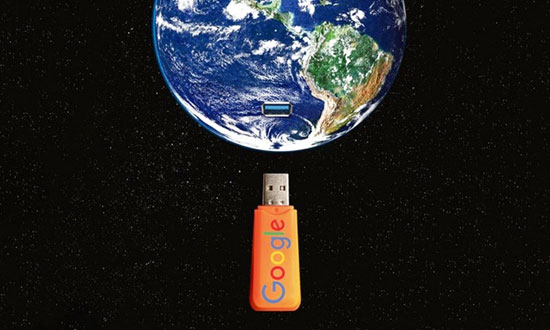

Google’s Earth: How the tech giant is helping the deep state spy on us (1)

The internet surrounds us. It mediates modern life, like a giant, unseen blob that engulfs the modern world. There is no escape, and, as Larry Page and Sergey Brin so astutely understood when they launched Google in 1998, everything that people do online leaves a trail of data. If saved and used correctly, these traces make up a goldmine of information full of insights into people on a personal level as well as a valuable read on larger cultural, economic and political trends.

Google was the first internet company to fully leverage this insight and build a business on the data that people leave behind. But it wasn’t alone for long. It happened just about everywhere, from the smallest app to the most sprawling platform.

Uber, Amazon, Facebook, eBay, Tinder, Apple, Lyft, Foursquare, Airbnb, Spotify, Instagram, Twitter, Angry Birds – if you zoom out and look at the bigger picture, you can see that, taken together, these companies have turned our computers and phones into bugs that are plugged in to a vast corporate-owned surveillance net-work. Where we go, what we do, what we talk about, who we talk to, and who we see – everything is recorded and, at some point, leveraged for value. Google, Apple and Facebook know when a woman visits an abortion clinic, even if she tells no one else: the GPS coordinates on the phone don’t lie. One-night stands and extramarital affairs are a cinch to figure out: two smartphones that never met before suddenly cross paths in a bar and then make their way to an apartment across town, stay together overnight, and part in the morning.

They know us intimately, even the things that we hide from those closest to us. In our modern internet ecosystem, this kind of private surveillance is the norm. It is as unnoticed and unremarkable as the air we breathe. But even in this advanced, data-hungry environment, in terms of sheer scope and ubiquity, Google reigns supreme.

As the internet expanded, Google grew along with it. No matter what service it deployed or what market it entered, surveillance and prediction were cooked into the business. The amount of data flowing through Google’s systems is staggering. By the end of 2016, Google’s Android was installed on 82% of all new smartphones sold around the world, and by mid-2017 there were more than 2 billion Android users globally.

Google also handles billions of searches and YouTube plays daily, and has a billion active Gmail users, meaning it had access to most of the world’s emails. Some analysts estimate that 25% of all internet traffic in North America goes through Google’s servers. The company isn’t just connected to the internet, it is the internet.

Google has pioneered a whole new type of business transaction. Instead of paying for its services with money, people pay with their data. And the services it offers to consumers are just the lures, used to grab people’s data and dominate their attention – attention that is contracted out to advertisers. Google has used data to grow its empire. By early 2018, Google’s parent company, Alphabet, had 85,050 employees, working out of more than 70 offices in 50 countries. The company had a market capitalisation of $727bn at the end of 2017, making it the second most valuable public company in the world, beaten only by Apple, another Silicon Valley giant. Its profits for the first quarter of 2018 were $9.4bn.

Google co-founders Larry Page, left, and Sergey Brin in 2004

Meanwhile, other internet companies depend on Google for survival. Snapchat, Twitter, Facebook, Lyft and Uber have all built multi-billion-dollar businesses on top of Google’s ubiquitous mobile operating system. As the gatekeeper, Google benefits from their success as well. The more people who use their mobile devices, the more data it gets on them.

What does Google know? What can it guess? Well, it seems just about everything. “One of the things that eventually happens … is that we don’t need you to type at all”, Eric Schmidt, Google’s former CEO, said in a moment of candor in 2010. “Because we know where you are. We know where you’ve been. We can more or less guess what you’re thinking about.” He later added: “One day we had a conversation where we figured we could just try to predict the stock market. And then we decided it was illegal. So we stopped doing that.”

It is a scary thought, considering that Google is no longer a cute startup but a powerful global corporation with its own political agenda and a mission to maximise profits for shareholders. Imagine if Philip Morris, Goldman Sachs or a military contractor like Lockheed Martin had this kind of access.

