Italy 2020: Inside Covid’s ‘Ground Zero’ in Europe (1)

Three years ago the Western world came to a standstill. The official covid-19 narrative depicted a strange suddenly-super-spreading, deadlier-than-flu virus hailing from China that landed in Northern Italy.

On February 20, 2020 the first alleged case of covid-19 was discovered in the West in the Lombardy town of Codogno, Italy. Later that day the Italian government reported their first “covid-19 death.”

Dramatic media reports emerging from Northern Italy were hammered into and onto the Western psyche giving the impression there was a mysterious “super spreading” and “super lethal” novel virus galloping across the region infecting and killing scores of people.

Harrowing reports out of Bergamo, a city in the alpine Lombardy region of Northern Italy, spoke of coffins stacked high, “covid-related deaths growing relentlessly” and the alarming need for military assistance to remove the grim volume of dead bodies piling up.

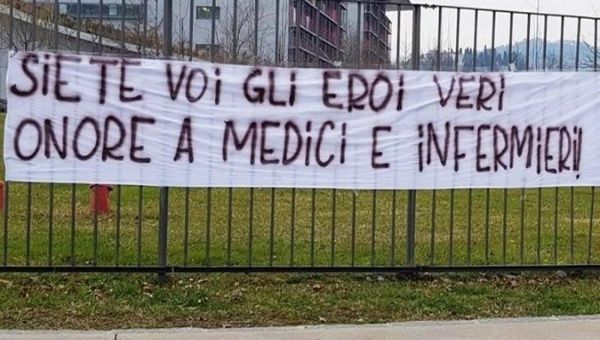

In early March 2020 hospitals in Northern Italy were reporting a “tsunami of deaths” due to the covid crisis and overcrowded conditions due to “fighting the coronavirus outbreak”, which were pushing hospitals and staff to the breaking point as doctors were “taking the dead from morning until night.”

Using the entire machinery of the state, Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte began issuing a rolling set of government decrees culminating in Italy becoming the first country in the world to implement a national lockdown. These mandates would set the stage for lockdowns throughout the Western world.

Three years later a comprehensive evaluation of the story about the alleged Italian medical emergency in spring 2020, reveals a tale of the disturbing epidemiological history of Northern Italy, mass media manipulation and deceptive reporting utilized to create the illusion of a new epidemic.

A multitude of questions and inconsistencies surrounding the Italian story soon surfaced. Ascribing this strange set of convergent circumstances to a viral event strained credulity.

Were these overcrowded conditions in Italian hospitals genuinely the result of a unique viral pathogen or were there other causal factors?

Were these anomalous spikes in excess deaths in Northern Italy verifiably caused by the arrival and spread of a novel deadly virus?

How was it that this virus spread across thousands of kilometers within days and peaked synchronously in selected locations?

How was it that this virus was able to spread so fast across thousands of kilometers, peaking at the same time in those selected locations, yet wasn’t contagious enough to spread to nearby locations?

How was it that this virus waited for a government decree and only then began to create excess death?

How was it possible that all countries in the West and beyond adopted similar “health” measures as carried out in Italy, virtually “overnight”, measures that resembled a de facto police state rather than medical initiatives?

Why Italy?

A brief timeline of the series of events as they unfolded in Northern Italy in spring 2020:

January 31, 2020 – The Italian Council of Ministers declares a 6-month national emergency handing the coordination of the covid-19 emergency responses to the Head the Civil Protection Department, following the detection of the first two covid-19 positive people in Rome – two Chinese tourists traveling from Wuhan;

February 20, 2020 – First covid-19 case of Italian citizen diagnosed in Codogno. 78-year-old Adriano Trevisan, a retired bricklayer from the village of Vo’ Euganeo near Padua in the Veneto region became the first covid death of a European recorded. The deceased tested positive for the virus and died in the hospital while being treated for pneumonia.

February 23, 2020 – The Italian government introduces the first movement and access/exit restrictions around hotspots, known as ‘lockdown red zones.’ On this same day the Italian Ministry of Health issued PCR testing guidance to 31 labs across Italy. Cases surge.

