Agarttha: Taking the Lid Off the Underground Kingdom

By Alexander Light

In 1884 the French occultist Saint-Yves d’Alveydre

(1842-1909) decided to take lessons in Sanskrit. Having just published his definitive work on

the secret history of the world, called Mission des Juifs (“Mission of the

Jews”), he was anxious to deepen his understanding of the sacred languages which, he

felt sure, concealed the ultimate mysteries.

Hebrew had already revealed much to him; now it was time to

tackle the even more ancient language of Sanskrit, parent of all the Indo-European

tongues.

Saint-Yves’ Sanskrit teacher, who called himself

Hardjji Scharipf, was a character of hazy origins and the subject of various rumours. Born on

December 25, 1838, he supposedly left India after the Mutiny of 1857 and set up in the French

port of Le Havre as a bird-seller and professor of Oriental languages.

His name may have been a pseudonym; he may have been an

Afghan; some called him Prince. But whatever his story, the manuscripts now in the Library of

the Sorbonne in Paris show that Hardjji was a learned and punctilious teacher, and the source of

two still unsolved enigmas: the underground kingdom of Agarttha, and its sacred language.

Three times a week, Hardjji would come to Saint-Yves’

luxurious home with a beautifully scripted lesson of grammar and a reading from some Sanskrit

classic. But his diligent pupil became more and more fascinated by Hardjji’s mysterious

hints, which began when he signed the very first lesson as “Teacher and Professor of

the Great Agartthian School.”

Saint-Yves must have asked him what this “Great

Agartthian School” was. He might already have read in the books of the popular travel

writer and historian Louis Jacolliot of an “Asgartha,” supposedly a great city of

the ancient Indian priest-kings, the Brahmatras. Does such a place still exist, then?

Apparently Hardjji made him to believe so, and, what is more,

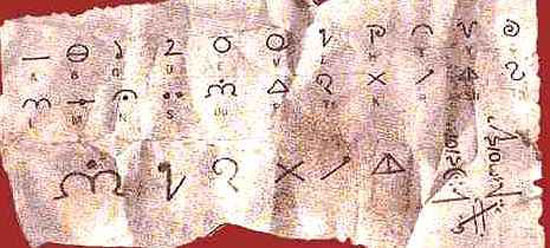

that it preserves a language and a script known as “Vattan” or

“Vattanian,” that are the primordial ones of mankind. For someone in quest

of the secret and sacred roots of language, the mention of such things must have been unbearably

exciting.

Curiosity overcame him on Christmas Day, 1885, when he asked

Hardjji to write out his own name in Vattanian characters. The guru obliged, writing it on the

back of the lesson sheet and adding wryly: “Here, according to your ardent desire; but

really you are not yet sufficiently prepared for Vattan. Slowly and surely!”

Later he must have taught Saint-Yves the Vattanian alphabet

and the principles behind its 22 letter-forms, which Saint-Yves would correlate with the Hebrew

alphabet and with the zodiacal and planetary symbols.

By the end of the course of lessons, Agarttha and Vattanian

had evidently become regular topics of conversation, while Saint-Yves’ interests shifted

from Sanskrit to a kind of comparative Hermeticism. With Hardjji’s approval, he created a

splendid manuscript in red and gold ink containing invocations, sigils, many alphabets, designs

and arabesques made from Sanskrit and Vattanian letters; a list of Vedic and Biblical names

encoded in a so-called “Hermetic or Raphaelic Alphabet”; eighty Vedic

symbols representing the development of the cosmos; a passage on the “Hermetic

Significance of the Zodiac” encoded in planet and zodiac signs; correlations of these

signs with the names of angels and with Vattanian, Sanskrit, Hebrew, and Hermetic characters;

breathing exercises for the hearing of the inner sound “M” and for soul-travel;

notes on the properties of medicinal plants; alchemical recipes.

