The Persecution and Resistance of Loic Le Ribault (I)

The creation of a treatment for arthritis and the persecution of its author, France’s foremost forensic scientist

“I shall continue my actions of distributing G5 despite all the opposition. I do it for all those patients for whom I have the opportunity and honor of caring, those who were abandoned by modern medicine which was unable to offer them a cure or who found the allopathic treatments offered worse than the illness itself.” – Loic Le Ribault (April 18, 1947 – June 6, 2007)

“I shall continue my actions of distributing G5 despite all the opposition. I do it for all those patients for whom I have the opportunity and honor of caring, those who were abandoned by modern medicine which was unable to offer them a cure or who found the allopathic treatments offered worse than the illness itself.” – Loic Le Ribault (April 18, 1947 – June 6, 2007)

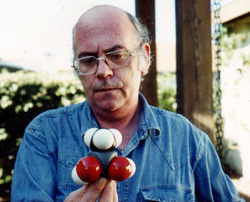

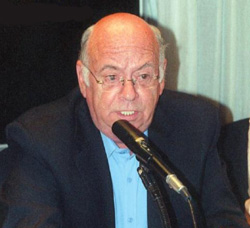

Loic Le Ribault, France’s most renowned forensic scientist (1) and specialist in the study of silica, held court in the dingy surroundings of the Flying Fish pub on the harbor in St Helier, Jersey (Channel Islands). With a Gaelic shrug and in faltering English, he explained how the pub had become his home and his office after he fled France, being persecuted there.

He knew almost everyone in the bar, as he knew the bus drivers, the local shopkeepers and many of the harbors boat owners. He knew them, he said, “because I have treated them, for this illness and that illness. Many of them I have cured with G5”.

Sitting in the Flying Fish, Le Ribault did not seem like a man who had been hounded out of France because he discovered and distributed a treatment for arthritis and a number of other common ailments.

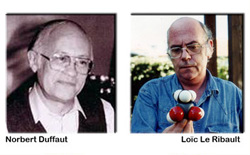

In 1985 while working as an independent forensic scientist for the French judiciary, Le Ribault joined forces with a highly acclaimed research chemist, Professor Norbert Duffaut from the University of Bordeaux. Between them, they hoped to develop their common work on organic silica, a substance which they believed had a wide range of therapeutic uses.

After twelve years work together, perhaps as a consequence of their work on the new therapy, Duffaut was dead, poisoned in suspicious circumstances and Le Ribault himself had suffered two months solitary confinement in a French jail.

Loic Le Ribault appeared quintessentially French. He was phlegmatic and when he was not laughing gently and self-deprecatingly, his rubbery face deflated with the world-weary sadness of a circus clown. In well-worn casual clothes, with white wings of cotton wool hair floating around the bald dome of his head, his lack of fluent English, for which he constantly apologized, made him appear wise but forgetful. Listening to him, you had to keep reminding yourself that over the last years he had lost everything but his mind.

An Early Promise

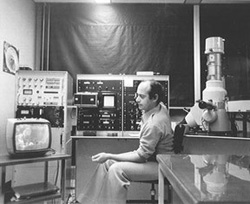

Thirty years ago, still in his twenties, Loic Le Ribault was a precocious young academic, having ground-breaking papers published by the French Academy of Science. At twenty-four, in 1971, he discovered a new function for the electron scanning microscope (ESM) which enabled him to discern the history of grains of sand.

Thirty years ago, still in his twenties, Loic Le Ribault was a precocious young academic, having ground-breaking papers published by the French Academy of Science. At twenty-four, in 1971, he discovered a new function for the electron scanning microscope (ESM) which enabled him to discern the history of grains of sand.

Previously the electron scanning microscope capable at that time of 30,000 magnification had been used in biology and medicine, no one had imagined that it might be used for looking at rocks. Under the electron scanning microscope, Le Ribault found that he could discern the entire history of a grain of sand; where and when it originated, how it was formed, where and how it had been transported, where it had next lodged, how long it had stayed in that place. By the time he had finished his research, he had devised a list of two hundred and fifty criteria by which the history of sand might be diagnosed. The field was later to become so specialized that it would take three years to train a scientist in the technical knowledge to carry out these tests. (2)

Le Ribault’s approach to analysis and detection of sand had some academic and commercial uses but was most clearly an invaluable aid to policing. While still working at university, he was approached by the FBI and became a forensic consultant for them.