February 25, 2020 – Further restrictive measures introduced across Italy.

February 27, 2020 – A National Surveillance system, coordinated by the ISS (National Institute of Health) is set up to oversee the collection and collation of daily data.

March 1, 2020 – Creation of ‘lockdown red zones’ expands.

March 4, 2020 – Nationwide closure of schools and universities are declared in Italy.

March 8, 2020 – Decree of the President of the Council Of Ministers expands restrictions to all Lombardy and large areas of Northern Italy.

March 9, 2020 – The government of Italy under Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte extends the lockdown to the whole of Italy restricting the movement of the population except for necessity, work, and health circumstances.

March 11, 2020 – The World Health Organization declares the novel coronavirus (covid-19) outbreak a global pandemic. Italy declares closure of all restaurants, pubs, theaters and social activities.

March 18, 2020 – European Central Bank announces huge money printing program to keep the financial system functioning. 750 billion euro bailout given to financial sector to fight the “coronavirus crash.”

March 22, 2020 – Cessation of all non-essential productive activities complete lockdown factories are closed and all nonessential production is halted across Italy.

March 25, 2020 – Further restrictions imposed to people’s movements except for essential reasons (e.g. work, health and getting supplies).

March 27, 2020 – Peak in number of daily covid deaths in Italy.

April 9, 2020 – ‘Liquidità’ Decree goes into full effect, including temporary measures to facilitate access to loans, support business continuity and corporate liquidity and measures to support export, internationalization and business investment.

May 4, 2020 – Reopening of most factories and various wholesale businesses, within pre-set health safety protocols.

While such a chronology can serve to refresh our memory and provide a coherent understanding of the sequence of events, it is not a substitute for real history.

As they say– the devil is in the details.

The details in Northern Italy start with massive pollution problems and the accompanying long-standing chronic health conditions which have afflicted the region for years.

Pollution and Chronic Illness

Everyday life in the Lombardy region is bedeviled with dangerous living conditions and health challenges – numerous acute health problems facing an aging population have been documented for a long period of time.

The Po River Valley in Northern Italy is cited as having the worst air quality in all of Europe. The air quality in the region has been deteriorating for many years. The cities in the Po River Valley are cited as having the highest mortality burdens associated with air pollution in all of Europe.

Along with the sheer volume of pollutants, the Po River Valley is known for its unique characteristics of low winds and prolonged episodes of climatic inversions turning it into a holding tank for atmospheric pollution.

The Lancet Planetary Health report from January 2021 estimated death rates associated with fine particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide pollution in 1,000 European cities. Brescia and Bergamo in the Lombardy region held the morbid distinction of having the highest death rate from fine particulate matter in Europe. Two other Northern Italian cities, Vicenza and Saronno placed fourth and eighth respectively, in the list of top ten cities in this category. These locations correspond precisely with the highest incidents of upper respiratory infections occurring in Northern Italy as reported in the official pandemic narrative.

Ongoing and accelerating “epidemics” of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, (a severe and progressive lung disease), interstitial lung disease and high rates of bronchial and lung cancer were signature epidemiological features of Northern Italy long before an alleged virus ventured onto the scene.

In the Lombardy region there is also an ongoing asbestos problem from occupational asbestos exposure in the 1960s and 1970s. A 2016 study, Incidence of mesothelioma in Lombardy, Italy: exposure to asbestos, time patterns and future projections, predicted a rise of malignant mesothelioma (MM), an aggressive and deadly form of cancer primarily impacting the linings of the chest and abdomen. “This study documented a high burden of MM in both genders in the Lombardy Region, reflecting extensive occupational (mainly in men) and non-occupational (mainly in women) exposure to asbestos in the past. Incidence rates are still increasing; a downturn in occurrence of MM is expected to occur after 2019”, authors said.

A further study, Investigating the impact of influenza on excess mortality in all ages in Italy during recent seasons (2013/14–2016/17 seasons), reveals that rates of death due to the common flu have increased markedly over the past decade. This study described a nearly fourfold increase in flu mortality during the covered time period. By the 2016/17 season the totals skyrocketed to 24,981 excess deaths attributable to flu epidemics.

