American History of the Rothschilds and the Eight Most Powerful Families (2)

Read the first part of the article

The Rothschilds in America

As the years went on, the Rothschilds became more daring. In 1785 they had plans in the works to start the French Revolution, but when those plans were discovered by the authorities, the Illuminati were kicked out of Bavaria.

The country went so far as to send warnings to all the major European states about the Illuminati, but they were ignored, and Rothschild was now safe in Frankfurt.

Their plans for the French Revolution went forward after all, and that allowed them to stop the Catholic Church from issuing taxes as well as create favorable new banking laws through the new nation’s constitution.

By 1791, Rothschild was extending his reach to America, where he convinced Alexander Hamilton to set up the First Bank of the United States with a 20-year charter.

In 1812, Mayer Rothschild died, but his family was large enough to continue – he had five sons and five daughters and an immeasurable quantity of wealth, enough so that he could hold Prince William IX of Hesse-Hanau’s $3 million personal fortune in safekeeping.

More Rothschilds would come and go, but their economic power and vision of a new world order under Satan remained. When the First Bank of the United State’s charter was up in 1811, Congress refused to renew it. This angered the Rothschilds, who called for America to be brought back to “colonial status.” Using loaned Rothschild money, England declared war on the United States, starting the War of 1812.

The idea was to bankrupt the young nation, which had little money and was looking at costs of $10 million for just 1812 alone, mainly because 10,000 men suddenly had to be raised to fight the invading British armies funded by a group of secretive, debt-hungry bankers.

Congress was able to provide the funding through increased customs duties but in 1813 revenues were only going to be $17 million for the country, while costs would be $36 million.

Republicans had control of Congress, and they didn’t want to raise taxes so that meant more borrowing, $19 million worth. By 1814 the country was looking at another $30 million budget deficit and by 1815 estimates put that at $56 million.

It was clear the war could not continue and both sides sued for peace, meeting in the Flanders city of Ghent in September 1814, just two months before the Congress of Vienna began meeting to settle the Napoleonic Wars.

They talked for five months, and it was agreed a Second Bank of the United States would be created. The Treaty of Ghent was signed on Christmas Eve 1814 to cement the deal.

After that his family, centered in the major financial capitals of Europe, did their best to buy up all the various government bonds right when issued, selling them off to their network of brokers at an inflated price while still paying the initial offering price to the governments.

They cornered markets and saw their wealth grow exponentially. So too did the tightness of their family, as historian Niall Ferguson explains in his book The Ascent of Money:

“As their numbers grew from generation to generation, familial unity was maintained by a combination of periodically revised contracts between the five houses and a high level of intermarriage between cousins or between uncles and nieces.ˮ

“Of twenty-one marriages involving descendents of Nathan’s father Mayer Amschel Rothschild that were solemnized between 1824 and 1877, no fewer than fifteen were between direct descendents.” (Ferguson, p 88)

Most critics lamented the Rothschild’s Jewish heritage, and the family used that anti-semitic thought to further their own ends.

In time it became a shield from their critics, those that knew their true power. That lay in their war-making abilities, a pursuit dependent upon finance and debt.

“Without wars,” Ferguson writes, “nineteenth-century states would have had little need to issue bonds.”

America had issued a lot of bonds during the War of 1812, and total costs for the war were $158 million for the young nation, with the army and navy eating up $90 million of that.

The total cost of interest on the money borrowed came to $16 million and long-term veterans costs equaled $50 million.

Instead of paying off the modest national debt of $45 million that had existed in 1812, the country now was looking at a national debt of $127 million in 1815.

To the Rothschilds, it didn’t matter if the war was won or lost, or even who was fighting.

Either way, there would be debt, and interest on that debt, and they’d profit. Nations would lose, and citizens would suffer, but the bankers would have their way of life.

They had their way with America, for another national bank was created, allowing them unfettered access to the nation’s money supply through their power to control lending and interest rates.

It would take until 1835 for the national debt to be paid off completely, the first and only time that occurred.

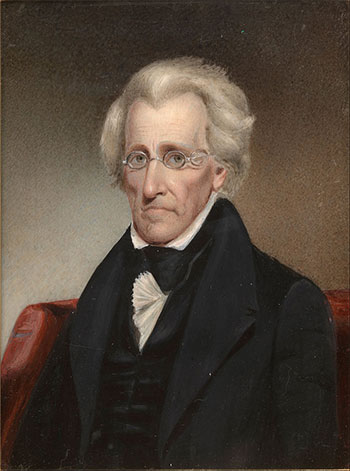

It was President Andrew Jackson that did it, and he was also the person to kill the second Rothschild bank in the country, the Second Bank of the United States.

