Manufacturing Consent for War: 70 Years of CIA Coups, Assassinations, False Flag Operations and Mass Murder

A Review of Vijay Prashad’s book, Washington Bullets: A History of the CIA, Coups, and Assassinations, with foreword by Evo Morales (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2020).

During his confirmation hearing in February, the CIA’s latest director William J. Burns continued a long Agency tradition of playing up the threat from Russia and China along with North Korea, and said that Iran should not be allowed to get a nuclear weapon.

Vijay Prashad’s new book Washington Bullets: A History of the CIA, Coups, and Assassinations, details how manufactured foreign threats have historically been used by the Agency to carry on a war against the Third World—in order to extend U.S. corporate dominance.

In a foreword, Evo Morales Ayma, the former president of Bolivia who was deposed in a 2019 U.S.-backed coup, writes that Prashad’s book is about “bullets that assassinated democratic processes, that assassinated revolutions, and that assassinated hope.”

Prashad is a distinguished political analyst who has authored important studies of imperial interventions, corporate capitalism, and Third World political movements.

His latest book synthesizes his wealth of knowledge. It includes personal revelations of ex-CIA agents such as the late Charles Cogan, chief of the Near East and South Asia Division in the CIA’s Directorate of Operations (1979-1984), who told Prashad that in Afghanistan, the CIA had “funded the worst fellows right from the start, long before the Iranian revolution and long before the Soviet invasion.”

Washington’s Bullets starts in Guatemala with the 1954 coup that overthrew Jacobo Arbenz, whose moderate land reform program threatened the interests of the United Fruit Company.

U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles’ law firm, Sullivan & Cromwell, had represented United Fruit, and Dulles and his brother, Allen, the head of the CIA (1953-1961), were large shareholders.

The former CIA Director Walter Bedell Smith became president of United Fruit after Arbenz’ removal, and President Dwight Eisenhower’s personal secretary, Ann Whitman, was the wife of United Fruit’s publicity director, Edmund Whitman.

After the coup, Arbenz’ successor, Castillo Armas stated that “if it is necessary to turn the country into a cemetary in order to pacify it, I will not hesitate to do so.”

The CIA assisted in the bloodbath by providing Armas with lists of communists and with the gift of its assassination manual.

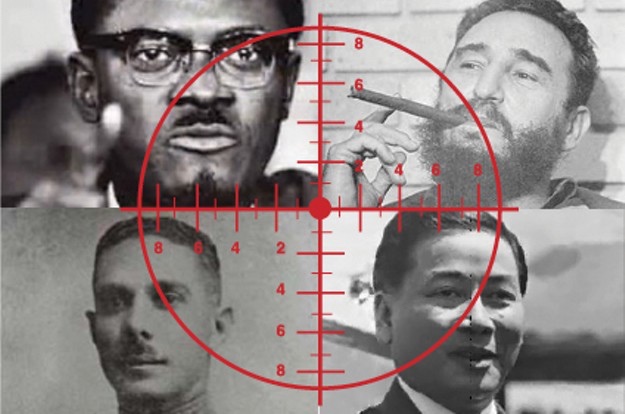

This manual was later applied in operations directed against Third World nationalists such as Patrice Lumumba of Congo (1961), Mehdi Ben Barka of Morocco (1965), Che Guevara (1967) and Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso (1987).

Sankara was killed in a plot that was carried out through close coordination between a CIA operative at the U.S. embassy in Burkino Faso and French secret service, SDECE.

According to Prashad, while “many of the assassins’ bullets have been fired by people who had their own parochial interests, petty rivalries and small-minded gains, more often than not, these have been ‘Washington’s bullets.’”

Their main purpose, he says, was to “contain the tidal wave that swept from the October Revolution of 1917 and the many waves that whipped around the world to form the anti-colonial movement.”

Prashad, as these comments indicate, roots the CIA’s crimes in the larger history of colonialism and hostility of the world’s capitalist elites to the working-class empowerment bred by the Russian revolution.

Imperialism, he reminds us, is the attempt to “subordinate people to maximize the theft of resources, labor, and wealth.”

The targets of Washington’s bullets, in turn, have been those like Sankara and many others who tried to assert their nation’s economic sovereignty.

The pattern for the CIA’s behavior was established in the immediate aftermath of World War II, when it supported political factions in Europe which collaborated with the Nazis against the communists, who had led the resistance against Nazism.

The Agency’s work, as Prashad writes, helped “bring back to life the cadaver of Europe’s reactionary political bloc.”

In Japan, this meant creating a new party (Liberal Democratic Party—LDP) to defeat the socialists that absorbed old fascists (Ichiro Hatoyama and Nobusuke Kishi) and developed enduring ties with big business and organized crime (Yoshio Kodama).

Nobusuke Kishi was a class A war criminal who later became Prime Minister of Japan because of U.S. support.

In 1953, the CIA succeeded in toppling Iran’s democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh who had moved to nationalize Iran’s oil industry.

From 1960-1965, the Agency tried to assassinate Cuban revolutionary leader Fidel Castro at least eight times by sending mafia gangsters with poison pills, poison pens, a poisoned cigar, a tuberculosis-laced scuba suit, with botulinum toxin, and other deadly bacterial powders. In total, 638 assassination attempts were made—all of them failed.

The CIA also orchestrated a coup in South Vietnam in 1963 against the Diem brothers when they sought rapprochement with the left-wing National Liberation Front (NLF).

A further coup was carried out against Indonesia’s socialist government of Achmed Sukarno, whose ouster in 1965 triggered an anticommunist bloodbath.

The 1965 Indonesian coup—like its Guatemalan and Iran predecessors and successor in Chile—followed a modus operandi involving 9 different steps:

- lobby public opinion

- appoint the right man on the ground

- make sure the Generals are ready

- make the economy scream

- diplomatic isolation

- organize mass protests

- green light

- assassination

- deny.

