allen Hamilton and other powerful contractors. And this isn’t just in the defence sector. By 2017, the federal government was spending $90bn a year on information technology. It’s a huge market – one in which Google seeks to maintain a strong presence. And its success has been all but guaranteed. Its products are the best in the business.

Here’s a sign of how vital Google has become to the US government: in 2010, following a disastrous intrusion into its system by what the company believes was a group of Chinese government hackers, Google entered into a secretive agreement with the NSA. “According to officials who were privy to the details of Google’s arrangements with the NSA, the company agreed to provide information about traffic on its networks in exchange for intelligence from the NSA about what it knew of foreign hackers”, wrote defence reporter Shane Harris in @War: The Rise of the Military-Internet Complex, a history of warfare. “It was a quid pro quo, information for information. And from the NSA’s perspective, information in exchange for protection.”

This made perfect sense. Google servers supplied critical services to the Pentagon, the CIA and the state department, just to name a few. It was part of the military family and essential to American society. It needed to be protected, too.

Google didn’t just work with intelligence and military agencies, but also sought to penetrate every level of society, including civilian federal agencies, cities, states, local police departments, emergency responders, hospitals, public schools and all sorts of companies and nonprofits. In 2011, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the federal agency that researches weather and the environment, switched over to Google. In 2014, the city of Boston deployed Google to run the information infrastructure for its 76,000 employees – from police officers to teachers – and even migrated its old emails to the Google cloud. The Forest Service and the Federal Highway Administration use Google Earth and Gmail.

In 2016, New York City tapped Google to install and run free Wi-Fi stations across the city. California, Nevada and Iowa, meanwhile, depend on Google for cloud computing platforms that predict and catch welfare fraud. Meanwhile, Google mediates the education of more than half of America’s public school students.

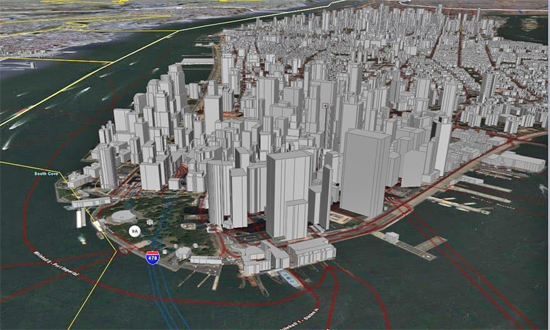

New York City mapped in an early version of Google Earth from 2006

“What we really do is allow you to aggregate, collaborate and enable”, explained Scott Ciabattari, a Google Federal sales rep, during a 2013 government contracting conference in Wyoming. He was pitching to a room full of civil servants, telling them that Google was all about getting them – intelligence analysts, commanders, government managers and police officers – access to the right information at the right time. He ran through a few examples: tracking flu outbreaks, monitoring floods and wildfires, safely serving criminal warrants, integrating surveillance cameras and face recognition systems, and even helping police officers respond to school shootings.

“We are getting this request more and more: ‘Can you help us publish all the floorplans for our school district? If there is a shooting disaster, God forbid, we want to know where things are’. Having that ability on a smartphone, being able to see that information quickly at the right time saves lives”, he said. A few months after this presentation, Ciabattari met with officials from Oakland, California to discuss how Google could help the city build its police surveillance centre.

This mixing of military, police, government, public education, business and consumer-facing systems – all funnelled through Google – continues to raise alarms. Lawyers fret over whether Gmail violates attorney-client privilege. Parents wonder what Google does with the information it collects on their kids at school. What does Google do with the data that flows through its systems? Is all of it fed into Google’s big corporate surveillance pot? What are Google’s limits and restrictions? Are there any? In response to these questions, Google offers only vague and conflicting answers.

Of course, this concern isn’t restricted to Google. Under the hood of most other internet companies we use every day are vast systems of private surveillance that, in one way or another, work with and empower the state. On a higher level, there is no real difference between Google’s relationship with the US government and that of these other companies. It is just a matter of degree. The sheer breadth and scope of Google’s technology make it a perfect stand-in for the rest of the commercial internet ecosystem.

Indeed, Google’s size and ambition make it more than a simple contractor. It is frequently an equal partner that works side by side with government agencies, using its resources and commercial dominance to bring companies with heavy military funding to market. In 2008, a private spy satellite called GeoEye-1 was launched in partnership with the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency; Google’s logo was on the launch rocket and the company secured exclusive use of the satellite’s data for use in its online mapping. Google also bought Boston Dynamics, a robotics company that made experimental robotic pack mules for the military, only to sell it off after the Pentagon determined it would not be putting these robots into active use. It has invested $100m in CrowdStrike, a major military and intelligence cyber defence contractor that, among other things, led the investigation into the alleged 2016 Russian government hacks of the Democratic National Committee. And it also runs Jigsaw, a hybrid think-tank/technology incubator aimed at leveraging internet technology to solve thorny foreign policy problems – everything from terrorism to censorship and cyber warfare.

Founded in 2010 by Eric Schmidt and Jared Cohen, a 29-year-old state department whizz-kid who served under both George W Bush and Barack Obama, Jigsaw has launched multiple projects with foreign policy and national security implications. It ran polling for the US government to help war-torn Somalia draft a new constitution, developed tools to track global arms sales, and worked with a startup funded by the state department to help people in Iran and China route around internet censorship.

It also built a platform to combat online terrorist recruitment and radicalisation, which worked by identifying Google users interested in Islamic extremist topics and diverting them to state department webpages and videos developed to dissuade people from taking that path. Google calls this the “redirect method”, a part of Cohen’s larger idea of using internet platforms to wage “digital counterinsurgency”. And, in 2012, as the civil war in Syria intensified and American support for rebel forces there increased, Jigsaw brainstormed ways it could help push Bashar al-Assad from power. Among them: a tool that visually maps high-level defections from Assad’s government, which Cohen wanted to beam into Syria as propaganda to give “confidence to the opposition”.

Jigsaw seemed to blur the line between public and corporate diplomacy, and at least one former state department official accused it of fomenting regime change in the Middle East. “Google is getting [White House] and state department support and air cover. In reality, they are doing things the CIA cannot do”, wrote Fred Burton, an executive at global intelligence platform Stratfor and a former intelligence agent at the security branch of the state department.

But Google rejected the claims of its critics. “We’re not engaged in regime change”, Eric Schmidt told Wired. “We don’t do that stuff. But if it turns out that empowering citizens with smartphones and information causes changes in their country … you know, that’s probably a good thing, don’t you think?”

Maybe they don’t “do that stuff” directly, but the people Google are more and more intimately working with are interested. And since the flow of information is controlled by Google, it can hardly be called “empowerment” if they are only allowed to see what the PTB want them to see.

Jigsaw’s work with the state department has raised eyebrows, but its function is a mere taste of the future if Google gets its way. As the company makes new deals with the NSA and continues its merger with the US security apparatus, its founders see it playing an even greater role in global society.

“The societal goal is our primary goal. We’ve always tried to say that with Google. Some of the most fundamental questions people are not thinking about … how do we organise people, how do we motivate people? It’s a really interesting problem – how do we organise our democracies?” Larry Page ruminated during a rare interview in 2014 with the Financial Times. He looked a hundred years into the future and saw Google at the centre of progress. “We could probably solve a lot of the issues we have as humans”.

yogaesoteric

February 15, 2019