Adding to the ongoing problems of air pollution, residents in the Po River Valley are plagued by high levels of industrial livestock runoff in rivers and tributaries.

The Lombardy region creates vast amounts of animal waste as it produces more than 40 percent of Italy’s milk production while over half of Italy’s pig production is located in the Po River Valley.

Throughout Italy issues with poisoned soil caused by past and present industrial activities and accidents have beset the land and its people.

Heavy industrial activity and past industrial poisoning in northern Italy afflict the region with yet another mass of toxic exposures.

In 1976 Seveso, Italy experienced “one of the worst industrial accidents in the past century. The Seveso disaster occurred in a chemical manufacturing plant 12 miles north of Milan in the Lombardy region of Italy. It resulted in the highest known exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in residential populations in history and became a testament to the lasting effects of dioxin.”

Dioxin is a known cancer-causing agent and many people who were living in and around Seveso at the time would be at increased risk of cancers later in life. Someone who turned 20 years of age in 1976 would now be in their 60s during the covid era.

This is consistent with what has been widely reported among Nembro men, with cancer being the leading cause of death in this demographic and lung cancer being the most common type of the disease.

Austerity Measures and Health Infrastructure

Compounding the abysmal environmental conditions facing the people of Northern Italy are austerity measures of the past two decades which have decimated Italian public services, severely decreasing health care resources.

Examining the state of the hospitals in northern Italy, long before the “pandemic”, a pattern starts to emerge.

A 2019 review on the current state of Italian hospitals, Health & Hospitals in Italy. 17th Annual Report, noted a “significant increase in 2019 of people on waiting lists and for longer times, compared to the already problematic situation in 2018,” and a, “pronounced deterioration, over the last 5 years, of the connection systems between general medicine and hospitals and between these and post-hospitalization services (rehabilitation, long-term care, assisted living homes and home care service).”

The charged atmosphere and resulting firestorm created by a trumpeted “viral invasion” brutally exposed the effects of 20 years of cuts to the national health care system.

A 2013 Oxfam report on the impacts of austerity measures, The True Cost of Austerity and Inequality Italy Case Study highlighted the decline in Italian health services.

The report noted that in 2000, Italy was 2nd in the world for health coverage. The reports cited that by 2011, due to yearly declines in health spending, “more than nine million people declared that they could not access some health services for economic reasons.”

Further cuts magnified an already volatile situation. Over the period 2010–19, the Italian National Healthcare Service suffered financial cuts of more than €37 billion as it experienced a progressive privatization of health-care services. Government spending on healthcare, decreasing for years, spiraled down to a rate below what the W.H.O. considered capable of offering basic health care.

These comprehensive cuts also had severe effects on the healthcare workforce and available hospital beds and equipment, effectively hampering the ability of care facilities to effectively treat patients.

The period from 2009 to 2017 saw 5.2 percent of healthcare staff cut. In the last 10 years, 70,000 beds were lost. In acute medical units bed availability dropped from 922 per 100,000 inhabitants in 1980 to 262 per 100,000.

Data from 2020 show a total of 5,179 beds in intensive care units (approx. 8.9 beds per 100,000) for all of Italy, a population of just over 60 million in 2020.

At regular operational level in 2020 the 74 Lombardy hospitals, servicing a population of 10 million, had approximately 720 ICU beds, with up to 90% of them usually occupied in the winter.

By March 10, 2020 there were 877 people hospitalized in ICUs, units in Lombardy were saturated and requests to transfer patients to other regions were prevalent.

The net effect of these radical cuts to hospital infrastructure and services in the context of the covid hysteria were predictable: for years Italian ICU physicians have been reporting that flu outbreaks cause ICU units to fill up as was the case in locations across the world.

The roaring silence from the media on these inconvenient facts kept the public in the dark on the realities of the crumbling Italian health care system.

In light of this data, it is no surprise that people with routine and mostly reversible seasonal respiratory infections once admitted to hospitals might not be treated appropriately or successfully.

In spring 2020 Italian health officials introduced unprecedented health protocols specifically for covid.