Perfected and refined over the years, almost all these steps have been applied most recently in the Maidan coup of 2014 in Ukraine, and right-wing coup against Evo Morales in Bolivia in 2019.

With respect to economy, Prashad unearthed an early 1950s CIA study on how to damage Guatemala’s coffee industry in order to undermine the Arbenz government.

This was a precursor to the better-known campaign by the Nixon administration to “make Chile’s economy scream” after Chileans had the audacity to elect a socialist, Salvador Allende, who nationalized Chile’s copper industry (the industry has been controlled by two U.S. corporations, Kennecott and Anaconda who lobbied for a coup).

The CIA station chief at the time of the 1973 Chilean coup, which brought the Fascist General Augusto Pinochet to power, was Henry Hecksher. He had worked underground as a coffee buyer in Guatemala at the time of the Arbenz coup and bribed Colonel Hernán Monzon Aguirre who became the leader of the junta that replaced Arbenz.

After earning promotion, Hecksher went on to spearhead CIA subversion operations in Laos and Indonesia in the late 1950s and early 1960s, before running a project against the Cuban revolution in Mexico.

Hecksher was a counterpart to sinister figures like Lincoln Gordon—a ruthless anticommunist who helped orchestrate the 1964 coup in Brazil—Marshall Green, who helped trigger the 1965 coup in Indonesia, and CIA agent Kermit Roosevelt and State Department officer Loy Henderson, who helped advance the coup against Mossadegh.

The U.S. embassy played such a direct role in coups in so many different countries that a popular joke during the Cold War held: “Why is there never a coup in the United States? Because there is no U.S. embassy there.”

One trick of the trade was the recruitment of trade union activists who could purge communists and organize strikes against leftist governments that would help facilitate their demise.

“Anything was acceptable,” Prashad writes, “to undermine the class struggle, both inside Europe and in the national liberation states.”

Prashad’s attention to class divisions offers a refreshing antidote to mainstream liberal histories of the CIA—such as Tim Weiner’s book Legacy of Ashes—which present good information but fall short in analyzing what drove the Agency’s rogue activity.

Prashad writes that “whether in Guatemala or in Indonesia, or by the 1967 Phoenix Program (or Chien dich Phung Hong) in South Vietnam, the U.S. government and its allies egged on local oligarchs and their friends in the armed forces to completely decimate the left.”

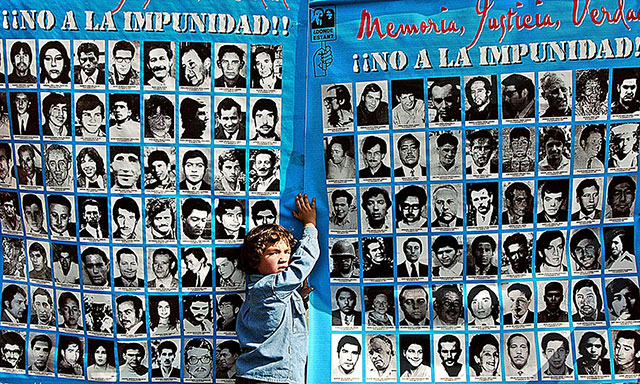

In South America, the CIA-driven Operation Condor killed around 100,000 people and imprisoned about half a million.

The CIA allied with ex-Nazi torturers like Klaus Barbie, a senior intelligence asset for General Hugo Banzer, Bolivia’s president from 1971-1978, and a key figure running Condor.

Many of Condor’s victims were proponents of liberation theology, which sought to apply the Christian gospel in support of social justice causes.

The CIA helped to kill progress in Africa by supporting such acts as the 1971 coup in Sudan by Colonel Gafar Nimiery, which deposed the communist Major Hashem al-Atta and resulted in the execution of Sudan’s Communist Party founder Abdel Khaliq Mahjub.

In the Middle East, the CIA’s crusade against communism resulted in a preference for Islamic fundamentalist like the Saudi Royal family and Pakistani General Zi-al-Huq (1978-1988), who had his predecessor Zulfaqir Ali Bhutto hanged and armed violent jihadist fundamentalists in Afghanistan to carry on the holy war against the Soviet Union.

When a Third World project emerged in the 1970s to advance the idea of a New International Economic Order (NIEO) drawing on the principle of economic nationalism, Washington worked to undermine its advancement through the delegitimization of the United Nations General Assembly, which had endorsed the NIEO in 1974.

It was in this period that the U.S. began to pressure the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to tie loans to structural adjustment programs that cut state services and were beneficial to multi-national corporations.

In the 21st century, Washington has brazenly used sanctions to try and undermine defiant governments. It has also helped manufacture corruption scandals, such as those that brought down leftists Lula and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil, whose policies had lifted almost 30 million Brazilians out of poverty.

Prashad ends his book with a quote from Otto René Castillo (1936-1967), a poet who took his notebooks with him into Guatemala’s jungles in the 1960s to fight against the U.S. imposed dictatorship. Castillo wrote:

“The most beautiful thing

For those who have fought a whole life

Is to come to the end and say;

We believed in people and life,

And life and the people

Never let us down.”

These words ought to haunt every person who has worked for the CIA; an agency on the wrong side of humanity from its inception.

In today’s increasingly authoritarian political landscape, critiques of the CIA are few and far between. Many liberals have bought into the CIA’s disinformation about Russia—particularly when Donald Trump was being accused of being a Russian agent—and lionize a President, Barack Obama, who was a major supporter of the agency.

Prashad’s book is especially important as such. With hope, it will provoke the reemergence of a movement to abolish the CIA and offshoots like the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), which is long overdue.

yogaesoteric

September 15, 2021