Petrodollar Collapse: The Invention, Rise and Fall of the Petrodollar

The word “petrodollar” doesn’t come up as much as it did before the turn of the century. However, it’s important to understand the petrodollar system because it explains how the U.S. dollar was able to retain its global reserve currency status even after defaulting on the gold standard.

What is the petrodollar?

The term “petrodollar” emerged in the 1970s to describe the new economic relationship between the U.S. and OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) that their oil exports would be priced in and sold exclusively for U.S. dollars.

You’ll sometimes see a definition like this: “U.S. dollars paid to an oil-exporting country.” That’s technically correct, but ignores historical nuance.

The origin of the petrodollar system is closely tied to three events in the early 1970s:

1. End of the Bretton-Woods System (1971): The Bretton-Woods agreement, signed in 1944, established monetary management rules for the U.K., U.S., France, Germany and 40 other countries, did two crucial acts:

- Member nations pegged their currencies to the U.S. dollar

- Guaranteed member nations could exchange dollars for gold at $35 per troy ounce

Essentially, this put everyone on the gold standard. For example, Canada (a member nation) didn’t need its own central bank gold reserve, because Canada had dollars. And dollars were convertible for gold!

The U.S. had the gold, too. At its peak, the U.S. held 651.4 million troy ounces (20,262 metric tons), or 80% of the entire world’s gold reserves!

But the good times never last. Just 27 years later, President Nixon “closed the gold window.” He broke the promise that dollars would always be convertible for gold. As you might imagine, this decision left a lot of world leaders enraged. They’d opted into the Bretton-Woods system because they believed they could swap their dollars for gold if they needed to. Suddenly, the U.S. dollar had nothing backing it.

Meanwhile…….

2. 1973 Oil Crisis: In response to U.S. support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War, OPEC stopped selling oil to the U.S. (and allied nations). The Oil Embargo sent prices skyrocketing. Crude oil prices doubled, then quadrupled. This, immediately after the dollar devaluation (a side effect of removing the dollar from the gold standard) created stagflation in the U.S.

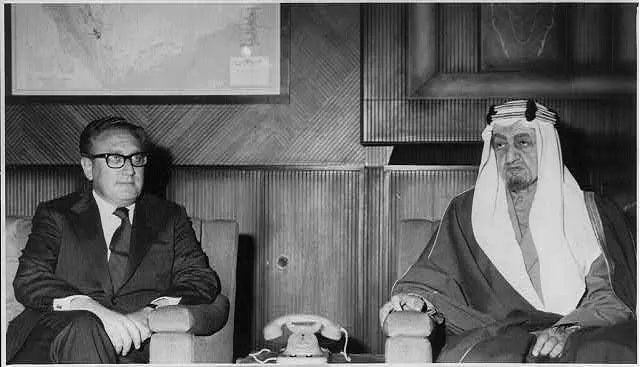

Nixon sent his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, to the Middle East. Kissinger helped negotiate a cease-fire between Israel and its adversaries (primarily Syria and Egypt but 10 other nations, including Saudi Arabia, were involved). OPEC finally lifted the oil embargo in March 1974.

It was quite clear the U.S. desperately needed:

- A friendly Arab nation in the Middle East

- A guaranteed source of oil

3. U.S.-Saudi Arabia Petrodollar Agreement: In 1973, Kissinger brokered a deal with the House of Saud. In exchange for advanced military equipment and training, along with security guarantees (“We’ll go to war if anyone invades you”), Saudi Arabia would use U.S. dollars exclusively for oil pricing and sales. Other OPEC countries followed suit by 1975, even though they didn’t get the same deal as Saudi Arabia.

Since virtually everyone in the world imported oil from OPEC, everyone in the world now needed dollars. This restored the demand for the dollar in foreign exchange markets.

This reinforced the dollar’s dominance as global reserve currency. The dollar was no longer backed by gold, but now it had a new lease on life. You could say we went from the gold standard to the black gold standard.

What is petrodollar recycling?

The Economist, in its first issue of 1974, asked “What are the Arabs going to do with it all?”

The “it” was referring to dollars, and plenty of them. Henry Kissinger had an idea.

The term “petrodollar recycling” was coined by Kissinger. He strongly suggested to King Faisal that, although Saudi Arabia could charge as much as it wanted for its oil, they should invest their surplus revenues in U.S. government debt. That is, if they wanted the U.S. to keep up its end of the security agreements.

The Saudis earned dollars for selling oil. And used those dollars to finance the U.S. government’s deficit spending. Which, as you’d expect, made government debts more affordable (which led to even more deficit spending).

The U.S. got its friendly Arab nation, an explicit guarantee that there would be global demand for dollars so long as the world ran on oil and a reliable lender for government debt.

The ruling family of Saudi Arabia got the world’s #1 superpower to guarantee their borders. (If you ever wondered why the U.S. went to war in Kuwait and Iraq back in 1990-1991, it wasn’t because of Kuwait’s oil exports. It was to make sure the Iraqis didn’t violate their 504-mile border with Saudi Arabia.)

U.S.A. kept up their end of the deal. These protestors, for example, missed the point:

Those 147 U.S. troops killed in action, and the hundreds more wounded, weren’t bleeding for oil. They went to war to preserve the dollar’s role as global reserve currency, whether they knew it or not.