These new protocols, including early intubation and accompanying sedation, were deemed necessary to protect doctors and nurses at a time when the viral load of the alleged lethal pathogen was purportedly lower.

Were these new protocols appropriate for treating upper respiratory problems?

Mechanical ventilators, that push oxygen into patients whose lungs are failing, quickly became the accepted go-to practice throughout the Italian hospital system. Doctors made extravagant claims that ventilators had “become like gold.”

Employing ventilators involves sedating the patient and placing a tube into the throat. Drugs such as midazolam, morphine sulfate and propofol are used in accompaniment with this procedure; drugs that come with contra-indications and warnings of side effects including respiratory depression and respiratory arrest. Midazolam and propofol are two drugs that are regularly used for assisted suicide and to put down death row inmates.

During the initial wave of hysteria in March 2020 the Italian government requested and received an emergency procurement of midazolam from Germany as their hospitals “suddenly needed 3-4 times the normal amount of this drug.”

The Italian Civil Protection undertook a fast-track public procurement to secure 3,800 additional respiratory ventilators.

As early as April 2020 the reliance on mechanical ventilation came under fire from Italian experts. Luciano Gattinoni, a world-renowned Italian intensive care specialist suggested that “mechanical ventilation was being misused and overused.”

Marco Garrone, an emergency doctor at the Mauriziano Hospital in Turin, Italy remarked, “We started with a one-size-fits-all attitude, which didn’t pay off,” Garrone said of the practice of putting patients on ventilators right away, only to see their conditions deteriorate. “Now we try to delay intubation as much as possible.”

Even as some health officials pushed to get more ventilators to treat coronavirus patients, some doctors were moving away from using them.

Questions surrounding actual causes of “covid deaths” of the frail and elderly placed on ventilators began to surface for the simple reason that doctors were noticing unusually high death rates for coronavirus patients on ventilators.

Could it be that it was medical malfeasance, and not a novel pathogen, that was igniting this tinderbox in the hospitals and creating a feedback loop of public panic?

Could it be that what spread through the Italian hospitals in Spring 2020 was an epidemic of iatrogenesis?

Was it possible that the spring 2020 mortality event in Northern Italy was not an epidemiological or biological aberration but the result of an unprecedented set of administrative mandates by the Italian government and public health officials?

Emergency Measures and Lockdown Impacts on Population

The Italian government, public health officials and regional doctors proclaiming a “novel virus” had landed in Northern Italy, insisted that emergency preparations be activated to prepare for this “massive” increase in covid-19 patients. That these forecasts were speculations, using linear model forecasts, coming from doctors with conflicts of interest was of little interest to reporters.

A progressive set of restrictive decrees, including lockdowns of villages and cities, were swiftly implemented. These directives served to further terrify and disorient an already panicked populace.

Citizens were told to stay home and were banned from entering certain areas; fines were levied for those who transgressed. Most shops and businesses were ordered to shut down.

Residents described the abandoned streets as surreal and “fearful.”

Farm owner Rosanna Ferrari said, “We’re experiencing a bit of a panic. Supermarkets have been stormed. There are queues outside of the chemist. They said they’ll come, house to house, to collect saliva samples today.”

Angelo Caperdoni, the mayor of Somaglia, described the alarming situation, “It was difficult to contain the panic at first, especially as a lot of false news was circulating on social media that people believed to be true. There is still panic regarding food provisions. Many people went to Codogno to try and stock up.”

Franco Stefanoni, the mayor of Fombio, also under lockdown, described the harried scene in military terms as he noted the town’s two mini-markets had been “besieged”, as “people have been racing to the supermarket to buy 20kg of pasta or 30kg of bread.”

Former president of Italy’s higher health council, Roberta Siliquini, provided a more reasonable explanation for the excitement: “We have found positive cases in people who probably had few or no symptoms and who may have overcome the virus without even knowing it.”

Cooler heads advising calm were systematically buried beneath a barrage of draconian government edicts, manufactured hype from vested interests and the sustained onslaught of media agitation and deceptive reporting.

Read the second part of the article

yogaesoteric

April 21, 2023

Also available in:

Română

Română