The Persecution and Resistance of Loic Le Ribault (II)

The creation of a treatment for arthritis and the persecution of its author, France’s foremost forensic scientist

Read the first part of the article

Directly To Jail

Although Le Ribault was “underground” in France, two of his friends suggested that he give a lecture, about G5, to a select audience. Unbeknown to him, however, with the intention of creating media interest in his case and G5, his friends had contacted the police and told them where the seminar was being held. To set Le Ribault’s mind at ease his friends told him that if the police did appear he would be whisked away, leaving sympathetic attending journalists to report the crisis. In the event Le Ribault was whisked away, however, not by his friends, but by a jubilant police posse.

Although Le Ribault was “underground” in France, two of his friends suggested that he give a lecture, about G5, to a select audience. Unbeknown to him, however, with the intention of creating media interest in his case and G5, his friends had contacted the police and told them where the seminar was being held. To set Le Ribault’s mind at ease his friends told him that if the police did appear he would be whisked away, leaving sympathetic attending journalists to report the crisis. In the event Le Ribault was whisked away, however, not by his friends, but by a jubilant police posse.

And so, by accident, the most frightening part of Le Ribault’s journey began.

“I was sent immediately to jail. I was taken first to the Bordeaux station of the Regional Crime Squad, from where the police called the judge dealing with my case, they said to him: ‘Victory, we have caught Le Ribault’.”

The judge declined to hear Le Ribault that day and he was taken to Gradignan prison.

The next day, Le Ribault was taken before the judge for a ten-minute hearing. Despite the fact that the only complaint against him was, he thought, a civil complaint from the Order of Doctors and Pharmacists, the judge ordered that Le Ribault be kept in prison. In answer to his lawyer’s protests that in the prison, he was in danger from men whom he had helped convict, the judge ruled that he be kept in solitary confinement.

What worried Le Ribault as he was taken back to the jail, was the fact that no time limit had been put on his imprisonment. The judge who was clearly “building” a case, had said only that with Christmas coming up his schedule would be full and he would not be able to hear the case. Le Ribault was also concerned that the judge who had been selected to hear his case had been one of the main customers for his forensic services when he worked for the police: a judge known throughout Bordeaux, according to Le Ribault to be “a crazy judge, very strange, very dangerous”.

Earlier on the day of his arrest, Le Ribault had five teeth extracted, now as he entered solitary confinement he was not only uncomfortable and isolated but also unable to eat. In the depths of winter, with snow falling outside and no heating inside, Le Ribault served his solitary in a cell which had next to no glass in the windows. Two fingers on one hand and both his feet became frozen and, consequently, he now has trouble walking any distance.

“The cold was the worst problem, even greater than not knowing when I would be released.”

The deprivations which Le Ribault suffered in a contemporary French prison sound echoes of Solzynitsin. As with many prisons, old systems had fallen into disuse or been adapted by the screws. Every cell had a bell in case of emergency but the guards had switched them off because of the continuous noise. To get help, the prisoners had to push a piece of paper between the door and the door jam which could be seen in the corridor. This, Le Ribault says, was “all right as long as the officers liked you”, if they didn’t, you could wait “a thousand hours”. The judge allowed Le Ribault visits from only two working colleagues, while specifically excluding his partner.

Le Ribault’s scientific imagination is also very creative. In prison, he not only recorded the day-to-day events and his thoughts, but made a number of detailed drawings of his surroundings, including the prison courtyard and his cell. Having finished these, he began meticulously copying the graffiti of other prisoners from the walls; “Some of the drawings were very good, very interesting, some poems had a lot of feeling.”

Released From Prison

At his second and last hearing before the magistrate, Le Ribault discovered that more complaints had accumulated in his file. The charges had grown from two civil complaints to include nine criminal charges, such as, the selling of a toxic substance, illegal experimentation in biology, and advertising a medicine in the press. Le Ribault was guilty of none of these further charges.