Saint-Yves Writes a Book About

Agarttha

And this was not all. Did Hardjji know that Saint-Yves was

writing another book – The Kingdom of Agarttha: A Journey into the Hollow Earth

– under the influence of his Oriental studies? It seems doubtful, but in 1886 the book was

finished, typeset, and printed by his regular publisher (Calmann Lévy).

To put it bluntly, this book takes the lid off Agarttha. The

reader will learn that it is a hidden land somewhere in the East, beneath the surface of the

Earth, where a population of millions is ruled by a Sovereign Pontiff, the

“Brahatmah,” and his two colleagues the “Mahatma” and the

“Mahanga.”

This realm, Saint-Yves explains, was transferred underground

and concealed from the surface-dwellers at the start of the Kali Yuga (the present dark age in

the Hindu system of chronology), which he dates to about 3,200 BC. Agarttha has long enjoyed the

benefits of a technology advanced far beyond our own, including gas lighting, railways, and air

travel.

Its government is the ideal one of “Synarchy,”

which the surface races have lost ever since the schism that broke the Universal Empire in the

fourth millennium BC, and which Moses, Jesus, and Saint-Yves strove to restore. (This was the

theme of Mission des Juifs.)

Now and then Agarttha sends emissaries to the upper world, of

which it has a perfect knowledge. Not only the latest discoveries of modern man, but the whole

wisdom of the ages is enshrined in its libraries, engraved on stone in Vattanian

characters.

Among its secrets are those of the true relationship of body

to soul, and the means to keep departed souls in communication with the living. When our world

adopts Synarchical government, the time will be ripe for Agarttha to reveal itself, to our great

spiritual and practical advantage.

In order to speed this process, Saint-Yves includes in the

book open letters to Queen Victoria, Emperor Alexander III of Russia, and Pope Leo III, inviting

them to join in the great project.

Perhaps the oddest thing about this book is Saint-Yves’

own stance. Far from presenting himself as an authorised spokesman for Agarttha, he admits that

he is a spy.

Dedicating the book to the Sovereign Pontiff and signing it

with his own name in Vattanian characters (just as Hardjji had written it out for him), he

expatiates on how astounded this august dignitary will be to read the work, wondering how human

eyes could have penetrated the innermost sanctuaries of his realm.

Saint-Yves explains that he is a “spontaneous

initiate,” bound by no oath of secrecy, and that once the Brahatmah gets over the

shock, he will admit the wisdom of what Saint-Yves has dared to reveal.

How did Saint-Yves obtain this information? Already in his

first book, Clefs de l’Orient (1877), he was writing with the confidence of an

eyewitness of the psychic phenomena accompanying birth, death, and the relation between the

sexes.

In the present work he seems to have extended his psychic

vision, to say the least, and one can glean from here and there an idea of his methods.

There is, for instance, a passage here describing in detail

how the Agartthian initiates travel with their souls while their bodies sleep. Then there is the

passage in the notebook already mentioned, on yogic exercises for separating the soul from the

body. Thirdly, there is a snippet of occult gossip in a conversation with Saint-Yves recorded on

August 16, 1896, by a psychical researcher, Alfred Erny: “He has talked to Papus and

[Stanislas de] Guaïta, but did not tell them what they wanted to know: the method of

disengaging and re-engaging oneself in the astral body. It is dangerous: ‘I don’t

want (he said) to put a loaded revolver into your hands which you don’t know how to

use.’

‘A magnetiser’, he said, ‘runs less

danger than others in duplicating himself, because he is more trained.’

‘When one goes out of one’s body into the

Astral, another evil spirit may replace you’.”

Saint-Yves presumably possessed the secret of this

“somnambulistic” faculty, and used it to gather the information he presents in this

book. But did he gather it, as he claims, from spying on a physical Agarttha beneath the surface

of the Earth? Or was it the result of his own projected fantasies or hallucinations?

Or, again, did it come from some non-physical location or

state which can be accessed under certain conditions, but which then merely supports the

psyche’s own subjective expectations and prejudices? We will return to these questions at

the end.

