Orienting Egyptian Pyramids (1)

All nine of the famous pyramids at Giza are closely aligned to true North, and the debate on how this was achieved rages on.

Solar and Stellar methods of finding Cardinal Points

The likely explanation can be achieved with both “Stellar” and “Solar” methods of alignment.

When the Egyptians were constructing their pyramids, there was no visible Pole star within two degrees of true North (the Earth’s axis is not fixed; it precesses so that the North celestial pole moves in a small circle on the sky with a 26,000-year period), yet they were able to achieve an accuracy of just three arc minutes (one twentieth of a degree). A more sophisticated explanation is clearly needed.

One possible method of aligning pyramids to true North would be the observation of two stars in simultaneous transit – that is, two stars on exact opposite sides of true North which appear to rotate around it. When they are in vertical alignment, as judged by a plumb line, their direction can be taken to be true North with a high accuracy. Because of the precession of the Earth’s axis, these two stars would have simultaneous transits only for a year or so.

The differences among the orientation of the sides of the Great Pyramid are so small that they may be explained only by the phenomenon of the precession of the equinoxes. The Pole moves to the West at a rate of 50.26 a year.

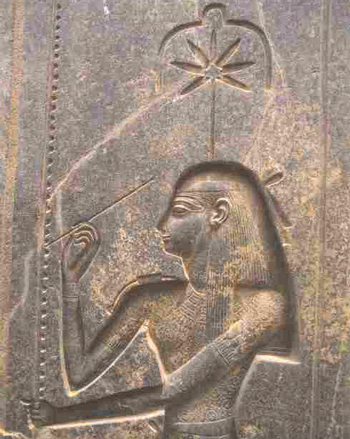

The question of the method followed in orienting the pyramids has been the object of a detailed study by Zbynek Zába. The documents prove beyond any doubt that the initial operation in erecting an important structure in Egypt was the ceremony of the “stretching of the cord,” by which through the observation of stars with some sort of transit there was determined the North-South direction. The East-West direction was marked by tracing a perpendicular to the basic line.

Zába observes that since the pyramids were oriented to the North by the observation of stars, the position of the Pole must have been obtained by bisecting the angle formed by the two extreme positions of a circumpolar star. Most scholars are of the opinion that the orientation was obtained by this procedure or by a similar one. But a few scholars have observed that a much simpler method of obtaining the northerly direction is to observe the direction of the shortest shadow of the sun at the solstices.

The bisection of the angle formed by two positions of a circumpolar star involves many possibilities of error. First of all the process of bisecting an angle exactly is difficult. Next, the process of determining which positions are opposite involves the use of clocks or an artificial line that is perfectly level. Some scholars, being aware of these possibilities of error, have suggested that there was observed the lowest culmination of a circumpolar star, which would give the North directly. But it is difficult to observe the exact point of the lowest culmination, because near this point the star moves almost horizontally; furthermore, the impact of refraction would be great in the observation of a circumpolar star at its lowest culmination, since the star would be at a narrow angle with the horizon.

The texts indicate that written instructions were followed in proceeding to “the stretching of the cord” and in drawing on the ground the outline of an important construction. Livio C. Stecchini has determined that in Mesopotamia there was a division of roles between the mathematician who planned the structure and that of the builders a similar distinction may have been made in Egypt. He suggested that, when the plan was prepared, as part of it there were performed calculations aimed at deciding which alignment of stars would give the North; the practical builders would not be concerned with astronomical problems, as they would not be concerned with the mathematical computations about the proportions of the structure, but they would simply point to specific stars according to the instructions.

If Livio C. Stecchini’s hypothesis is correct, it would follow that in the case of the Great Pyramid, the West side is at angle of 2’30” with true North because exactly three years had passed between the formulation of the project and the moment in which the area of the West side was cleared and smoothed down for the marking of the base side. A period of three and half years would have passed before the East side was ready for the corresponding operation. In the case of the Second Pyramid, the interval would be three years between the stretching of the cord on the West side and the stretching of the cord at the East side. Unfortunately, the datum about the absolute orientation of the West side, as reported by Petrie, is not entirely reliable; but if the Stecchini’s guess that the angle of the West side was 3’21” is correct, four years would have passed between the formulation of the project and the drawing of the line of the West side.

These figures not only indicate the rate of speed at which the two Pyramids were constructed, but also illuminate important astronomical issues. First of all, computing the yearly precession as 50 or 50½, all figures fit, indicating that angles could be computed within a range of approximation of 2. Father F. X. Kugler, as an expert of Mesopotamian astronomy, has claimed that the unit of 2 that occurs in cuneiform astronomical texts could not have had any concrete application, because the ancients could not have even approached such a precision in angular measures, but he has never investigated problems of ancient metrology and techniques of measurement.

Since the several measurements of the sides seem to be at intervals of years or half years, it must be concluded that the orientation was based on the movement of the sun. It can be objected that the pointing to stars does not need to wait for the occurrence of equinoxes or solstices; but it may be supposed that the planners determined the proper alignment of stars by observing the sun at the solstices, and that the operation of stretching the cord was performed at the solstices, either because this was the traditional date for orientations, or in order to control exactly the angles by computing the effect of the precession.