At his second and last hearing before the magistrate, Le Ribault discovered that more complaints had accumulated in his file. The charges had grown from two civil complaints to include nine criminal charges, such as, the selling of a toxic substance, illegal experimentation in biology, and advertising a medicine in the press. Le Ribault was guilty of none of these further charges.

Of the charge that he was not a doctor, Le Ribault could say only that his qualification, that of a Doctor of Science, was the highest qualification awarded by a university in France. He also made the point that any biologist and similar natural scientist who wished to emulate Pasteur, himself not a doctor, stood a good chance of being thrown in prison in modern France.

Following the arrest of Le Ribault, the authorities made a number of statements relating to G5; one, very much in his favor, was an assurance that the substance was completely not toxic.

Desperate to get La Ribault out of this nightmare backwater, his lawyer made an application to the High Court for his release.

“I was released by the High Court but the judges reserved their opinion and gave it two days after the hearing, which meant that I was an extra three days in prison. Three days in which I did not know whether I would be released.”

On his release the court imposed strict conditions on his bail, he had to surrender his passport and he was to report to the police station twice a week.

Released from prison, Le Ribault stayed first with a friend but two months after he settled there, he received a phone call from a police friend informing him that police officers were on their way to arrest him. Five minutes later, with Le Ribault watching from the garden, six police officers raided his friend’s house.

He went next to stay with another friend, a woman with whom he had been in contact while in prison. The next day Le Ribault noticed police cars observing the address. This time, he decided to make his way to Belgium.

“It took me one month to get to the Belgian border, where I was hidden in a police station by a friend who was an officer of the Gendarmerie. The policemen drove me over the Belgian frontier, using his police papers. From there I rang Belgium friends and spent four months in an isolated house in the middle of the Ardennes forest.”

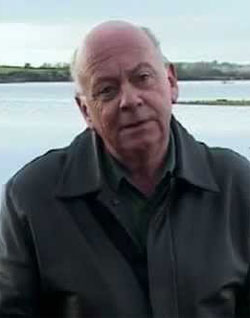

From Belgium, Le Ribault went secretly to England and from there to Jersey (Channel Islands). Later on, he fled to Ireland, where he had his own laboratory, and from there again he had to leave for other countries. In that period, he was aware of his position as man without a home or a public identity. Although he did not mention it, he had to frequently weigh up his situation in light of his early brilliant career.

“My friends have helped me because I have absolutely nothing. I have no money, no relatives. I am an illegal person, a stateless alien.”

Some Jersey Cases

Loic Le Ribault has become a medical attraction on Jersey; he has given his treatment, now called G5, to hundreds of people and although a few have found it to be ineffective for certain conditions, in the main, his clients have been satisfied. Most of those who have been treated know of Le Ribault’s deeper problems and some of them, infected by the fear which surrounds such cases do not want to be interviewed. Many others, however, were transparently behind him in his efforts to provide G5 to wider public.

Loic Le Ribault has become a medical attraction on Jersey; he has given his treatment, now called G5, to hundreds of people and although a few have found it to be ineffective for certain conditions, in the main, his clients have been satisfied. Most of those who have been treated know of Le Ribault’s deeper problems and some of them, infected by the fear which surrounds such cases do not want to be interviewed. Many others, however, were transparently behind him in his efforts to provide G5 to wider public.

Maria de Jesus is a nervous and exuberant 33 year old Maderian who has lived in Jersey for the last 22 years. Training to run 150 miles across the Sahara desert in the Marathon des Sables, she nearly broke her ankle when her foot caught in a hole.

With five weeks to go before the marathon, hospital doctors gave her crutches and told her that she would definitely not be fit for the race. She became increasingly convinced of this, when after a week and a half of concentrated physiotherapy, she was no better.

A friend suggested that she visit Le Ribault and made an appointment for her.

“My friend rang him at eight o’clock in the evening and he said come over. I told him about my ankle, he looked at it and told me that I would be able to do the race. I did not believe him and was very skeptical. I had to drink a spoonful as well as putting a poultice on my foot. I was quite frightened but I was willing to do anything in order to go on the race.”

