Orienting Egyptian Pyramids (2)

All nine of the famous pyramids at Giza are closely aligned to true North, and the debate on how this was achieved rages on.

Read the first part of the article

Aligning

Bronze statue of Imhotep, chief architect to the Third Dynasty King Djoser

Egyptian architects, surveyors and builders are known to have used two specialised surveying tools, the merkhet (the ‘instrument of knowing’, similar to an astrolabe) and the bay (a sighting tool probably made from the central rib of a palm leaf). These allowed construction workers to lay out straight lines and right-angles, and also to orient the sides and corners of structures, in accordance with astronomical alignments.

It is clear that the Egyptians were using their knowledge of the stars to assist them in their architectural projects from the beginning of the pharaonic period (c.3100-332 BC), since the ceremony of pedj shes (‘stretching the cord’), reliant on astronomical knowledge, is first attested on a granite block of the reign of the Second-Dynasty king Khasekhemwy (c.2650 BC).

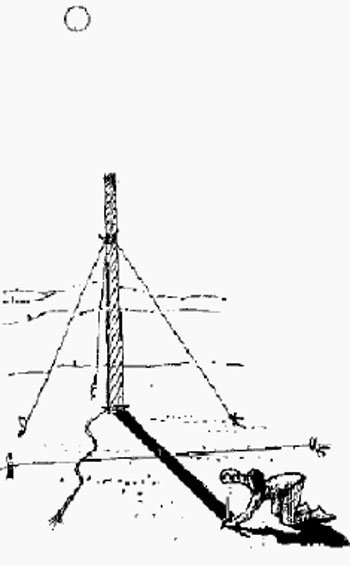

Reconstruction of an official ceremony in which the pyramid is aligned to the stars

This pedj shes ceremony relied on sightings of the Great Bear and Orion constellations, aligning the foundations of the pyramids and sun temples very precisely with the north, south, east and west. They usually achieved this with an error of less than half a degree. In later periods, the process of stretching the cord continued to be depicted in texts and in the reliefs of temples such as that of Horus, at Edfu, but it appears to have gradually become just a ritual, since these temples were aligned less precisely than the earlier ones, often simply with reference to the direction of the river.

How did this astronomically based surveying work in practice? The British Egyptologist IES Edwards argued that true north was probably found by measuring the place where a particular star rose and fell in the west and east, then bisecting the angle between these two points. More recently, however, Kate Spence, an Egyptologist at the University of Cambridge, has put forward a convincing theory that the architects of the Great Pyramid sighted on two stars (b-Ursae Minoris and z-Ursae Majoris), rotating around the position of the north pole, which would have been in perfect alignment in around 2467 BC, the precise date when Khufu’s pyramid is thought to have been constructed. This hypothesis is bolstered by the fact that inaccuracies in the orientations of earlier and later pyramids can be closely correlated with the degree to which the alignment of the two aforementioned stars deviates from true north.

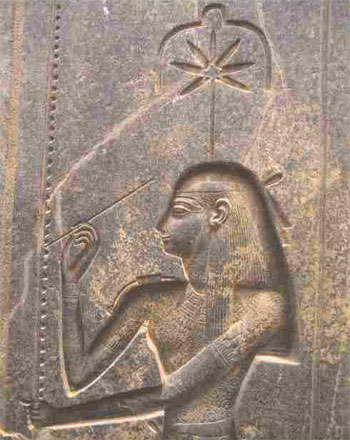

Stretching the cord ceremony – Goddess Seshat

“It appears that there was drawn a plan of the Great Pyramid which included the calculation of the stars to be observed in order to obtain the direction of the north. After this plan was drawn, the ground of the Pyramid had to be cleared in order to proceed to the ceremony called ‘stretching the cord,’ which for the Egyptians was the equivalent of our laying of the first stone. This ceremony had the purpose of establishing the direction of true north and, as the Egyptians saw it, suspending the building from the sky by tying the building with an imaginary string to the axis of rotation of the vault of heaven.” (Tompkins, Secrets of the Great Pyramid, pp. 380 and 381).

Egyptian architects, surveyors and builders are known to have used two specialised surveying tools, the merkhet (the ‘instrument of knowing’, similar to an astrolabe) and the bay (a sighting tool probably made from the central rib of a palm leaf). These allowed construction workers to lay out straight lines and right-angles, and also to orient the sides and corners of structures, in accordance with astronomical alignments.

