JNANESHVAR: A star in the spiritual sky

Jnaneshvar or Jnandev was born in 1275 AD in a small town in Western India (Maharashtra), called Alandi. During that time, the Maharashtra region was an independent state (which had not yet suffered from the invasion of Muslim hordes coming from the north) and was led by King Ramadevarao, from the Yadav family.

Jnaneshvar or Jnandev was born in 1275 AD in a small town in Western India (Maharashtra), called Alandi. During that time, the Maharashtra region was an independent state (which had not yet suffered from the invasion of Muslim hordes coming from the north) and was led by King Ramadevarao, from the Yadav family.

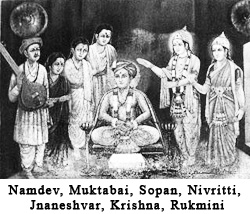

Jnaneshvar and his two brothers, Nivrittinath (his spiritual Guide) and Spoan, with his sister, Muktabai, were the children of a sannyasin who, forced by circumstances, had to adopt a family life. This was the first event in the history of the Maharashtra state in which a man returns to family life after making the religious covenant and wearing the orange robe. And this unfortunate event caused suffering not only to the parents but also to their children. In those days the Orthodox influence and power were so great that the family was ostracized by the entire population of Alandi, being forced to live in a hut outside the city. The mere sight of a family member was considered an ominous sign!

Jnaneshvar’s father, Vitthalpant, had inherited a small job as a government official in Pegaon, a village near Paithan, a great spiritual centre. Apparently Vitthalpant was strongly affected by his father’s death and decided to give up worldly life. His father-in-law, who had held a responsible position in the City Hall of Alandi, invited Vitthalpant and his wife Rakhumabai to live with him in Alandi. For several years, the couple didn’t have children and this contributed to the widening of Vitthalpant’s contempt for the world, while his previous desire to become a sannyasin had become stronger and stronger. His wife, seeing her husband’s internal torments, reluctantly gave her consent so that he would get initiated and give up family life. Having his wife’s agreement, he immediately went to Benares, where he was initiated in the order of the sannyasins by the great ascetic Swami Ramanand, who gave him the name Chaitanyashrama. When his wife heard the news that her husband had become a sannyasin, she considered that this meant the end of their marriage, and adopting the lifestyle of a widow, spent all the time praying near the sacred ashvatta tree at the temple of Alandi, which was why she was respected and regarded by all as a very pious woman.

Twelve years later, during a pilgrimage, Vitthalpant’s spiritual guide arrived in Alandi. One day, while he was sitting in the courtyard of the temple saying his prayers and counting his rosary beads, Rakhumabai saw Swami Ramanand, and as she used to, she bowed before him with great reverence and then slowly stepped aside. Swami Ramanand, impressed by the spiritual brilliance on the woman’s face, blessed her with the traditional: “May God give you many children.” Rakhumabai could not resist and smiled melancholically. The spiritual Guide, a little intrigued by that sad smile on the face of such a pious person, started a conversation with her and, finally, heard the woman’s whole story, including the fact that her husband was no other than his disciple, Chaitanyashrama. Then Swami Ramanand understood clearly that although Vitthalpant had obtained his wife’s agreement, she had not given it with all her heart, but was forced to give in to his request based on a stratagem. The spiritual Guide promised the woman that he would return immediately to Benares and will do everything possible to persuade Vitthalpant to return to her.

Thus, when Swami Ramanand was back in Benares, he ordered Vitthalpant to go to Alandi and fulfill the obligations of a husband and told him that he could return to Benares only after he and his wife would conceive and carry out the duties of parents. Soon, Rakhumabai gave birth, at short intervals, to four children.

Thus, when Swami Ramanand was back in Benares, he ordered Vitthalpant to go to Alandi and fulfill the obligations of a husband and told him that he could return to Benares only after he and his wife would conceive and carry out the duties of parents. Soon, Rakhumabai gave birth, at short intervals, to four children.

Vitthalpant’s return to family life caused a real shock among the Orthodox brahminis in Alandi and his action was regarded as a defiance against the sannyas’s sacred institutions which, as the Hindu scriptures say, is the last stage on the path to human perfection. For this reason the whole family was morally condemned and excluded from society – an attitude that caused much mental suffering, both to parents and children, who were always described and named “the sannyasin’s children,” never by their name.

After Nivrittinath, the eldest son, turned six, his family faced the first major problem: according to tradition, in any brahmin couple, the boys must pass, in the eighth year of life through the ritual ceremony of initiation into religious life – without it they cannot become brahmins. Disturbed, the father went and begged on his knees on the Alandi brahmin-s to fulfill his eldest son’s initiation ceremony, but they did not even want to hear about it.

