Farewell, Sukhumi – Georgian protesters unwittingly imperil their nation’s survival (2)

Read the first part of the article

In September 1993, when the fate of Sukhumi hung in the balance, it was Mingrelian militias under the control of Loti Kobalia, a Gamsakhurdia loyalist, who blocked the train carrying Georgian reinforcements to Abkhazia, disarming them, and dooming the Sukhumi garrison—and the civilian population they protected—to defeat.

And in October 1993, after the fall of Sukhumi, tens of thousands of Georgian refugees who were fleeing for their lives had to make the journey through the mountains of Zemo Svaneti, where armed gangs of their erstwhile Svan allies set up roadblocks, robbing the desperate Georgians of whatever possessions they had managed to bring with them, before sending them on a journey over the snow-covered Kodori Gorge, where scores of women, children, and the elderly perished of exposure and starvation.

Sukhumi, the capitol of Abkhazia where my wife was born and raised, is no longer under Georgian control. Yes, it was the Abkhaz militias, backed by Russia, the Chechens, Armenians, and other northern Caucasus peoples who carried out the attacks that led to the slaughter of thousands of Georgian civilians and the ethnic cleansing of more than 200,000 others, including my wife, her brother, and their parents.

Yes, it was the policies of Soviet ideologues such as Mikhail Andreyevich Suslov that helped foster and nurture the separatist imaginations of the Abkhaz and other northern Caucasus peoples as a counter to nascent Georgian nationalism.

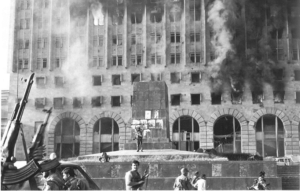

But the origins of the Abkhazian conflict of 1992-93 can be traced to the nationalistic excesses of Georgians as well. It was the criminal gangs of Jaba Ioseliani’s paramilitary Mkhedrioni (“Horsemen”), whom Eduard Shevardnadze unleashed on Sukhumi in August 1992, that transformed what had been a political dispute between Georgia and its Abkhaz minority into a Civil War which Georgia eventually lost.

Georgians betraying Georgians is a theme, it seems, one that cost Georgia its Abkhazian territories, including the city of Sukhumi, in 1993, and which today appears hell-bent on setting up Georgia for its lemming-like effort to provoke Russia into a war that Georgia cannot win, and which, if it occurs, it will not survive as a modern, viable nation state.

Yes, you brave sons and daughters of Georgia—chant your slogans, eat your Khinkali and Khachapouri, drink your Kvanchkara, and watch your women dance the Kartuli, before regaling yourself with the masculine drama of the Khoroumi.

But remember that the Khoroumi is the dance of a defeated people whose ambitions of glory were, always and inevitably, crushed by the power of larger neighbors.

Russia is a larger neighbor.

The youth of Georgia would do well to consider the following: few, if any, Americans can appreciate the role of Khinkali and Khachapouri in Georgian life, or the history of Georgian wine-making that is encapsulated in Kvanchkara, the social intricacies of the Kartuli, and the painful history behind the Khoroumi. To most Americans, it is just food, wine, and some funny dancing.

This is the reality of the society you Georgians are betting your future on—America doesn’t care about you.

Americans don’t even really like you. We barely tolerate your food and wine, and we view your culture as a mere curiosity.

History clearly shows that we are definitely not going to die for you.

You exist only to serve our larger geopolitical goals and objectives.

You are nothing more than part of the “belt of instability” being installed by the United States along Russia’s periphery.

Reflect on that for a moment—Georgia’s American purpose is to generate regional instability. Who pays the price?

Not America.

Georgia.

Georgia is but a smaller version of Ukraine, another cog in the American “belt of instability.”

Reflect on that as you act on the American-driven goal of opening a second front against Russia.

Reflect on the fate of Ukraine.

Reflect on the hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian dead.

Reflect on the tens of millions of displaced and homeless Ukrainian people.

Reflect on the trillion-plus dollars of infrastructure damage to Ukraine.

Reflect on the Ukrainian territory now permanently lost.