It is clear that the Egyptians were using their knowledge of the stars to assist them in their architectural projects from the beginning of the pharaonic period (c.3100-332 BC), since the ceremony of pedj shes (‘stretching the cord’), reliant on astronomical knowledge, is first attested on a granite block of the reign of the Second-Dynasty king Khasekhemwy (c.2650 BC).

How was north determined?

Tompkins writes (p. 380): “If my interpretation of Egyptian sky charts is correct, the line that indicates the north used to be marked so as to pass through the celestial pole AND through the pole of the ecliptic.”

In fact the west face of the Great Pyramid “is not oriented to the north, but is oriented 2’30 west of true north.” This deviation from orientation to the north is, according to Tompkins, the result of the precession of the equinoxes from the date of the first plan to the actual laying of the first stone – since precession of the equinoxes “displaces the star taken as the polar star in practical calculations to the west at a rate of about 50” a year.

It is this rate of precession which the Great Pyramid was intended to calculate exactly.

As Tompkins writes at page 382 in concluding his book:

“I have collected a mass of numerical evidence which shows that the inhabitants of the ancient world were acquainted with the rate of the precession of the equinoxes [and solstices] and attached a major significance to it.”

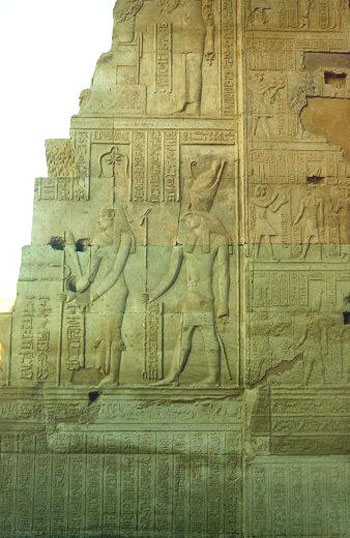

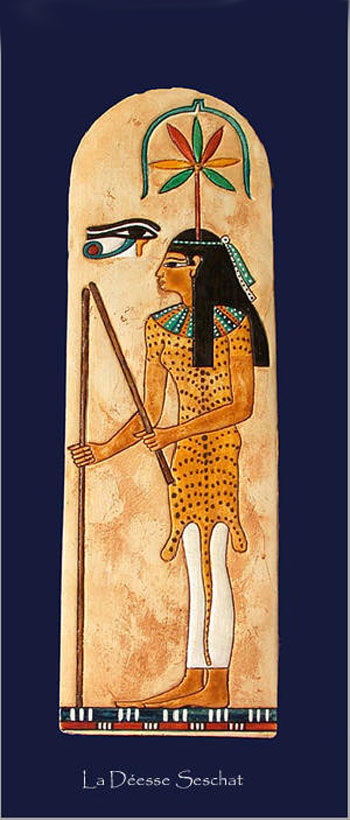

Inside the temple of Kom Ombo we find a pharaoh and the goddess Seshat preforming what is called “stretching the cord”. This act represents the measure and layout of this temple. Seshat, who was the sister and wife of Thoth was the patroness of arithmetic, architecture and records. After preforming this act she would write the kings name on the tree of life, this would assure the kings immortality.

The temple lies in the Egyptian town of Kom Ombo, 45 km north of Assuan, and was built in the Ptolemaic period between the second and first centuries B.C. The temple actually consists of two temples, one dedicated to the Egyptian falcon headed god Horus, the solar war god, and the other one to the Egyptian crocodile god Sobek, who controlled the waters.

Not much of the temple is left nowadays, due first to the changing Nile, then the Copts who once used it as a church, and finally by builders who used the stones for new buildings.

The Pharoah and the Goddess Seshat, planting stakes linked by a looped rope, participate in the ‘Stretching the Cord’ ceremony

Photograph from Werner Forman and Steven Quirke: “Hieroglyphs & the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt”, University of Oklahoma Press, 1996, page 11.