No sooner was the book printed and ready for the bookshops

than Saint-Yves withdrew it, destroying every copy but one. The work narrowly escaped oblivion,

but this one copy passed after Saint-Yves’ death to Papus, who published it in 1910, with

some omissions, under the auspices of a group of disciples, the “Friends of Saint-

Yves.”

Decades later, it turned out that the printer, Lahure, had

secreted another copy. The late Jean Saunier, biographer and chief authority on Saint-Yves, used

this as the basis for the complete French edition of 1981, now translated into English.

Whatever reasons and motives were responsible for the sudden

withdrawal of the book, there is no doubt that Saint-Yves remained true to his vision. For

instance, he mentions Agarttha and names its three rulers in his epic poem of 1890, Jeanne

d’Arc victorieuse.

Saint-Yves d’Alveydre

In his conversations with Erny in 1896, he stated outright

that there exists a secret “Superior University” with a “High

Priest” who is currently an Ethiopian, and other details just as they appear in this

book. Finally, he mentions Agarttha in veiled terms in L’Archéomètre, the major

work of his last years.

Ossendowski Revives

“Agharti”

After the trauma of World War I, the very name of Agarttha

might have been forgotten, as Saint-Yves himself was. But in 1922, a Polish

“scientist” named Ferdinand Ossendowski (1876-1945) published a sensational travel

and adventure book.

It told of his flight through Central Asia in the aftermath

of the Russian Revolution. While in Mongolia, he heard tell of a subterranean realm of

800,000,000 inhabitants called “Agharti”; of its triple spiritual authority

“Brahytma, the King of the World,” “Mahytma,” and

“Mahynga,” of its sacred language, “Vattanan,” and

many other things that corroborate Saint-Yves.

The book ended on a dramatic note of prophecy from one of

Ossendowski’s informants: that in the year 2029, the people of “Aghardi” will

issue forth from their caverns and appear on the surface of the Earth.

The prophecy was attributed to the King of the World when he

appeared before the lamas in 1890. The King had then predicted that there would be 50 years of

strife and misery, 71 years of happiness under three great kingdoms, then an 18-year war, before

the appearance of the Agarthians.

An unprejudiced reader, finding in three chapters of

Ossendowski’s book a virtual outline of Saint-Yves’ Agarttha, not omitting the most

improbable details, would conclude that the author had capped an already good story with a

convenient piece of plagiarism, altering the spellings so as to make his version, if challenged,

seem informed from an independent source.

At first Ossendowski denied this indignantly. When he was

introduced to the esotericist René Guénon (1886-1951), he said that if it were not for

the evidence of the daily journal he had kept, and of certain objects he had brought back, he

would have thought that he had dreamed parts of this story, adding: “I’d much

prefer that!”

Back in 1908, the young Guénon had taken part in

automatic writing séances in which Agartthian matters had come up, though whether through

the questioners or the channelled entity is now unclear.

Now his interest was rekindled, and in 1925 he wrote about

the striking parallels between Saint-Yves’ Agarttha and the Agharti of Ossendowki, whose

sincerity, according to Guénon, there was no reason to doubt.

Two years later, Guénon took the matter into his own

hands. In his most controversial book, Le Roi du Monde, he announced:

“Independently of the evidence offered by Ossendowski, we know from other sources that

stories of this kind are widely current in Mongolia and throughout Central Asia, and we can add

that there is something similar in the traditions of most peoples.”

Unfortunately Guénon does not support his claim to

privileged access by telling us what these sources are, nor what degree of similitude is meant

by “stories of this kind.”

Near the end of Le Roi du Monde, Guénon faces the

question of whether Agarttha really exists: “Should its setting in a definite location

now imply that this is literally so, or is it only a symbol, or is it both at the same time? The

simple answer is that both geographical and historical facts possess a symbolic validity that in

no way detracts from their being facts, but that actually, beyond the obvious reality, gives

them a higher significance.”

So Guénon at the very least did not deny a geographical

Agarttha. To his way of thinking, if one were found to exist beneath the surface of the Earth,

it would only corroborate the superior reality of the symbolic one.