Creating the Ground Plan

After the primary coordinates were determined, the ground plan would be marked out. Some of the methods used to do so varied from pyramid to pyramid. Here, we examine the means by which the ground plan of the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza was determined.

Initially, a reference line along true north was constructed from the orientation process. The next step would be to create a true square with precise right angles. Within Khufu’s pyramid, there is actually a massif of natural rock jutting up that was used as part of the pyramid’s core. Therefore, measuring the diagonals of the square to check for accuracy was impossible.

Precise Right Angle

The ancient builders could have achieved a precise right angle in any of three ways:

The first method would have involved the use of an A-shaped set square. The set square would have been placed along the established orientation line and the perpendicular taken from the other leg of the square. The set square would then be flipped and the measurements repeated. The exact 90 degree angle would then be taken by taking into account the small error of the angle between the two measurements.

The problem with this method is that no set squares large enough to give a precise angle for the distances have been found in ancient Egypt. The perpendicular measurement it provides would be very short considering that the line would have to be extended some 230 meters (754 ft) in the case of Khufu’s pyramid.

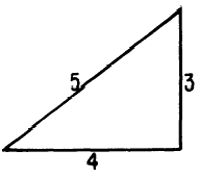

The second method would have employed the use of a sacred or Pythagorean triangle. The triangles seem to be present in the design of the Old Kingdom pyramids, but there is no real conclusive evidence of their use. Basically, this triangle uses three equal units on one side, four on the next, and five on the hypotenuse to give a true right angle.

At Khufu’s pyramid a series of holes along the orientation line are dug at seven cubit (3.675 meters or about 12 ft) intervals, so the triangle probably used these positions in the measurement. In other words, the triangle would have been measured as 21 cubits by 28 cubits with a 35 cubit hypotenuse. This would have resulted in a much longer measurement for the perpendicular line then with the use of a set square. If the unites used were any greater, the measurement would have been interrupted by the rock outcrop.

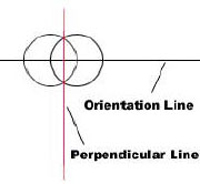

The third method possibly available to the early Egyptians would have been through the use of intersecting arcs.

In this method, two circles would have been sketched by rotating a cord around two points on the orientation line. The intersection of the two circles would then provide a right angle. Some doubt this method was used because the elasticity of the string or rope used to sketch the circles would lead to inaccuracies. However, at Khufu’s pyramid, there are a number of post holes dug that might have been used to draw such circles, so the method cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, the Egyptian may have used a rod or other device rather than rope or string to draw the circle, eliminating elasticity.

The Platform

An orientation reference line was set up in a larger square by measuring off the established square ground plan. This was done by digging post holes at measured distances from the inner square in the bedrock and inserting small posts through which a rope or string ran. These holes were dug at about 10 cubit intervals. This outer reference line was needed because the original orientation lines would be erased by building work. Various segments of the reference line could be removed so that building material could be moved into place. Then measurements were taken from the guide line as the material for the platform were put in place so that the platform was in accord with the initial floor plan.

Laying out the baseline for pyramids

The platform of Khufu’s pyramid was made of fine white Turah quality limestone slabs with occasion backing stones of local limestone for leveling. Today, we know that the platform was one of the most important elements to a pyramid’s survival over great lengths of time. It also appears that the builders of Khufu’s pyramid were well aware of this, but such knowledge seems to have been almost forgotten from time to time. Some later pyramids platforms were not built upon solid bedrock, or the platform was poorly built and those pyramids built atop these poorly constructed platforms did not survive for long.

Not only was the platform required to be laid in a perfect square, but it was also required to be very level. In Khufu’s pyramid, the platform is level to within about 2.1 cm (one inch). There were several means that this too could be accomplished. Traditional though, apparently originally conceived by Edwards, suggests the use of water to level the platform. He thought that the ancient Egyptians might have built a mud enclosure around the platform that was then filled with water. A grid of trenches would have been cut at a uniform depth below the water. However, modern Egyptologists believe this method would have been cumbersome at best. The platform would have had to have been chiseled beneath the water.

Perhaps a more accepted theory involves channels being cut to form a grid within the platform, which was then filled with water. At the top of the water’s surface, the level would be marked along the sides of the channels, and then the platform cut accordingly.

However, Lehner, who must be taken very seriously in any discussion of Giza pyramids, does not believe that water was used to level Khufu’s pyramid. In fact, he doubts any water related theories of leveling, mostly because evaporation might cause considerable variations in the measurements. Specifically though, Khufu’s pyramid is built on a sloping base, and here, it is the platform itself that is leveled and not the bedrock beneath the platform. In fact, the ancient builders were required to cut down the northwest corner of the platform, while actually building up the opposite, southeast corner.

Another leveling method might have utilized the posts used to build the reference line of the pyramid. These posts could have been made of equal heights, or marked to provide a reference level. Apparently the leveling techniques used in pyramid construction are not well understood at this time.

However, what is understood is that when the Egyptians, such as those who built Khufu’s pyramid, were at the top of their skills, the monuments they built could indeed last virtually forever.

Read the second part of the article

yogaesoteric

March 28, 2019