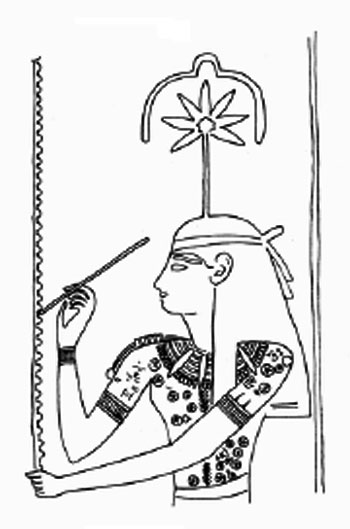

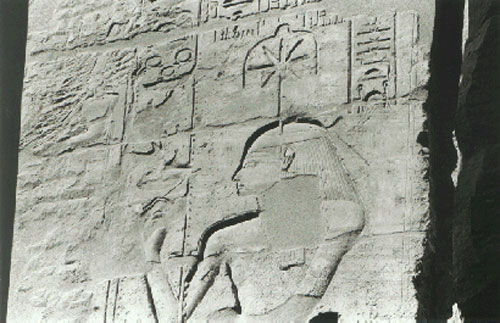

This relief in the Amun temple at Luxor dates from around 1250 BCE and shows Seshat, the goddess of temple geometry and scribal arts, inscribing regnal years for the king on the palm-leaf rib which had long served for tallying up the years and so had become the hieroglyph for “year”.

The emblem in Seshat’s head-dress identified the major tools of her temple layout trade, as explained in the caption to the enlarged view of this telltale detail.

This picture of Seshat’s emblem on a temple wall in Luxor dates from around 1250 BCE. It shows the seven-part leaf of the hemp plant used to make Seshat’s surveying rope.

Detail of Seshat’s emblem on a Luxor temple wall, enlarged from a photograph by Werner Forman in Werner Forman and Steven Quirke: “Hieroglyphs & the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt”, University of Oklahoma Press, 1996, page 11.

That leaf is here framed by a large numeral “ten” with a smaller version of that same numeral on top. This juxtaposition of “tens” clearly described her mastery of numbers from large to small, and her duty to convert the large numbers of the cosmos into the smaller ones used to lay out its reduced replica, the temple.

The five-pointed star at the center of the hemp leaf is a pentagram, slightly distorted to accommodate the stem. The pentagram requires analytical geometry for its construction. Its design was used some 750 years later by Pythagoras as a symbol for his secret mathematical teachings which he had picked up mostly in Egypt.

It appears that the Luxor sculptor used this geometric figure here already with a similar meaning. The context of Seshat’s role makes it a symbol for the advanced mathematics at the core of Seshat’s temple geometry which Pythagoras would later come to study.

How the ancient Egyptians aligned their pyramids?

There are many remaining mysteries as to how the ancient Egyptians constructed their royal pyramid tombs. For example: how did they get all those tons and tons of large stone blocks up the sides? Two things we know for sure: the methods had to be simple and low-tech, and that they had plenty of time to think up their clever ideas.

Before we start considering a possible method they might have used to orient their pyramids so precisely to the compass directions, let’s try to gain some inspiration from the discovery of how they made the foundation surfaces for the pyramids so precisely flat and level. Remember we are not talking about a small area as the base of the largest pyramid covered nearly 13 acres (about 750 feet on a side). Go outside and see just how much that is – several city blocks, if you live in a city. No, this was not a small “building” even by today’s standards!

What the Egyptians did was clear away the sand down to the bedrock, and then they hacked away at the rock to make a level, flat surface. But how did they know that they had made a “level” surface? Simple and low-tech, of course! It was discovered that there is a shallow groove completely around the bases of all the pyramids. When these grooves were cleaned out of all the wind-blown sand, and water was dumped in, the water level was “level” all the way around the pyramid. Thus the flat surface of the foundation was carved away until every portion of it was exactly the same distance above the water level. Simple! Low-tech! Neat, hey?

So now let’s think about how they so precisely oriented each of their pyramids so that one side faced exactly east, another exactly south, and so on. And remember that the magnetic compass wasn’t invented yet for another several thousand years (it wouldn’t have helped them much since magnetic compasses usually don’t point exactly north-south), and they didn’t have any global positioning satellites (they’d have to wait for an additional thousand years!).

You might want to suggest that they used Polaris, the North Star. But the precession of earth’s axis would have meant that Polaris was not close to north at that time. Besides, even if it were, Egypt is so close to the equator that Polaris would have been lost in the haze at the horizon.

What these ancient people did have was a rather thorough understanding of the sun. Afterall, the sun was their chief god, and ancient priests and other scholars studied with great care the sun and its daily voyages across the sky. But how can the sun tell us the compass directions?

In the following, you will not have to wear ancient Egyptian clothing as in the picture, nor will you have to use an ankh staff or use rocks on the desert floor. The obelisk began to lose importance as the end of the Egyptian Empire approached.

Read the third part of the article

yogaesoteric

April 2, 2019