Despite this early discovery of a new use for the ESM, Le Ribault found it hard to get work in the universities after he qualified and in 1982, he set up his own national laboratory for electron microscopy, called CARME and quickly became France’s most noted forensic scientist. CARME became the principal laboratory used by the police service, the judiciary and the French Home Office.

Le Ribault was the first to admit that he was not a diplomat, even that he was anarchistic in his view of society. Constant struggles between himself and the French Home Office, seemingly about hegemony, did not endear him to servants of the State. At the height of CARME’s work, Le Ribault was a nationally recognized figure with a high public profile, working and commenting on some of France’s most intriguing criminal, military and political cases. Always a populist, he was much sought after by television, radio and newspapers as well as the French political parties.

“When I had CARME, every week I had articles in the press and on TV, and every French party asked me to be involved with them. On TV and in newspapers, I made information accessible, very often I did lectures in Primary and secondary schools as well as universities.”

Despite a brilliant record as an expert witness, the French Home Office and the police service seemed to have been wary of Le Ribault’s cavalier genius as well as his tacit control of Home Office forensics. He said that the French State frequently referred to him as their scientist and to his laboratory as that of the Home Office.

Despite a brilliant record as an expert witness, the French Home Office and the police service seemed to have been wary of Le Ribault’s cavalier genius as well as his tacit control of Home Office forensics. He said that the French State frequently referred to him as their scientist and to his laboratory as that of the Home Office.

Le Ribault’s career as France’s most eminent forensic scientist came to a sudden end in 1991, when the Home Office decided to integrate their own regional forensic laboratories equipped with electron microscopes. In the following debacle, Le Ribault lost his laboratory, which had employed thirty odd people, and his home which he had mortgaged as surety for the laboratory.

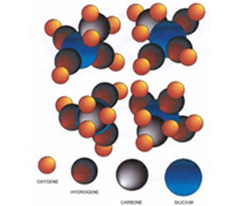

A resilient character, Le Ribault adapted to his new life, lived in the family home and returned to his first love, silica. Back in 1972, while working with sand on the ESM he had made an interesting discovery, a layer of water-soluble amorphous silica which contained micro-organisms covered the surface of some sand grains. He found that these microorganism and the secretions which they left on the sand contained organic silica. Organic silica differs from mineral silica which makes up the majority of the Earth’s crust, in that it contains Carbon and can be readily assimilated by animals.

By 1975, Le Ribault had created a process by which it was possible to recover these deposits from the surface of the sand. All of this work was accepted by the scientific establishment and his papers published by the French Academy of Science.

There had been constant research into organic silica over the previous fifty years and some of this research had raised questions about its therapeutic use. In his early work, as a geologist, Le Ribault had not been following the research into silica and health. But in the early eighties, while working on the organic silica deposits he had found, he immersed his hands in organic silica solution and found that his psoriasis was cured. From then on, Le Ribault’s work became focused in the therapeutic properties of silica.

From Pollutant to Essential Nutrient

Silica is an essential element of living matter. Found in body tissue, the thymus gland, the vascular lining, the adrenal glands, the liver, the spleen, the pancreas and in considerable quantity in hair. With age the body loses its store of organic silica and is unable to replace it from sources outside the body which are predominantly mineral silica.

Silica is an essential element of living matter. Found in body tissue, the thymus gland, the vascular lining, the adrenal glands, the liver, the spleen, the pancreas and in considerable quantity in hair. With age the body loses its store of organic silica and is unable to replace it from sources outside the body which are predominantly mineral silica.

It was originally thought that silica was at worst an environmental contaminant of the human body and at best an element which quickly passed through the body and was excreted. These ideas were based almost entirely upon observations of mineral Silica, which in the form of dust and particles was responsible for a number of serious illnesses such as silicosis.

Silica in mineral form had been used therapeutically, it was however absorbed inefficiently into the human body. It had traditionally gained a place in the pantheon of herbal remedies, being present in Horse’s Tail Fern, and some vegetables.