Ossendowski’s account was later investigated by Marco

Pallis (1895-1985), the traveller, writer on Buddhism, and translator of Guénon, with the

advantage of his own contacts with highly-placed Indians, Tibetans, and Mongolians. One of the

latter, now very old, had been the head lama of a monastery at the time of Ossendowski’s

visit there.

Marco Pallis

He testified that the latter’s stories of the King of

the World and of Agarttha bore no relation to any authentic legend or doctrine whatsoever, and

that Ossendowski’s command of the Mongolian language had not been nearly sufficient to

understand what he claimed to have heard.

Pallis’s Hindu friends, similarly, disclaimed any

Sanskrit source for Agarttha. The inevitable conclusion was that the credulous Guénon had

been misled by Saint-Yves’ fantasy, and that promoting belief in Agarttha in Le Roi du

Monde had been a foolish mistake.

Ossendowski himself had back-pedalled in November 1924 when

pressed to appear before a group of prominent intellectuals and scholars. He confessed to this

hard-boiled audience that Beasts, men and gods was not

“scientific” but “exclusively a literary work,” and

stated the same in a letter to the Royal Geographical Society.

Never mind: once his best-seller had brought the Agarttha

myth out of the esoteric closet, it began to enjoy a new lease on life.

Often confused or contrasted with Shambala, the spiritual

city of Tibetan Buddhism, it became a recurrent theme of popular occult writers.

If we set aside Saint-Yves and Ossendowski, for reasons

already explained, there remain only two independent witnesses to an Indian Agarttha tradition.

Louis Jacolliot was led to place it in the past, as the ancient Brahmanic capital. For Hardjji

Scharipf it was a living initiatic school with its own secret script.

Until a reputable scholar comes forward with data on the myth

of Agarttha, and especially on the Vattanian alphabet, my working hypothesis is that these were

part of a mythology belonging to a restricted and obscure Indian school, which has only surfaced

to Western notice on these two occasions.

However, Saint-Yves wanted more than the tantalising taste

that his Sanskrit teacher allowed him. He therefore decided to use his gift for astral travel to

explore Agarttha further, and was rewarded by visions of an underground utopia and its Sovereign

Pontiff, the spiritual Lord of the World. What is the source, and the ontological status, of

such visions?

The Astral World and Delusions of

Grandeur

There are, one gathers, definite places or complexes in the

Astral World, which present to the clairvoyant visitor certain invariable features. But the

incidental circumstances of such a place vary, according to the visitor’s own cultural

conditioning and expectations.

Some find themselves, for example, in what they believe to be

the Alexandrian Library, or in Atlantis, i.e., a place of the past. To others, it seems current

and contemporary, though preferably in an inaccessible location like the Himalayas.

The décor is a trivial matter, of course, in comparison

to the philosophical truths to be discovered there, but the glamour of it sometimes overwhelms

the traveller. Then his attention fixates on irrelevant details, and an inflated sense of self-

importance may result.

Thus Saint-Yves, convinced that he has penetrated to the

realm of the world’s spiritual ruler, writes about four-eyed tortoises, two-tongued men,

levitating yogis, and ends up addressing pompous letters to Queen, Emperor, and Pope.

I can accept that in some state of altered consciousness he

saw what he claims to have seen. But like many who habitually indulge in altered states, he was

not able to situate his visions, nor himself as witness to them, with the requisite

philosophical detachment. The result is a classic case of the occupational hazard of occultists:

misplaced concretism.

Yet there is a grandeur to this book. Its vivid and elegant

prose lift it far above the tedious wordiness of visionary and channelled writing.

In sheer weirdness of imagination it rivals the fantasy

fiction of H.P. Lovecraft or Jorge Luis Borges, while in deadpan seriousness and titanic self-

confidence it compares to prophetic works like the Book of Ezekiel or the various

Apocalypses. And it reminds us that the Earth is a very complex place, with many unexplored

corners, many enigmas, and many surprises in store for us surface-dwellers.

yogaesoteric

January 16, 2020