Fractal patterns in nature and art are aesthetically pleasing and stress-reducing

Humans are visual creatures. Objects we call “beautiful” or “aesthetic” are a crucial part of our humanity. Even the oldest known examples of rock and cave art served aesthetic rather than utilitarian roles. Although aesthetics is often regarded as an ill-defined vague quality, research groups are using sophisticated techniques to quantify it – and its impact on the observer.

They’re finding that aesthetic images can induce staggering changes to the body, including radical reductions in the observer’s stress levels. Job stress alone is estimated to cost American businesses many billions of dollars annually, so studying aesthetics holds a huge potential benefit to society.

Researchers are untangling just what makes particular works of art or natural scenes visually appealing and stress-relieving – and one crucial factor is the presence of the repetitive patterns called fractals.

Are fractals the key to why Pollock’s work captivates?

Pleasing patterns, in art and in nature

When it comes to aesthetics, who better to study than famous artists? They are, after all, the visual experts. One research group took this approach with Jackson Pollock, who rose to the peak of modern art in the late 1940s by pouring paint directly from a can onto horizontal canvases laid across his studio floor. Although battles raged among Pollock scholars regarding the meaning of his splattered patterns, many agreed they had an organic, natural feel to them.

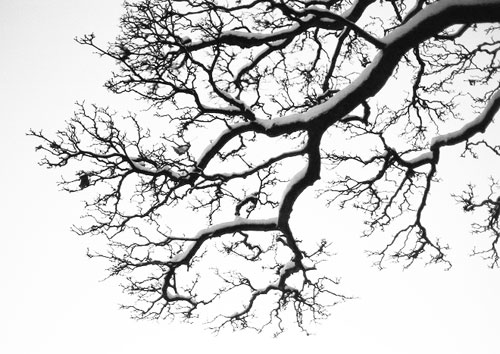

Researchers’ scientific curiosity was stirred when they learned that many of nature’s objects are fractal, featuring patterns that repeat at increasingly fine magnifications. For example, think of a tree. First you see the big branches growing out of the trunk. Then you see smaller versions growing out of each big branch. As you keep zooming in, finer and finer branches appear, all the way down to the smallest twigs. Other examples of nature’s fractals include clouds, rivers, coastlines and mountains.

In 1999, a research group used computer pattern analysis techniques to show that Pollock’s paintings are as fractal as patterns found in natural scenery. Since then, more than 10 different groups have performed various forms of fractal analysis on his paintings. Pollock’s ability to express nature’s fractal aesthetics helps explain the enduring popularity of his work.

The impact of nature’s aesthetics is surprisingly powerful. In the 1980s, architects found that patients recovered more quickly from surgery when given hospital rooms with windows looking out on nature. Other studies since then have demonstrated that just looking at pictures of natural scenes can change the way a person’s autonomic nervous system responds to stress.

Are fractals the secret to some soothing natural scenes?

This raises the same question: Are fractals responsible? Collaborating with psychologists and neuroscientists, a research group measured people’s responses to fractals found in nature (using photos of natural scenes), art (Pollock’s paintings) and mathematics (computer generated images) and discovered a universal effect labelled “fractal fluency”.

Through exposure to nature’s fractal scenery, people’s visual systems have adapted to efficiently process fractals with ease. The researchers found that this adaptation occurs at many stages of the visual system, from the way our eyes move to which regions of the brain get activated. This fluency puts us in a comfort zone and so we enjoy looking at fractals. Crucially, EEG was used to record the brain’s electrical activity and skin conductance techniques to show that this aesthetic experience is accompanied by stress reduction of 60 per cent – a surprisingly large effect for a nonmedical treatment. This physiological change even accelerates post-surgical recovery rates.

Artists intuit the appeal of fractals

It’s therefore not surprising to learn that, as visual experts, artists have been embedding fractal patterns in their works through the centuries and across many cultures. Fractals can be found, for example, in Roman, Egyptian, Aztec, Incan and Mayan works. Some favourite examples of fractal art from more recent times include da Vinci’s Turbulence (1500), Hokusai’s Great Wave (1830), and M.C. Escher’s Circle Series (1950s).

Although prevalent in art, the fractal repetition of patterns represents an artistic challenge. How artists create their fractals fuels the nature-versus-nurture debate in art: To what extent is aesthetics determined by automatic unconscious mechanisms inherent in the artist’s biology, as opposed to their intellectual and cultural concerns? In Pollock’s case, his fractal aesthetics resulted from an intriguing mixture of both. His fractal patterns originated from his body motions (specifically an automatic process related to balance known to be fractal). But he spent 10 years consciously refining his pouring technique to increase the visual complexity of these fractal patterns.

Recognizing how looking at fractals reduces stress means it’s possible to create retinal implants that mimic the mechanism.

Another research focuses on developing retinal implants to restore vision to victims of retinal diseases. At first glance, this goal seems a long way from Pollock’s art. Yet, it was his work that gave a clue to fractal fluency and the role nature’s fractals can play in keeping people’s stress levels in check. To make sure the bio-inspired implants induce the same stress reduction when looking at nature’s fractals as normal eyes do, they closely mimic the retina’s design.

When they started the Pollock study, researchers never imagined it would inform artificial eye designs. This, though, is the power of interdisciplinary endeavours – thinking “out of the box” leads to unexpected but potentially revolutionary ideas.

yogaesoteric

November 4, 2017