Work over the years on absorbable mineral and organic silica since the nineteen thirties, showed irrefutably that organic silica could be described as an essential nutrient for both humans and other animals (3). It is necessary for early calcification of bones and animals’ shells, its deficiency has been found to produce alterations and abnormalities in bone growth. It has also been observed that silica plays a part in the makeup of the cells which formed blood vessel walls. Perhaps most importantly, silica has been found to directly affect and form a large part of the connective tissue and cartilage which plays an important part in joints and the illnesses which affect them.

In studies during the nineteen seventies it was found that silica supplementation aided bone and cartilage growth, in 1993, it was reported that treatment with silicon could stimulate bone formation.

By the nineteen nineties, silica formulations were being used by some pharmaceutical companies, on wound dressings and burn dressings because it was recognized that wounds healed more quickly and burns could be stabilized (4, 5).

A Man on The Moon

In 1982, Le Ribault began work with Professor Norbert Duffaut, a chemist and research engineer at the CNRS (The National Centre for Scientific Research) situated at the University of Bordeaux. In 1957, Duffaut had synthesized a molecule of organic silicon which was capable of being absorbed by the human body.

In 1982, Le Ribault began work with Professor Norbert Duffaut, a chemist and research engineer at the CNRS (The National Centre for Scientific Research) situated at the University of Bordeaux. In 1957, Duffaut had synthesized a molecule of organic silicon which was capable of being absorbed by the human body.

Unlike Le Ribault, Duffaut had been using his organic silica as a therapeutic agent, treating patients since his first discoveries in the nineteen fifties. Like Ribault, Duffaut paid little attention to the academic papers on organic silica, convinced that he was ahead of the field.

When Le Ribault first met Duffaut, he had been treating people for years and he was well known in the South West of France and even in Paris. Duffaut had created NDR, the Norbert Duffaut Remedy, and had manufactured many liters, for thousands and thousands of patients. Whether to avoid the regulatory agencies, or simply out of sheer cussedness, Duffaut refused to keep any records of his transactions. “He absolutely refused to keep a record of anything which he did”, said Le Ribault. He would say: “We are right, we will win in the end”.

In 1958 Duffaut had begun successful clinical work with Dr. Jacques Janet, a gastroenterologist. He had also begun treating people, very successfully, for arthritis. Duffaut was, however, sure that cardiovascular work and blood circulation work were the most important therapeutic goals in relation to organic silica. In the nineteen sixties, Duffaut worked with Dr. Rager, a cardio-vascular surgeon, who used organic silica for post-operative recovery. In 1967 Rager was awarded the J Levy Bricker Prize by the French Academy of Medicine for his work on the use of organic silica in the treatment of man. Rager’s work also determined that organic silica helped cancer patients withstand chemotherapy.

Le Ribault and Duffaut had more than a passion for silica in common. Duffaut, in his sixties, was considered by many to be an impossibly difficult man. Le Ribault, speaking with sadness but with his usual humor, said of Duffaut:

“He was less diplomatic than me! A lot less diplomatic than me! Can you imagine? He was impossible. He considered that the system was made up of stupid people, he was right of course, but he said it to them on many occasions. He was eccentric, very much an individualist. I guess I was the only person able to work with him.”

Like Le Ribault, Duffaut also used humor to shield himself from the deeper conflicts. “Duffaut was a very, very clever man, really a genius, a high level chemist who was always singing and joking and smiling, all the day long – every day!” Le Ribault fondly remembered an unmarried man, utterly immersed in his scientific work, cut off from the humdrum intercourse of the everyday world to such an extent, Le Ribault joked that he was “on the moon” for much of the time.

Like Le Ribault, Duffaut also used humor to shield himself from the deeper conflicts. “Duffaut was a very, very clever man, really a genius, a high level chemist who was always singing and joking and smiling, all the day long – every day!” Le Ribault fondly remembered an unmarried man, utterly immersed in his scientific work, cut off from the humdrum intercourse of the everyday world to such an extent, Le Ribault joked that he was “on the moon” for much of the time.