Maria says that after taking G5 for a few days, she felt more energetic and began jogging. A week after she began the treatment, her ankle was completely healed. Three weeks later, Maria set off for Morocco where she ran the grueling one hundred and fifty mile race across the desert.

Maria has advised a number of her friends to use 0S5 and to see Le Ribault and says that from these people, she has not had a single complaint.

“This is a treatment with absolutely no adverse side effects and it should be freely available to people.”

Frank Amy is a tough, level headed, skeptical working-class man, who has had a crumbling spine for the last eighteen years. Initially it was Le Ribault who contacted Amy, wanting him to help in introducing G5 to the Island. After his first meeting with Le Ribault, Ames read the case histories of other treatments and felt complete disbelief.

Amy, who had been on strong pharmaceutical pain killers for eight years, was sleeping only from two to five hours a night because of discomfort and pain but what really upset him was that he was unable to bend enough to tie his shoe laces. After his first meeting with Le Ribault in November 1997, Amy began treating himself with G5.

Feeling that it was important “to be fair to the treatment” Amy stopped taking his expensive pain killers. Within a fortnight of taking the treatment he was feeling and sleeping better; some nights he was sleeping for eight hours. Within a month he could bend down to tie his shoe laces. Amy took G5 for ten weeks. Seven months after the treatment, when he was interviewed, he said he still feels very well and he is almost able to touch his toes without the slightest pain. Apart from the continuing problem of a crumbling spine and occasional painful twinges which he puts down to sensitive nerves, he considers himself cured.

Since his experience with G5, Frank Amy has become the distributor of the therapy on Jersey. As Head Constable of his elected Parish police, one of twelve on Jersey, Amy is in charge of licensing; he also sits in the State’s Parliament. With these duties, he felt a certain responsibility for Le Ribault and his therapy, he also felt that it was important to get proper legal status for him and a specially built clinic. Amy suggested that his full time post as Head Constable, a little like an English Mayor means that he should “assist the people as much as possible” . He saw the possibility of help being extended to Le Ribault because he is in effect a businessman, and to his parishioners who might gain from his treatment. Sitting in the State’s Parliament, Amy also keeps a weather eye on the island’s drugs bill and can see evident savings if G5 were to be used more widely.

Paul Leverdier is a 40 old pool technician for the Jersey General Hospital, a carefully spoken triathlon athlete who works with patients in the hospital pool. In early 1998 he suffered with chronic Achilles tendonitis, a painful tightening and jamming of the Achilles tendon often caused by overtraining.

Laverdier’s tendonitis had lasted for six months and was badly affecting the running and cycling aspects of his triathlon events. A physiotherapist colleague at the hospital had tried to treat the condition with ultra sound and frictions (a massaging of the tendon). After six months, the problem had been going on for so long that Leverdier began to think that he would reluctantly have to take long-term rest.

After Laverdier was introduced to Le Ribault, he put SO5 on a tissue, taped it to the back of his ankle and left it overnight. Previously, when he went running, the pain on starting to run and speeding up had been crippling. The morning after he treated himself, there was no pain and, when he had finished, the tendon was not jammed up with heavy mucus as it had been in the past. He continued with the treatment for two more consecutive nights, now treating both tendons. Five months after the treatment, when he was interviewed, Laverdier seemed to have shaken off the tendonitis completely and was turning in triathlon times which he would have been proud of five years earlier.

Laverdier had not told his colleagues at work about his self-medication; he would, he says, be embarrassed by their skepticism.

The Meaning Of A Story

Dr. Loic Le Ribault’s story reads in part like a movie in which the boffin-like scientist, after some hocus pocus in the laboratory, discovers a ‘cure-all elixir’ and is then hounded, chemical flask in hand, by men in black hats. From another perspective, however, his story reads in shades of the darkest noire, a synthesis of classic contemporary dramas, in which the publicly concerned scientist finds himself, like Ibsen’s character, in An Enemy of the People, beyond the pale of the orthodox community, branded as a fraud and a charlatan and hounded by the furies of profit and power.