Consequently, faced with this reluctant attitude, Vitthalpant moved his family to Nasik, in the hope that there he will be able to redeem his mistakes by the severe penances to surround the Brahmagiri hill, from which the sacred river Godavari springs. Incessantly for six months, they surrounded the hill every day, after first having washed daily in the river at midnight. Meanwhile, fate was following its predestined course and one night a tiger came to them from a bush and roared horrifically, forcing them to flee to survive. The father managed to keep the three younger children to his side. But the eldest boy, Nivrittinath, got lost and finally got to a cave where he was waited for by his spiritual guide, Sant Gaininath, incarnated as a spiritual tiger. Sant Gaininath accepted Nivrittinath as a disciple and initiated him into spirituality. A few days later, Nivrittinath returned home as a fully enlightened spiritual aspirant of the magnificent Gaininath. And Nivrittinath was the one who later gave the initiation and the spiritual guidance to Jnaneshvar, Sopan and Muktabai. The parents were happy and excited about the unexpected way in which things happened and felt that their life goal had been fulfilled.

Life still had to go on and Nivrittinath, despite his spiritual realization, was forced by tradition to go through the ritual of initiation into spirituality. Therefore, Jnaneshvar’s father went back to the priests of Alandi and asked them to tell him what other penances he had to go through to remove the sin done by his wife and himself, swearing that he would submit to their word, regardless of how difficult the task given would be. The brahminis studied the scriptures and finally they gave the verdict, saying that only death could wash such an unprecedented sin. The parents prayed for their children’s welfare and after midnight they crept out of the house and went to the holy city of Prayang, where they abandoned their bodies to mother Ganga.

The deliberate sacrifice of the parents, still did not resolve the children‘s problem. When they returned to the priests of Alandi, who, although they had begun to like them, said they had no authority to forgive and they suggested them to go to Paithan and get a certificate of purification from the Supreme Council of the Brahmin-s. Paithan is about 300 km far from Alandi and after a very difficult journey the children got to town 17 days later. Fortunately for them, the Council was in session and the most educated and wise brahmins in the region were present there. The children’s problem was immediately subjected to debate, and hence the same difficulty also showed up here, the pundits told the children that they had no authority in this respect and that all they could do was to interpret what was written in the scriptures regarding a situation like this. Strange are the ways of Providence.

The deliberate sacrifice of the parents, still did not resolve the children‘s problem. When they returned to the priests of Alandi, who, although they had begun to like them, said they had no authority to forgive and they suggested them to go to Paithan and get a certificate of purification from the Supreme Council of the Brahmin-s. Paithan is about 300 km far from Alandi and after a very difficult journey the children got to town 17 days later. Fortunately for them, the Council was in session and the most educated and wise brahmins in the region were present there. The children’s problem was immediately subjected to debate, and hence the same difficulty also showed up here, the pundits told the children that they had no authority in this respect and that all they could do was to interpret what was written in the scriptures regarding a situation like this. Strange are the ways of Providence.

While the council members were parting, a more mischievous brahmin could not refrain and being in the position to annoy the poor children a bit, asked the eldest of them what his name was. After receiving the response, the brahmin added quizzically that probably he didn’t even know what that name meant. Nivrittinath replied: “I am Nivritti, inside and yet outside the world.”

Jnaneshvar replied: “I am Jnandev, the embodiment of the Divine and Absolute knowledge.”

And Sopan who was only six years old, said: “I am Sopan and I own the scale that can lead to paradise.”

The brahmin, feeling hurt, turned to Muktabai and pinching her cheeks quite hard, asked: “And this pipsqueak can she speak?” Without the slightest trace of anger, Muktabai fully serious, replied in a crystalline voice, “I am issuing the eternal mother who liberates not sinners, but souls.”

Meanwhile, the other wise men listened pleasantly impressed by the children’s answers and giggled at the mess their colleague got himself into. Enraged, the brahmin turns to Jnaneshvar and says: “But what is a name? Look, even this ox which carries water from the river daily, is called Jnanya, but he can not recite the Vedas.” Jnaneshvar replied calmly: “The same consciousness that exists in my body, there is also in the body of the ox.”

When the brahmin heard Jnaneshvar’s words, his rage surpassed everything. Then the brahmin grabbed the whip from the hand of the disciple running the ox and was ready to unleash his nerves on the young Jnaneshvar, but due to the crowd who was watching the whole scene, he refrained from doing that and instead began to whip the poor animal with anger. In that moment the first miracle happened, witnessed by a few hundred people who had gathered there. With each stroke applied to the back of the ox, the traces of those strokes appeared on the back of young Jnaneshvar, but Jnaneshvar was accepting them stoically. When the brahmin stopped ashamed of his action, Jnaneshvar tenderly stroked the ox and said: “Jnanya, my brother, now it is your turn to prove to these people that the source of your existence and of my existence is identical and that, despite the distinction between our forms, in reality we are not different. Therefore, please recite for me the Peace Song from the holy Rig Veda.” And, miracle! The animal bowed his head in sign of reverence towards Jnaneshvar, looked towards the Sun of Heaven and sang the song while maintaining a perfect pace and harmony.