When Le Ribault met Duffaut, he had been testing his synthetic organic silica molecule therapeutically for fifteen years and had frequently offered his invention free to the French State and its medical research organizations. All his approaches had been met with an utter and seemingly deliberate silence.

In 1985, Duffaut and Le Ribault took out an international patent to protect the therapeutic use of organic silica. And in 1987, like many other publicly concerned scientists outside the pharmaceutical companies, they made representations to the French Minister of Research, asking that he consider their discovery for trials in cases of AIDS-related illnesses. So determined were they to force recognition of the health-giving qualities of silica on the Government that they had their request, and the evidence to support it, legally served on the Minister. Duffaut and Le Ribault receive no reply.

In November 1993, Duffaut, was found dead in his bed by neighbors who noticed he had not been out of his house. Despite the fact that Duffaut was in his early seventies and had died in bed, a post-mortem was held and potassium cyanide in his system. Although no letter was found and despite the fact that witnesses had seen Duffaut the night before in good spirits, the police concluded that he had committed suicide.

Initially, Le Ribault accepted the suicide of his colleague but has since begun to have doubts. His principle doubt was that Duffaut, a highly trained chemist would have chosen Potassium Cyanide as a vehicle for suicide, knowing that it would occasion an incredibly painful death. Duffaut’s writing prior to his death did show a despondency clearly brought about by continual disappointment and frustration. His last notes contained the sentence. “The authorities have condemned my discovery out of hand without having even tested it.”

Practice Makes Perfect

As his work progressed with Duffaut, Loic Le Ribault found that there was, in his mind, less and less academic considerations about the therapeutic uses of organic silica. He was preoccupied throughout the eighties and early nineties with trying to make the organic silica Duffaut had been using for compresses, drinkable.

As his work progressed with Duffaut, Loic Le Ribault found that there was, in his mind, less and less academic considerations about the therapeutic uses of organic silica. He was preoccupied throughout the eighties and early nineties with trying to make the organic silica Duffaut had been using for compresses, drinkable.

“One of the most serious difficulties, was trying to make G5 drinkable. The solution we had created was slightly toxic, alright for using on the skin but not for drinking. Perhaps no more toxic than red wine, but I didn’t want it to be at all toxic.”

When Le Ribault first make his therapeutic discovery, he was skeptical. However, after two or three years working with a number of doctors who used the discovery on patients and after his years of work with Duffaut, he decided that he was in a position to send files to the Ministry of Health, asking them to carry out trials on the basis of free solutions which would be supplied by him. He did not receive an answer to his many communications. The private treatment of patients, did not fit with either Le Ribault or Duffaut’s ideas about health care, both wished that the French government would take up the idea of organic silica. By the mid-nineties, between them, Le Ribault and Duffaut had treated well over 10,000 people, firstly with organic silica poultices and then with a drinkable tonic solution.

Determined to make his findings of public consequence, Le Ribault arranged personal meetings in America with the Chairmen of the main pharmaceutical laboratories; he travelled to visit executives in Canada and the length and breadth of France. All the people he met showed interest and most told him that they would be in touch within weeks, as he said later “I have been waiting fifteen years for a reply.” One executive of a pharmaceutical company offered him £1,000,000 just to bury his discovery.

Regulating Molecules

At the end of 1994, Le Ribault, now working on his own with an organic silica molecule suspended in water, which he called G5, stepped up production and distribution to people with health problems. It was Le Ribault’s case that as a natural nontoxic substance, G5 did not need a license; he saw it as a tonic or dietary supplement.

At the end of 1994, Le Ribault, now working on his own with an organic silica molecule suspended in water, which he called G5, stepped up production and distribution to people with health problems. It was Le Ribault’s case that as a natural nontoxic substance, G5 did not need a license; he saw it as a tonic or dietary supplement.

The problem of who pays to test a novel medical product, developed outside the pharmaceutical companies, has become a serious issue in America and European countries. On the boundaries of different kinds of medical treatment, a constant war is being waged. Trade and practice with non-pharmaceutical treatments are constantly attacked by big companies. The most common aggressors in this war of attrition are the pharmaceutical companies. With close allies in the regulatory agencies, university research departments, hospital Trusts and the media, a strategy of attrition whittles away at the number of medicinal plants which are legally available and constantly attempts to restrict the availability of vitamins and food supplements.