Not long after Brin and Page incorporated Google, they began to see their mission in bigger terms. They weren’t just building a search engine or a targeted advertising business. They were organising the world’s information to make it accessible and useful for everyone. It was a vision that also encompassed the Pentagon.

Even as Google grew to dominate the consumer internet, a second side of the company emerged, one that rarely got much notice: Google the government contractor. As it turns out, the same platforms and services that Google deploys to monitor people’s lives and grab their data could be put to use running huge swaths of the US government, including the military, spy agencies, police departments and schools. The key to this transformation was a small startup now known as Google Earth.

In 2003, a San Francisco company called Keyhole Incorporated was on the ropes. With a name recalling the CIA’s secret 1960s “Keyhole” spy satellite programme, the company had been launched two years earlier as a spinoff from a videogame outfit. Its CEO, John Hanke, told journalists that the inspiration for his company came from Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, a cult science-fiction novel in which the hero taps into a programme created by the “Central Intelligence Corporation” called Planet Earth, a virtual reality construct designed, as the book describes, to “keep track of every bit of spatial information that it owns – all the maps, weather data, architectural plans, and satellite surveillance stuff”.

Keyhole had its roots in videogame technology, but deployed it in the real world, creating a programme that stitched satellite images and aerial photographs into seamless 3D computer models of the Earth that could be explored as if they were in a virtual reality game world. It was a groundbreaking product that allowed anyone with an internet connection to virtually fly over anywhere in the world. The only problem was Keyhole’s timing: it was a bit off. It launched just as the dotcom bubble blew up in Silicon Valley’s face. Funding dried up, and Keyhole found itself struggling to survive. Luckily, the company was saved just in time by the very entity that inspired it: the CIA.

In 1999, at the peak of the dot-com boom, the CIA had launched In-Q-Tel, a Silicon Valley venture capital fund whose mission was to invest in start-ups that aligned with the agency’s intelligence needs. Keyhole seemed a perfect fit.

The CIA poured an unknown amount of money into Keyhole. The investment was finalised in early 2003, and it was made in partnership with the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, a major intelligence organisation with 14,500 employees and a $5bn budget, whose job was to deliver satellite-based intelligence to the CIA and the Pentagon. Known as the NGA, the spy agency’s motto was: “Know the Earth … Show the Way … Understand the World”.

The CIA and NGA were not just investors; they were also clients, and they involved themselves in customising Keyhole’s virtual map product to meet their own needs. Months after In-Q-Tel’s investment, Keyhole software was already integrated into operational service and deployed to support US troops during Operation Iraqi Freedom, the shock-and-awe campaign to overthrow Saddam Hussein. Intelligence officials were impressed with the “videogame-like” simplicity of its virtual maps. They also appreciated the ability to layer visual information over other intelligence. The possibilities were limited only by what contextual data could be fed and grafted on to a map: troop movements, weapons caches, real-time weather and ocean conditions, intercepted emails and phone call intel, and mobile phone locations.

Keyhole gave intelligence analysts, field commanders, air force pilots and others the kind of capabilities we take for granted today when we use digital mapping services on our computers and smartphones to look up restaurants, cafes, museums, traffic or subway routes.

Military commanders weren’t the only ones who liked Keyhole. So did Sergey Brin. He liked it so much that he insisted on personally demoing the app for Google executives. According to an account published in Wired, he barged in on a company meeting, punched in the address of every person present, and used the programme to virtually fly over their homes.

In 2004, the same year Google went public, Brin and Page bought the company outright, CIA investors and all. They then absorbed the company into Google’s growing internet applications platform. Keyhole was reborn as Google Earth.

The purchase of Keyhole was a milestone for Google, marking the moment the company stopped being a purely consumer-facing internet company and began integrating with the US government. When Google bought Keyhole, it also acquired an In-Q-Tel executive named Rob Painter, who came with deep connections to the world of intelligence and military contracting, including US Special Operations, the CIA and major defence firms, among them Raytheon, Northrop Grumman and Lockheed Martin. At Google, Painter was planted in a new dedicated sales and lobbying division called Google Federal, located in Reston, Virginia, a short drive from the CIA’s headquarters in Langley. His job was to help Google grab a slice of the lucrative military-intelligence contracting market. Or, as Painter described in contractor-bureaucratese, “evangelising and implementing Google Enterprise solutions for a host of users across the intelligence and defence communities”.

Read the second part of this article

yogaesoteric

February 8, 2019