Dr. Loic Le Ribault’s story reads in part like a movie in which the boffin-like scientist, after some hocus pocus in the laboratory, discovers a ‘cure-all elixir’ and is then hounded, chemical flask in hand, by men in black hats. From another perspective, however, his story reads in shades of the darkest noire, a synthesis of classic contemporary dramas, in which the publicly concerned scientist finds himself, like Ibsen’s character, in An Enemy of the People, beyond the pale of the orthodox community, branded as a fraud and a charlatan and hounded by the furies of profit and power.

However we read the tale, we might recognize it as a once apocryphal story which is fast becoming an everyday reality. The scientist, medical scientist or doctor, forced to work beyond orthodoxy and subjected to powerful manipulation, ridicule, sabotage or criminalization, is becoming an increasingly common figure in contemporary drama and real life.

Although the ethnic or national details of these histories of scientific dissent, whether their subject be BSE, Vitamin B6, G5, cold fusion, homoeopathy or everlasting light bulbs, differ slightly, they are all Euro-American stories of the post-modern era. Le Ribault’s case, that of a well-established scientist living on an independently governed island, in exile from a European, apparently democratic, power and owning a medicinal product which is legally produced and distributed across the world, illustrates the international nature of the condition.

It would be theoretically attractive to describe a temporal and social continuum for dissident scientists, beginning with the resurgence of science as a powerful ideology in the post-industrial period. In fact, the struggle between science and the ideological establishment and within science between its ruling groups and its dissidents, has changed little in quality, since the time of Galileo who was tortured by the Catholic Church for claiming that the Earth revolved around the Sun.

It seems possible, however, that a century ago, or even fifty years ago, Le Ribault’s work, pursued only out of a pure and curious interest in science and health, might have been supported by the State or by philanthropists and the results of his work offered by some commercial organization to the people. In post-industrial Europe and France particularly, ‘the public’ no longer has a voice at powerful tables. Today the remarkable discovery of Loic Le Ribault and Norbert Duffault, which is indisputably in the interests of the public, has become the carrion for the wolves of private, vested interests.

In an era when the market, especially in medicine, is fought over by multinational corporations and manipulated by huge trading blocs, Le Ribault’s path is an increasingly well-trodden one. The metropolitan centers of orthodox industrial science are now fringed by dissidents: intellectual ‘travelers’ who are as surely banished as the religious heretics who wandered medieval Europe.

In the post-modern era, vested commercial interests regulate both science and medicine and more than ever before the leading institutions of the scientific and medical professions are in the pockets of industry. This free-for-all between science, professional dogmatism and vested interests was most colorfully displayed during the years which followed Robert Gallo’s ‘discovery’ that the probable cause of AIDS was HIV.

For those who take an interest in dissent within science, the year 1985 is recognizable as the point at which scientific work began to be reviewed by press conference rather than peers groups. In France, in the years that the Wellcome Foundation protected its monopoly license for AZT, a number of medical research scientists found themselves facing the possibility of criminal charges, for perusing their own scientific investigations of AIDS related illness. In both Britain and America, scientists who failed to concur with the viral model of AIDS-related illness were frozen out of their work and their funding withdrawn.

When Le Ribault and Professor Duffaut applied to have G5 tested on people with AIDS-related illnesses, in 1987, the Wellcome Foundation had, weeks before, gained its monopoly license to market AZT. This initial licensing in Britain and America, which had been received only six months after Phase II trials for the drug had been aborted, was followed by a multi-million dollar campaign across the world, beseeching governments to buy. In 1989, for example, the Brazilian government paid $130 million for AZT. France bought into AZT within a matter of weeks of it being licensed.

It was clear from the amount of money which Wellcome pumped into professional committees, advertising and ongoing research into AZT, that when a country bought AZT, it was also expected to cease research on any other approach to the problem of Aids- related illnesses. In America and other European countries, non-pharmaceutical and specifically non anti-viral approaches to AIDS, were discouraged.