The highly capitalized pharmaceutical companies can afford to compete with each other, paying hundreds of thousands, often millions, of pounds to carry out trials and then thousands of pounds for preparatory paper work so that their cases can be put before the regulatory agencies. When they have obtained licenses, aggressive marketing strategies, regulatory protection and sometimes ‘dirty tricks’ ensure competitive ascendancy.

Herbalists, homoeopaths, nutritional therapists and those producers and practitioners who work with non-pharmaceutical treatments, unable to raise the money or hire sympathetic laboratories to carry out trials, are forced to market and use their treatments with one hand tied behind their back, unable to advertise any health-enhancing effects of any of their therapies.

Some few innovators are fortunate in achieving special discretionary awards from the FDA in America, or the Medicine Controls Agency or MAFF in Britain, which exempt their natural therapies from the needs of a license (6).The career of these odd treatments is irregular and haphazard and is probably dependent upon whether or not there is competition from pharmaceutical products.

The competitive, financial and professional censorship by multinationals and doctors of novel natural health therapies, at this lower end of the health care market, has inevitably spawned ‘illegal’ businesses and made criminals out of some doctors, scientists and therapists. But perhaps more importantly, in an odd way the pharmaceutically protective regulations and their policing have also created criminals out of many patients. By denying patients the freedom to choose their own treatments, the law and the regulatory agencies have forced some patients into a culture of underground health care.

It was into this maelstrom of pharmaceutical protection, pharmaceutical company biased regulation and confused policing, that Le Ribault, tired of the invisibility of the authorities and angered by the odd death of his colleague, launched G5 in 1994. Le Ribault’s determination to confront the big companies and the regulatory agencies was to bring his life collapsing about him.

Soon after Le Ribault began to distribute G5, in June 1995, Jean-Michel Graille, a journalist on Sud-Ouest Dimanche, approached him and asked if he could write about his discovery. Ten years previously, Graille had written a book called Dossier Priore; une nouvelle affaire Pasteur? (7) After getting agreement from his editor, Graille attached himself to Le Ribault for four months, observing his work as a scientist, innovator and now entrepreneur. After some initial skepticism, Graille became completely convinced of the therapeutic effects of Le Ribault’s discovery. In October 1995, Sud-Ouest Dimanche published, across five pages of their magazine, a detailed account of Le Ribault’s work and the suppression of his findings.

The unbelievable results of this article were to drag Le Ribault into an uncontrollable conflict with the judiciary and other, more hidden, forces. In the days following publication, Le Ribault received 35,000 phone calls, letters and visiting patients. He was obliged to rent a hotel and call scientists, doctors and personal friends to help sort out the calls and callers. Sud-Ouest Dimanche had to hire eight receptionists to answer calls. The local telephone service broke down and the phone lines to police stations and post offices were blocked for days. In the three months that followed the article, Le Ribault did his best to treat the thousands of people who converged on the area, seeking help. He says now that pharmacists in the area lost around 35% of their turnover in this tidal wave.

The unbelievable results of this article were to drag Le Ribault into an uncontrollable conflict with the judiciary and other, more hidden, forces. In the days following publication, Le Ribault received 35,000 phone calls, letters and visiting patients. He was obliged to rent a hotel and call scientists, doctors and personal friends to help sort out the calls and callers. Sud-Ouest Dimanche had to hire eight receptionists to answer calls. The local telephone service broke down and the phone lines to police stations and post offices were blocked for days. In the three months that followed the article, Le Ribault did his best to treat the thousands of people who converged on the area, seeking help. He says now that pharmacists in the area lost around 35% of their turnover in this tidal wave.

The article had other, more sinister results. As soon as it came out, Le Ribault claims, other newspapers were warned not to publish more articles. He received frequent death threats, his house was burgled, and his collaborators were threatened. One middle aged woman, who had been his aide for many years, was held hostage for an hour, in Le Ribault’s house, attacked and seriously wounded. Le Ribault and his colleague knew the assailant, a Marseilles criminal who had tried to force Le Ribault to give him a franchise on G5. The police did nothing when they were informed.

