‘Asbestos of the Sky’ – The Aviation Industry’s Darkest Coverup

Are our airplanes really as safe and health as they are marketed to be?

The aviation industry hangs its hat on air travel being “the safest way to travel.” The truth, however, is that it has harbored a dark secret since its inception: it’s poisoning its passengers and crew due to deeply flawed aircraft design, de-prioritizing safety in favor of profit.

In flight, every crew member and passenger relies on an air supply. The assumption, of course, is that this air is filtered, if not fresh. Perhaps you have sensed (and promptly dismissed) that there may be quality control issues around cabin air. The problem goes further than that, however, and astoundingly, this is not by accident, but by design.

What’s more concerning is the fact that the industry has known about this completely preventable health hazard for at least 40 years, but no attempts have been made to filter this cocktail of hundreds of chemicals (including organophosphates in the same category as toxic nerve agents like Sarin) out of the cabin air before travelers are forced to breath them in. Nor has the root cause of the problem – unsafe aircraft design and the deprioritization of human safety – been effectively addressed.

A history of cabin air supply

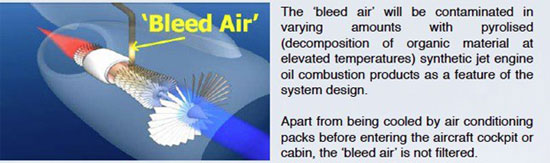

Essentially, the problem comes from the need to supply the jet airliners with warm compressed air while flying at high altitudes. In order to do so, all planes used by commercial airlines since 1963 inject the cabin with air directly from the compressors of their jet engines in what is known as “bleed air.” In the 50s, engineers designed airplanes which pulled fresh air into the cabin, but this “modification” was deemed too costly by decision-makers at the time. As a result of poor design, every breath that the crew and passengers take today, consists of a 50/50 mix of recirculated cabin air and bleed air, the latter of which contains a wide range of synthetic chemicals, such as tricresyl phosphate (TCP or TOCP), an organophosphate which is highly neurotoxic to humans. In fact, the World Health Organisation stated in 1990 that “Because of considerable variation among individuals in sensitivity to TOCP, it is not possible to establish a safe level of exposure” and “TOCP are therefore considered major hazards to human health.”

And so, with the exception of a single aircraft – the new Boeing 787, where cabin air is taken directly from the atmosphere with electrically powered compressors – all flights today involve a high risk of exposure to these neurotoxic chemicals. When you consider there are about 100,000 flights a day (only 5% of which occur on “safe” Boeing 787s), with at least 1 in 100 flights experiencing a major “fume event,” this amounts to the health endangerment of millions of daily passengers.

Entire advocacy organizations exist which are dedicated to exposing the truth about the dangers of toxic airplane air, and pressuring the industry to initiate reform. One such group Aerotoxic Association, which discusses the bleed air problem in greater detail on its website: “Bleed air comes from the compressor section of the jet engine, which has to be lubricated. Jet engines mostly have ‘wet seals’ to keep the oil and air apart, which cannot be 100% effective. Furthermore these seals, like any mechanical component, slowly wear out and their effectiveness gradually declines. This wear can occur more rapidly when the engine is working hard, such as climbing under full throttle. They may also fail suddenly and will then let a significant amount of oil into the very hot compressed bleed air, resulting in fumes and/or smoke entering the cabin. This is known as a ‘fume event’.

There are no filters in the bleed air supply to stop this happening. Note that the oil used to lubricate jet engines is not based on petroleum hydrocarbons, as are lubricants for internal combustion engines used in motor cars, outboard motors, tractors etc. Jet engines operate at much higher temperatures and, therefore, use special synthetic chemicals as oil. They also contain organophosphate additives as antiwear agents and other aromatic hydrocarbons as antioxidants. Some of the oil gets partially decomposed, i.e. chemically altered (‘pyrolysed’) due to the high temperatures in the engine.”

Watch the teaser for the new documentary Unflitered Breathed In – The Truth about Aerotoxic Syndrome.

A complex toxicological assault

Since at least 1977, with the first documented case of a C-130 Hercules navigator becoming incapacitated after breathing contaminated cabin air, the aviation industry’s secret has remained hidden… One thing that has worked in their favor is the common belief that the fatigue, malaise, and similar complaints experienced after a flight are caused by “jet lag”; presumably solely a byproduct of “disrupted circadian rhythms,” (medically referred to as desynchronosis) and not the 800lb gorilla of neurotoxic organophosphate exposures sitting next to every passenger on each flight.