The other ailments for which G5 has proved most effective, rather than speculative, have been inflammatory illnesses like arthritis and injuries such as muscle strains. These are all highly competitive areas of profit for the pharmaceutical industry.

If Ribault’s case is anything to go by, the French, like the Americans, appear to have a very demonstrative way of resolving their battles over science. While the British tend to be fair and transparent in theory, while secretly smudging decisions in practice, the French take their recalcitrant scientists to court or throw them in prison, while at the same time silencing the press.

If Ribault’s case is anything to go by, the French, like the Americans, appear to have a very demonstrative way of resolving their battles over science. While the British tend to be fair and transparent in theory, while secretly smudging decisions in practice, the French take their recalcitrant scientists to court or throw them in prison, while at the same time silencing the press.

In Italy, patients and cancer doctors have been publicly divided by the unorthodox vitamin and hormone treatment developed by Professor Luigi Di Bella. But there, as is often the case in Italy, the people have taken to the streets to express their views, turning choice in medicine into a fundamentally political issue, related to concepts of democracy as well as science.

In America and Canada, countless physicians and research scientists working especially in the field of innovative cancer treatments have been pushed over the national boundaries, into Mexico or to off-shore islands like the Bahamas. During the early nineties, a number of medicinal plants practitioners were sent to prison for contravening the laws which govern the use and prescription of medicinal plants. Throughout the eighties and nineties, numerous practitioners have been brought before professional disciplinary panels for practicing alternative or complementary medicine. In 1995, armed FDA officers, in search of B vitamin complexes, raided the laboratory and offices of one of America’s leading nutritional doctors, Jonathan Wright. Clinic workers were made to raise their hands and stand against the wall, while officers pointed guns at them. It took the agents, with the help of police, fourteen hours to strip the clinic of all equipment and its vitamin and food supplement stocks.

In 1989, a French Canadian scientist and pioneer of microscopy, Gaston Naessens, was put on trial in Quebec. After 40 years research, Naessens had concluded that it was possible to diagnose cancer by observing the life-history of micro-organisms in the blood. The Canadian government and the medical establishment indicted Naessens on charges of manslaughter as well as the illegal practice of medicine. More recently, another French Canadian, medical doctor Dr. Guylaine Lanctot resigned from the Royal College of Canadian Physicians, rather than stand disciplinary trial over her position on vaccination and what she had termed The Medical Mafia, in her book of that name.

In Britain, in 1990, powerful individuals within orthodox medicine and medical science, tried to shut down the Bristol Cancer Help Centre. They gave world-wide publicity to bogus research results claiming that anyone going to the Centre was three times more likely to die of cancer than someone who sought orthodox help. In 1997, vested interests in science and the pharmaceutical industry managed to persuade the new Labor government that the sale of vitamin B6, particularly useful in cases of stress and hormonal problems in women, should be restricted.

Because the power of today’s corporations is so awesome, there are fewer and fewer people willing to fight the corner for the Loic Le Ribaults of the world, disparaged or criminalized by the system. This lack of popular defense for those who argue the public interest is a sad reflection on European democracy. Although the voice of the dissident has always been with us, the wilderness into which that voice now sounds has radically changed in the post-industrial era. Dissidents are no longer popular figures as they were in the nineteen fifties and sixties.

Le Ribault had harsh words for the French public, who he felt must have known of his circumstances but did nothing.

“I have cured maybe 20,000 patients and there are now many doctors using G5. Everyone in France knew that I was put in jail, many of my patients knew that I was in jail. Yet I received only 30 letters. Even about such an important problem as their own health, French people unfortunately do not act together. I keep remembering that during the Second World War, many of them were like sheep and numerous people in authority collaborated with the enemy. Only a very few dared make any resistance. I have lost everything to help people, now the patients have to fight if they want the cure. They have to ask for the right to use the medicines they want.”

Le Ribault saw the patients right to choose as being the salient right in the dispute between himself and the French State. In arriving at this conclusion, he had much in common with those on the American Right who are demanding the breakup of big regulatory government and protective professional cartels.