Either by conspiracy, or simple criminal opportunism, companies suddenly began to spring up claiming to be using organic silica for health therapies. Many of these companies used Le Ribault and Duffaut’s names, their photographs and even their fake signatures. Illegal advertising material flooded the market using quotes from Graille’s article. Le Ribault later saw public laboratory analysis of these products, which he says were either water, mineral silica or dangerous, unstable synthesis of organic silica.

Le Ribault had nothing to do with these ventures, but in January 1996, after a number of apparently genuine complaints had been received about these fake products, the Order of Doctors and the Order of Pharmacologists, the professional institutions which protect the interests of doctors and pharmacists throughout France, laid a complaint against Le Ribault before an examining Magistrate. The complaint cited the illegal practices of medicine and pharmacology. Initially, with the naiveté of one divorced from politics, Le Ribault was pleased that the complaint had been lodged; “this was something which I had been looking for, something which I expected. I thought that now the court would be obliged to instruct someone to make the tests.” Le Ribault had about six months grace before the hearing was due.

In the middle of these assaults, Le Ribault was unable to see the wood for the trees, unable to perceive that an all-out campaign had begun, the objective of which was to put an end to the therapeutic use of his discovery. His confusion and unhappiness were deepened by the death of Jean-Michel Graille in April 1996. Graille, perhaps his most articulate public supporter died suddenly and unexpectedly, aged 50, of a stroke, while relaxing in his garden.

Going to Antigua

Le Ribault looked back upon his own unworldliness and the dangers which he had faced with some mirth. His most self-deprecating story, in an otherwise dark melodrama, is the story of how he came to end up in Antigua (Caribbean island).

Le Ribault looked back upon his own unworldliness and the dangers which he had faced with some mirth. His most self-deprecating story, in an otherwise dark melodrama, is the story of how he came to end up in Antigua (Caribbean island).

Following the publication of Graille’s story, many individuals sent money, in total £500,000, to enable Le Ribault to build a clinic. Amongst the sharks who suddenly appeared wanting a piece of the action, were a group of businessmen who sought to advice Le Ribault on the setting up of a company. He took their advice, transferring the control of the new company to nominee shareholders suggested by the group.

After some discussion and planning, Le Ribault was told that contacts had been made and bank accounts opened, for him to set up his clinic in Antigua. Le Ribault’s passport had been stolen when his house was burgled. With his fare paid by the company, he set off for Antigua, undercover, via the French protectorate of Martinique. It was only when he landed in Antigua and found no one there to meet him that he began to realize he was alone on the other side of the world with no passport, no English language, no funds or friends.

“I was told that the Prime Minister himself would be waiting for me in Antigua with a diplomatic passport and I would be free to travel. I was told that there was a bank account for me and everything was ready to start the clinic. Of course, when I got there, no one was waiting for me. I had only three small bottles of G5.”

As resourceful as ever, Le Ribault began treating the rich, elderly and often arthritic boat owners as they returned from their days sailing around the coast. At the end of his first day’s work, he had a hundred pounds and appointments for the whole of the following week. A week later, he had enough money to travel back to France, had he wanted to.

By his own perseverance, Le Ribault made the contacts himself which should have been made for him in Antigua.

“I got permission from the Prime Minister to start a health center. I had two kinds of patients, local patients, who have no money and I never asked money from them, they paid what they were able for their treatment; they brought me fish and vegetables and other things. In the evenings I went to the big hotels filled with the millionaire tourists, to cure them of their sunburn. Every day I had between twenty and forty tourists to cure. G5 gets rid of the pain of sunburn within five minutes and within an hour cures the sunburn itself. I also taught the barmen in the hotel bars how to use G5, so every evening the barmen applied poultices to the tourists.”

During his time in Antigua, Le Ribault pursued an embittered relationship with his homeland. When he received regulatory agreement to produce and use G5 on Antigua, he made sure that the French press raised awkward questions about the situation in France.

Le Ribault’s strategy of embarrassment was to cost him dear. Two days after the issue was raised in the French newspapers, the French police raided the home of his 85 years old mother and questioned her for five hours. His mother, who had been fit and healthy before the interrogation, fell ill that evening. She never recovered her health and died two weeks later.