The Second Bank of the United States had started under another 20-year charter in 1816 and that came to an end in 1836.

Before that, Jackson had consolidated the remaining $75 million of debt held by the states and done everything he could to pay it off as fast as he could, depriving the Rothschild’s of the interest they so thought they deserved.

‟In retaliation for Jackson’s closing of the bank, Rothschild agent Nicholas Biddle ‘cut off funding to the US government in 1842,’ which sent the country into a recession, or panic as they were still called.ˮ (Henderson, p 462)

Jackson was a military man, one who’d won the Battle of New Orleans in the closing days of the War of 1812.

He knew what he was up against, had ran on the 1832 campaign slogan “Jackson and No Bank,” and he prided himself on ‘killing the bank,’ as he was fond of saying of his veto to renew the bank’s charter.

“You are a den of vipers,” Jackson had said of the bankers. “I intend to expose you and by Eternal God I will route you out.”

God may have disproved of the bankers, but the Vatican did not.

In 1831, Pope Gregory XVI borrowed £400,000 from the Rothschilds, or the equivalent of $43 million in 2014 dollars.

James de Rothschild ‟became the official Papal banker,ˮ Gerald Posner writes in his book God’s Bankers, and this proved ‟a lifeline to the church.ˮ

Back in America, Jackson said there would “be a revolution by morning” if the people knew what the bankers were doing to them.

In 1832 he said that “foreign stockholders” controlling our currency were “more formidable and dangerous than the naval and military power of the enemy.” (Henderson, p 461)

This resulted in an assassination attempt on January 30, 1835, though the assassin’s gun misfired. Jackson’s will didn’t, and his desire to see the foreign-owned and controlled bank’s end only intensified.

So did the nation’s, and Jackson’s successor, President John Tyler, also refused to sign a new charter for the bank.

Back in Europe the Vatican became more entwined with the Rothschilds. In 1848 Gregory’s successor, Pope Pius IX, borrowed 50 million francs from the Rothschilds, or $10 million.

By the end of that year it was determined that the Vatican was 142 million francs in debt to the Rothschilds, or about $30 million. This comprised 40% of the church’s total debt.

Unlike the popes, all American presidents were able to keep their financial house in order, even Lincoln when he ordered the printing of Greenbacks during the Civil War instead of borrow from foreign banks or allow another on American soil.

The National Banking Act had been passed in 1863, however, which created yet another private bank, this time under the guise of issuing war bonds. Lincoln said during his second presidential campaign that he’d veto the bill, but an assassin’s bullet took him before he had the chance. (Henderson, p 462)

By 1899 the wealth of the Rothschild family was £41 million, which “exceeded the capital of the five biggest German joint-stock banks put together,” Ferguson tells us. (Ferguson, p 88)

Still, they hungered for more. All the presidents after Lincoln had kept Jackson’s pledge not to have a bank, all that is, until Woodrow Wilson swept into the White House in 1912 on a divided Republican ticket more than a united Democratic ticket.

The following year saw the third and current Bank of the United States form, the Federal Reserve, which was passed with the Federal Reserve Act on December 23 of that year.

Congressman Charles August Lindbergh of Minnesota, the famous aviator’s father, called it the “greatest crime of the ages.”

The Federal Reserve was a private company, and one that had no reserves of currency. Its origins lay in the banking crisis known as the Panic of 1907.

President Theodore Roosevelt had signed the Aldrich-Vreeland Act in 1908 to study the causes of the Panic of 1907.

From it came the National Monetary Commission, which was tasked with investigating what caused these banking panics that were becoming so prevalent in modern society.

The result was a secret meeting with the leading bankers of the day, including Benjamin Strong, adviser to J.P. Morgan and eventual first president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, at Jekyll Island in Georgia, the rich conclave many wealthy Montanans knew so well.

Also called the Millionaires Club, the club was founded in 1886 and included some of the wealthiest families in the country like the Morgans, Rockefellers, and Vanderbilts.

Montana’s Marcus Daly was a member, as was railroad tycoon and patriarch of Montana’s Hi-Line, James J. Hill. Railroad financier E.H. Harriman was another, and together these men benefited from Rothschild banking money when it came to funding their operations and expansion.

These rich industrialists and bankers came up with the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which would become the leading bank of the Federal Reserve System, the institution and framework that was hammered out over those three years following the Panic of 1907.

Now they just had to get the president to sign it the idea into law.

Read the third part of the article

yogaesoteric

February 4, 2020