A deep silence was laid over the crowd and in that silence one by one people fell on their knees and bowed respectfully to the young Jnaneshvar. Then, the head of the brahmins came and said humbly: “It may be that you are the children of a simple sannyasin, but it is obvious that you are the incarnations of the BRAHMA-VISHNU-MAHESHVAR triad and your sister is no other than ADIMATA, the eternal Mother herself. How can we dare give you a certificate of purification? All we can do is to grovel before you and apologize.”

A deep silence was laid over the crowd and in that silence one by one people fell on their knees and bowed respectfully to the young Jnaneshvar. Then, the head of the brahmins came and said humbly: “It may be that you are the children of a simple sannyasin, but it is obvious that you are the incarnations of the BRAHMA-VISHNU-MAHESHVAR triad and your sister is no other than ADIMATA, the eternal Mother herself. How can we dare give you a certificate of purification? All we can do is to grovel before you and apologize.”

In the next period, thousands of people came on pilgrimage in Paithan to see flashing of the Divine manifested in Jnaneshvar’s brothers and sister and to listen to the sermons which he would give daily. After a few weeks in Paithan, the little family of saints returned to Alandi and presented the brahmins the cerificate attesting their purification. But their fame had got to the city long before them and the entire population, which hitherto disregarded them calling them “the sannyasin’s children” came to welcome them with flowers and garlands, but with hearts full of remorse and eyes bathed in tears.

(Extract from Amritanubhava commented by Ramesh Balsekar)

Works of Sri Jnaneshvar

In Nevase, at the age of 15, Jnanadeva wrote magnum opus Jnaneshvari. This work, which is a commentary on Srimad Bhavagad Gita was written in a dialect of marathi, for the benefit of ordinary people who had no opportunity to study the Vedic literature. Srimad Bhavagad Gita exhibits the teachings of Bhagavan Sri Khrishna in about 9,000 ovis, a form of prosody of two and a half lines, usually sung by women from the villages of Maharashtra during the turning of the cereals (on the other side to dry).

Tradition says that after he finished Srimad Bhavagad Gita, Jnaneshvar showed it to his brother, whom he considered his spiritual guide. Nivrittinath, although he appreciated his work, said that it was just a comment on another writing and not an independent one.

Inspired by his brother’s words, Jnaneshvar wrote Amritanubhava, known as the Anubhavamrita, in which he described his experience in yoga and philosophy through which one can achieve the experience of the divine nectar, amrita. The subject of this book is abstract and it is approached in a concise and very direct way. Besides these two books, Sri Jnaneshvara also wrote almost 1200 abhangas, but only two or three hundred of them were accepted by scholars as Jnaneshvar’s compositions, the others not conforming to his writing style and expression of ideas.

Mahasamadhi

After writing Amritanubhava, Jnaneshvar went on a pilgrimage to the holy places, together with Namadeva and other saints who lived in those times. After completing the pilgrimage, Jnaneshvar felt that his life mission was completed and expressed his intention to enter the state of samadhi while he was in life (Jivasamadhi). When those present heard about it, they were saddened that this ocean of knowledge that was Jnaneshvar was going to leave. Despite all these, Jnaneshvara was firm in his decision and entered Mahajivasamadhi while he was in Alandi in the presence of his two brothers Nivrittinath and Sopan, and his sister Muktabai. He was then 21 years old.

After writing Amritanubhava, Jnaneshvar went on a pilgrimage to the holy places, together with Namadeva and other saints who lived in those times. After completing the pilgrimage, Jnaneshvar felt that his life mission was completed and expressed his intention to enter the state of samadhi while he was in life (Jivasamadhi). When those present heard about it, they were saddened that this ocean of knowledge that was Jnaneshvar was going to leave. Despite all these, Jnaneshvara was firm in his decision and entered Mahajivasamadhi while he was in Alandi in the presence of his two brothers Nivrittinath and Sopan, and his sister Muktabai. He was then 21 years old.

Once Jnaneshvar entered Mahasamdhi, Nivrittinath, Sopan and Muktabai decided to end their existence in this world and one year after their brother entered Mahasamadhi, they left their earthly existence and in their turn entered Mahasamadhi.

yogaesoteric

September 2011

Also available in:

Română

Română