Reflect on the fact that Ukraine will, as was the case with Afghanistan before it (and South Vietnam before that), ultimately be abandoned to its fate by its good “friends,” the Americans.

And understand that what Russia has done to Ukraine in a year can be accomplished against Georgia in less than a month.

Georgia will lose Abkhazia and South Ossetia for good, forever. Russia may very well take Poti for good measure, along with Gori and Kutaisi. And why not? If Georgia wants to transform itself into a permanent military threat to Russia, then Russia is obliged to permanently remove that threat.

Once Georgia begins being carved up, Turkey may take Adjaria. This is not idle speculation—Turkish President Recep Erdogan has been making statements about Turkey’s historic claim to Batumi under the terms of Attaturk’s “National Contract,” or Misak-i Milli, of 1920, which set forth the terms of the founding of the post-Ottoman modern Turkish Republic.

Once Georgia begins to be partitioned, there is not a nothing the United States, the European Union, or NATO can or will do about it.

Georgia will cease to exist as a viable modern nation state.

Guaranteed.

Why? Once again, I remind the people of Georgia—America doesn’t like you.

We are not your friend.

We are using you.

And when we are done using you, we will abandon you.

I’ll leave every Georgian reading this to reflect on the following:

Russian women can knead the dough used to make Khinkali with the same patient skill as the women of Georgia, because they have Georgian friends and relatives with whom they grew up doing just that as an act of social bonding.

Russian women can appreciate the intricacies associated with making the different styles of Khachapouri, because they have vacationed in Georgia, and know the pleasant culinary vagaries of its different regions.

Russian men can discard the Khinkali tops with abandon, devouring slices of Khachapouri, because eating Georgian food is second nature to them—they have done so all their life. Georgian cuisine is not foreign to them—it is their cuisine, because every Russian city of note has at least one Georgian restaurant. And they can do this while chasing each savory bite with a sip of Kvanchkara, all the while discussing the legacy of Stalin with a level of detail and passion that only comes from being raised in the shadows of a shared legacy.

Georgians and Russians bled together in the Great Patriotic War.

Georgians and Russians suffered together in the Gulag.

Georgians and Russians studied together in the same universities.

Georgians and Russians have married and raised families together.

Russians watched the Kartuli and Khoroumi being performed just like Georgians watched Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, with a mutual appreciation of the cultural and historical importance and relevance of each step, each gesture, each movement, because it was their shared culture.

In 1829, a Russian poet, Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin, wrote “Upon the Hills of Georgia,” following the rejection of a marriage proposal. He joined the Russian Army, and was sent to serve in Georgia where, in the foothills of the southern Caucasus Mountains, along the banks of the Aragvi River, he penned this classic verse of unfulfilled love:

“Dark falls upon the hills of Georgia,

I hear Aragva’s roar.

I’m sad and light, my grief – transparent,

My sorrow is suffused with you,

With you, with you alone. My melancholy

Remains untouched and undisturbed,

And once again my heart ignites and loves

Because it can’t do otherwise.”

Pushkin knew and understood Georgia. He had read Shota Rustaveli, and from such a foundation he was able to write a poem about unrepentant love, set in the beauty of Georgia, as told by a man whom many have come to recognize as representing the very soul of Russia.

Pushkin’s words served as an inspiration for other Russian writers, such as Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov, another Russian officer who spent time in Georgia, and who became known as “the poet of the Caucasus.”

My point is simply this—Russians know Georgia. Russians understand Georgia.

The fact of the matter is, despite all of the difficulties between Russia and Georgia, Russia is, and forever will be, a better friend to Georgia than America.

The people of Georgia have allowed themselves to be seduced by the illusion of American friendship into believing that the road to Sukhumi runs through Washington, DC and Brussels, when all along all they had to do was keep the road to Moscow open, and Sukhumi could be theirs again.

I watch in sorrow as the misguided youth of Georgia chant the name of a city they have never known and, because of their misguided actions, will never know. And as I listen to their foolish words, I understand that, unless Georgia changes course, my family and I, together with all of Georgia, should bid farewell to the city we know and love, because if Georgia opens a second front against Russia, Sukhumi will be lost to us forever.

Author: Scott Ritter

yogaesoteric

May 18, 2023