The end of the petrodollar

The petrodollar monopoly on OPEC oil lasted longer than the Bretton-Woods agreement. After 45 years, Saudi Arabia broke the deal. 2018 was the first year that Saudi Arabia sold oil in another currency.

Is the petrodollar dead? Well, not exactly. OPEC nations still accept dollars for oil. Just not exclusively.

Ask instead: Is the petrodollar in trouble?

Yes, absolutely. The monopoly of dollars for oil was broken relatively recently.

The birth of the petroyuan

In 2022, Chinese leader Xi Jinping pledged to purchase more oil and gas from the Gulf, and also encouraged states in the region to conduct energy sales in the Chinese yuan.

First, simply consider that the U.S. is now a net exporter of oil. We just don’t depend so much on OPEC generally or Saudi Arabia specifically for our energy needs. While the U.S. economy has moved on, Saudi Arabia’s really hasn’t. In 2022, Saudi Arabia’s top five exports were:

- Crude oil ($236 billion)

- Refined petroleum ($45.3 billion)

- Two kinds of plastic (ethylene polymers: $13.1 billion; propylene polymers $6.4 billion) derived from petroleum

- And one industrial chemical: acyclic alcohols ($6.19 billion) also derived from petroleum

All five of Saudi Arabia’s major exports come out of the ground, either directly or indirectly. Even though their products haven’t changed, their customers have. As of 2022, Saudi Arabia’s top five buyers were:

- China ($68 billion)

- India ($46.2 billion)

- Japan ($36.5 billion)

- South Korea ($36 billion)

- United States ($23.9 billion)

China has replaced the U.S. as Saudi Arabia’s #1 customer. So when China offered to pay for oil in yuan instead of dollars, Saudi Arabia agreed. The petroyuan was born.

To be fair, the diplomatic relationship between Saudi Arabia and the U.S. has been rather strained since September 11, 2001 (15 of the 19 Al Qaeda hijackers were Saudi citizens). When the fracking boom swept the U.S. and we started exporting oil, we became competitors in the global oil market. We believe the Saudis backed the bad guys in both the Syrian Civil War and the Yemen Civil War. And every time we have a diplomatic tiff, China is standing in the background, nodding sympathetically about how unreasonable the U.S. is.

Is the petrodollar being replaced?

Not immediately, no. The majority of international trade still takes place in U.S. dollars. The petroyuan agreement with China gives that nation a sort of insurance policy against dollar weaponization efforts (like those against Russia in the wake of the Ukraine invasion). In that sense, the petroyuan deal is more of an insurance plan, a way to ensure China’s oil supply in the event NATO ever tries to lock China out of international trade.

In February 2022, NATO led by the U.S. attempted to kick the Russian government out of the global financial system. Russia’s dollar reserves were frozen, Russian banks were kicked off the international SWIFT network and companies were simply banned from doing business with Russia. The intention was to deprive Russia of oil revenue, bring the nation’s economy to its knees and bring the Ukraine war to a quick end. Russia kept selling oil, to China and India (two other BRICS member nations who are oil importers). Russia accepts payment for oil in gold, yuan or rupees. That’s not a violation of the petrodollar deal though, because even though Russia is the world’s #2 oil producer, Russia wasn’t a member of OPEC. It does point out a weakness in dollar weaponization though.

Note: A deal like this (two nations agree to exchange goods for one or the other of their own currencies, bypassing the dollar) is called a bilateral trade deal. China has lots of them.

The petroyuan would only really work for China anyway. There aren’t nearly as many yuan as dollars in circulation. The daily foreign exchange volume of dollars is 15x larger than yuan volume; which means yuan liquidity is much scarcer than dollar liquidity.

Finally, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC, China’s central bank) doesn’t let supply and demand determine the yuan’s value. Unlike the dollar, which “floats” free in global exchanges, the PBOC actively manages the yuan’s value. When the yuan appreciates, that makes China’s exports more expensive globally, which leads to reduced exports, unemployment and political unrest.

Foreign exchange is a huge and absurdly complicated topic; suffice to say the petroyuan won’t replace the petrodollar because China doesn’t want it to.

That doesn’t mean the petrodollar is secure, though.

BRICS and the petrodollar

In 2023, BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) signed a flurry of bilateral trade agreements. Talk of dedollarization among BRICS was in the air.

Russia is spearheading the development of a new currency. It is to be used for cross-border trade by the BRICS nations: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Weeks later, in Beijing, Brazil’s president, Luiz Inàcio Lula da Silva, chimed in. “Every night,” he said, he asks himself “why all countries have to base their trade on the dollar.”

BRICS nations are putting together a shared, international currency (similar to the euro) called the R5. This currency would be ideal for international trade. It could easily bypass the dollar’s global reserve status without cumbersome bilateral trade agreements. All five BRICS member nations are net exporters, which gives them the power to sell their products in whatever currency they want.

An international currency could be allowed to float, avoiding China’s worries about an overvalued yuan. The R5 would effectively bypass the dollar, solving Russia’s problems with sanctions. Although the R5 is still in development, in October 2023 the digital BRICS Pay system has created an international network.

Now, all BRICS needs to permanently dethrone the petrodollar is a shared currency. And they’re at work on that.

Author: Peter Reagan

yogaesoteric

April 4, 2024