The statistics of organ donors. A typical case of manipulation that should get all of us thinking

by Angela Anghel

The decisions we take in different situations are not based on objective criteria, nor on a measured judgment, but they are influenced by the manner in which the problem is presented to us. The way in which a question is addressed to us will influence our answer more than we could even imagine. We could make crucial decisions which contradict our interest without knowing it if we are approached in the right way. How far can these influences go? Definitely further than you can imagine.

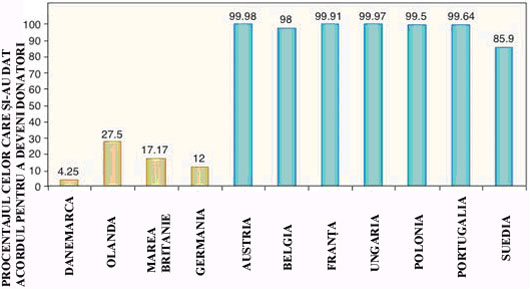

You can see in the graph below a classic example which is already famous in the study of contemporary science.

The number of organ donors of different European countries for the year 2002 is represented in this graph. To be more precise, it is the number of the people who agreed to be potential organ donors, following the completion of the forms necessary for obtaining the driver’s license. What is this about? At that time, in Europe, there was a very active interest in increasing the number of organ donors (those who agree to donate their organs upon death – an extremely sensitive subject that has more sides than presented in the official propaganda).

Where do these inexplicable differences come from?

At that time, there were a series of measures and initiatives in different European countries, and there was a series of propaganda campaigns that were conducted. One of the methods implemented in all these countries was the simplification of the procedure of enlisting on the organ donors’ lists, distinctly, the possibility of enlisting on the organ donors list upon completion of the forms necessary for getting and ID, or a driver’s license.

At that time, there were a series of measures and initiatives in different European countries, and there was a series of propaganda campaigns that were conducted. One of the methods implemented in all these countries was the simplification of the procedure of enlisting on the organ donors’ lists, distinctly, the possibility of enlisting on the organ donors list upon completion of the forms necessary for getting and ID, or a driver’s license.

In the statistics drawn up after the implementation of these measures, there were some inexplicably large differences that were noticed, in the number of organ donors in different countries. There is something suspicious about this – an amazingly large number of donors in some European countries – and a few exceptions, with a small number of donors, one of them being the United Kingdom, where there were the most campaigns for convincing the public opinion to be in favor of donating organs.

Is it that the British are not so good with propaganda, not as good as the French, the Hungarian or the Swedish? How is it possible that there’s such a huge difference between the results of some countries who have similar cultural backgrounds, standard of living and mentality, such as Belgium, the Netherlands or Denmark and Sweden? In some countries, like Germany and the United Kingdom, there was a hardened and aggressive propaganda carried out against those “lacking in humanity” who do not accept to become organ donors, systematically trying to socially stigmatize them and yet the number of organ donors was still low.

Opt-in versus opt-out. “For” or “against”

The answer comes from an entirely different direction that you might expect and is much simpler. This difference is correlated to the way the forms were made, more precisely, the way the question regarding the adhesion to the organ donor program was asked. Here are the two different versions of this same question.

The answer comes from an entirely different direction that you might expect and is much simpler. This difference is correlated to the way the forms were made, more precisely, the way the question regarding the adhesion to the organ donor program was asked. Here are the two different versions of this same question.

a) check this box if you wish to be added to the organ donor list.

b) check this box if you do not wish to be added to the organ donor list.

The a version is called “explicit consensus” in psychology – the fact that they’re asking for the approval for organ donation is clearly stated. The b version is the so called “implicit consensus” – it’s presumed that everyone agrees, as if this was already a known and perfectly legal fact and, if you do not check that box, you will be immediately placed on the donors’ list! The two versions are also called opt-in (opting to be included on the list) and respectively opt-out, opting to be excluded from the list.

Let us analyze the graph above one more time. All the countries that have that spectacular number of donors (colored blue on the graph) have used the b version of that question in the official form, and the countries with a small number of donors (colored yellow on the graph) have used the a version. Do you think this is a mere coincidence? Not at all! At that time the results of the psychological experiments in the behavioral sciences that point out the tendency of the respondents to choose the implicit answer (in other words, to leave that box unchecked) were already known. Moreover, there was a vicious propaganda for generalizing the opt-out version, the one which considers all of us as organ donors, in other countries as well, exactly because of this data.

An attentive observer might justly say that the truly neutral formulation would be the one where the problem is clearly explained and after that a YES/NO answer is required, namely the effective option for one of the two versions.

Who decides for us

The moral of this example is very simple. It is said that an informed man is worth as much as two men. We have to think if we do not want someone else to think for us. Who are the ones taking decisions for us, in cases like the one illustrated above? Obviously, our decision has already been made by the one who conceived the form and we can see this from the way the question was formulated.

The moral of this example is very simple. It is said that an informed man is worth as much as two men. We have to think if we do not want someone else to think for us. Who are the ones taking decisions for us, in cases like the one illustrated above? Obviously, our decision has already been made by the one who conceived the form and we can see this from the way the question was formulated.

Most of us have the tendency of choosing the implicit version, not just because it’s the effortless version, but also because we’re under the instinctive (and deceiving) impression that the implicit version is the normal version. The more the subject is more difficult and important, the more we’d rather bet on this implicit option.

Attention and power of discrimination, as well as a proper information process on some sensitive and important subjects should constitute the basis of our decisions and we should avoid this tendency of consensual mimicry which occurs on the stressful background of the fact that we’re obligated to make rapid radical decisions.

yogaesoteric

january 2015

Also available in:

Română

Română