The police told Ribault’s mother that there was now a warrant out for Le Ribault’s arrest and they were searching for documents not only about G5 but also about Ribault’s forensic laboratory CARME. Le Ribault thought that when his trouble began to develop over G5, the police became concerned about the possible leaking of information about sensitive police cases.

The police told Ribault’s mother that there was now a warrant out for Le Ribault’s arrest and they were searching for documents not only about G5 but also about Ribault’s forensic laboratory CARME. Le Ribault thought that when his trouble began to develop over G5, the police became concerned about the possible leaking of information about sensitive police cases.

Stranded in the Caribbean, Le Ribault was deeply saddened by the death of his mother and angered by what appeared to be a gratuitous police strategy. He had not hidden himself in Antigua: the judge who was dealing with the complaint against him, had his fax, phone number and address, “The police knew that my mother was very old and tired. When she died, I suppose they reckoned that I would turn up at the funeral and they would be able to arrest me.”

In November 1997, Le Ribault felt obliged to go back to France to recover the personal and work documents which he needed to continue work in Antigua. Knowing that there was a warrant out for his arrest, he decided to return covertly. “It was my intention to show the Antiguan agreements to people in France in the hope that I could get a similar one there. I visited doctors and a number of other sympathizers who I thought could push my case forward.”

Notes and References

1. Between 1982 and 1991, Le Ribault gave evidence in over a thousand cases, helping to convict 800 defendants mainly of murder and other violent crimes. He introduced not only the electron scanning Microscope to French criminal forensic work, but also the high technology mobile laboratory constructed in the back of a van. He published over fifty papers in journals about different aspects of forensic work and was the subject of hundreds of newspaper articles.

2. Le Ribault received his doctorate in Geology and as a result of his early work with electron microscopy, he got to know silica so well, that he could determine the geological history of a grain of sand. In his first book The History of a Grain of Sand, told this very story. When he was first approached by the FBI to test three blinded sand samples, he was able to tell them the exact location in the world from which they had been collected, that one sample had been gathered from the bonnet of a car and that another had been in the vicinity of an explosion in Beirut.

3. Carlisle, Edith M. Silicon as an essential element. Environmental and Nutritional Science, School of Public Health, University of California, Los Angeles. Newer Candidates for essential trace elements. Federation proceedings Vol. 33. No 6. June 1974.

4. Silastic Gel and elastomer in the cicatrization of wounds in the rabbit, Aubert, J.P., Magolon, G. J.Chir. Paris. 1993 Dec; 130 (12): 533-8.

5. Treatment of burn wounds and wounds healing with secondary tightening using dressings with aerosil. Mishchuk I.I., Nagaichuk, V.I., Gomon, N.L., Berezovskaia, Z.B., Ossovskaia, A.B. Klin. Khir. 1994 (4) : 21-2)

6. See for example the case of methyl sulphonyl methane (MSM) which has a remarkable similarity to the case of G5. MSM is an organic Sulphur, found in meat fish and fresh vegetables and used originally, in synthetic form as an animal nutrient for stiff joints but now sold as the food supplement Supersulf. Dr Robert Hershier who synthesized the compound, has always refused to deal with the pharmaceutical companies because he knows that the substance would be withdrawn and subjected to lengthy trials, which would in turn increase the price of MSM. Dr Hershier, has however managed to get his therapy passed by the American Food and Drugs Administration as a food supplement.

7. Jean-Michel Graille (1984) Dossier Priore; une nouvelle affaire Pasteur? Editions Denoel, Paris.

During the Second World War, Priore, an officer in the Italian Navy, discovered by chance that certain forms of radiation were able to cure cancer. Following the war, Priore went to France and built a machine to generate radiation and with which he began to get good results on cancer patients. His work was watched, supported and verified, with great interest and excitement by the French political establishment. But when an ‘independent’ scientific report was made of his work by cancer specialists, its conclusions were falsified. Priore died in 1983.

Read the second part of this article

yogaesoteric

March 24, 2017

Also available in:

Română

Română