“One point of great weight”Le Ribault said, “seems to have been forgotten in this whole affair. It is not the medical authorities who should be deciding the fate of sick people. It is for the sick themselves and only the sick to make such decisions.”

Le Ribault had survived his ordeal – until his death, at age 60 – with his sense of humor remarkably intact and his mental and moral faculties well-balanced. He wrote a 521 page book entitled The Cost of a Discovery – Letter to my Judge (Le prix d’une découverte – Lettre à mon juge) . The book bears no resemblance at all to The History of a Grain of Sand,the major work of his intellectual youth. This book is a gauntlet thrown at the feet of the French establishment, studded with the names, addresses and telephone numbers of those in the judicial and policing establishment who brought about his downfall. It reads like a handbook for intellectual guerilla warfare. Although Le Ribault held out little hope in this respect, and had, anyway, little desire for his political and social resurrection in France, he did want to force the French establishment, the police and the judiciary in particular, to face their crimes.

Le Ribault had survived his ordeal – until his death, at age 60 – with his sense of humor remarkably intact and his mental and moral faculties well-balanced. He wrote a 521 page book entitled The Cost of a Discovery – Letter to my Judge (Le prix d’une découverte – Lettre à mon juge) . The book bears no resemblance at all to The History of a Grain of Sand,the major work of his intellectual youth. This book is a gauntlet thrown at the feet of the French establishment, studded with the names, addresses and telephone numbers of those in the judicial and policing establishment who brought about his downfall. It reads like a handbook for intellectual guerilla warfare. Although Le Ribault held out little hope in this respect, and had, anyway, little desire for his political and social resurrection in France, he did want to force the French establishment, the police and the judiciary in particular, to face their crimes.

If Letter to my Judge fails to stir the conscience of the French Republic, then Le Ribault hoped that his case, which went before the European Court of Human Rights and involving thirty-seven charges against the French authorities, will at least send a public signal to those who have tried to destroy him. However, his case was thrown out summarily by the EU Court of Human Rights. Thrown out, after six years of process, with an accompanying message that they would “not reply to any further communications with your lawyers”.

His struggle has turned Le Ribault into a political radical; he says ironically, that although he has never had anything to do with French politics, his next book could well be about revolution.

On a personal level, Le Ribault became frustrated with his virtual house arrest in Jersey. Despite the fact that the authorities have acted with understanding and the locals with empathy, and although he had plans to set up a clinic there, he also felt the call of his newly-adopted Antigua. He hoped in time to reclaim his possessions, his books and papers, from France, and begin a new life of retirement working on his molecule and fishing in the warm clear seas around the island.

His principal regret, he said laconically, was “not that I have this story to tell, but that such a story should have to be told in modern France.” Asked if he is sad that he could not return to France, Le Ribault was definite: “I never” he said, slowly, “wish to set my foot on France soil again… ever. Perhaps to see the graves of my parents, for a moment I would go back ” he adds, “but then come away again. I consider now that I was before a citizen of Brittany and not of France.” He could hardly contain his anger: “I have been told by the police that if I am in France again, I would not just be arrested but killed. I hate France” he said softly.

By the time he went in his exile in Jersey, Le Ribault felt that he has done all he was personally able to do with G5: “I have agents in many countries and about 100 doctors and practitioners now using G5. I receive calls from new doctors every day, there is a lot of interest in France, Belgium, Ireland, Switzerland and Portugal. I have the task of improving the molecule, it is doctors that should be treating people. The production of G5 is in France, it is legal and it is non-toxic and it is to high standards.”

Le Ribault was angry and perturbed that the French government did not take the discovery from him and Norbert Duffaut, taken over its production and introduced it to the world as an accepted international medicine.

“But” he said, “It is not the government who are in control of the country, but the multinational corporations and the financial people, my struggle is evidence of that.”

yogaesoteric

March 31, 2017

Also available in:

Română

Română