This is not to say alterations in bodily rhythms and other “natural” factors like cosmic radiation, dehydration, and the fact that the cabin is pressurized at between 6,000-8,000 feet (which keeps oxygen levels dangerously low), do not play a significant role. They certainly do. But the problem is that the chemical exposures are rarely if ever identified as a problem. When you also figure in the routine use of pesticides in planes, and the subsequent “toxic soup” of hydrocarbons and synthetic chemicals created, the toxicological synergy amplifies the exposure problem far beyond what would be expected if one focuses only on one chemical.

One can only imagine the cumulative role these exposures have had on the notoriously poor health of airline crew, as well. Clearly, there are highly practical justifications for the industry “cover-up,” as the legal liability for the damage already done to the health and well-being of aircrew alone would be astronomical.

What are the symptoms of aerotoxicosis?

In October 2000, the truth started to emerge with the publication of a seminal study titled Aerotoxic Syndrome: Adverse health effects following exposure to jet oil mist during commercial flights authored by Dr Harry Hoffman, Professor Chris Winder and Jean Christophe Balouet, Ph.D. In the study, the researchers introduce aerotoxic syndrome as a newly identified occupational health condition. They focused on 10 case reports of airline crew who experienced a so-called “fume event,” and subsequent health problems.

The following basic symptoms were identified following single or short term exposures: “Blurred or tunnel vision, disorientation, memory impairment, shaking and tremors, nausea/vomiting, paresthesias, loss of balance and vertigo, seizures, loss of consciousness, headache, lightheadedness, dizziness, confusion and feeling intoxicated, breathing difficulties (shortness of breath, tightness in chest, respiratory failure), increased heart rate and palpitations, nystagmus, irritation (eyes, nose and upper airways).”

Symptoms from long term low level exposure or residual symptoms from short term exposures include: “memory impairment, forgetfulness, lack of coordination, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, respiratory problems, chest pain, severe headaches, dizziness and feeling intoxicated, weakness and fatigue (leading to chronic fatigue), exhaustion, increased heart rate and palpitations, numbness (fingers, lips, limbs), hot flashes, joint pain, muscle weakness and pain, salivation, irritation (eyes, nose and upper airways), skin itching and rashes, skin blisters (on uncovered body parts), signs of immunosupression, hair loss, chemical sensitivity leading to acquired or multiple chemical sensitivity.”

Clearly, if these symptoms are indeed caused by exposure to “bleed air,” or exaggerated “fume events,” these chemicals have the ability to cause profound damage to the human body, particularly the nervous and immune systems.

A 40-Year Long Cover Up Now Exposed

Considering aircraft pilots are continually exposed to jet engine chemicals that can even be found in their blood, the industry lacks any reasonable justification for continuing to ignore the problem. Compromising the neurological fitness of pilots should be taken as seriously as a mechanical defect in the plane. Pilots, after all, are essential to keeping the plane safely in the air.

And significant exposures are not a rare occurrence. A 2007 report by the UK Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment (COT) accepts that fume events occur on 1 flight in 100. The Aerotoxic Association offers a qualification of this statistic, indicating the problem is likely even worse: “However, on some aircraft types crews report that they experience fumes to some degree on every flight and as the definition of ‘fume event’ is not agreed upon, it makes it impossible to give a true figure.”

Under-reporting is epidemic, due to the fact that modern jet aircraft have no chemical sensors installed, and only visible smoke is officially reported in the flight log. Technically, the noses of aircrew are the only detectors being used, and background levels of contamination may not be detectable by smell at all. Likely the most toxic of the hundreds of chemicals present in the bleed air, the organophosphate TCOP, in fact, is odorless. It’s a sad fact, but a U.S. Attorney Alisa Brodkowitz and aerotoxic syndrome expert once correctly opined: “…the only thing filtering this toxic soup out of the cabin are the lungs of the passenger and crew.”

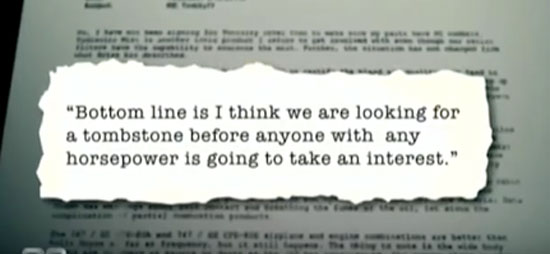

60-minutes obtained an internal memo from the Boeing aircraft company dated 2007 [watch minute 13:00 of the 60 minutes episode below]. It’s all about toxic air. Excerpts from the report written by a frustrated senior Boeing inspector reveal a well recognized problem within the company:

“Some of the events have been significant, in that the crew reported blue smoke with defined waves in smoke.”

“Who knows what the by-products are in hot synthetic turbine oil? The data sheet has warnings about breathing the fumes.”

60 minutes describes the most startling passage, which “ends on a chilling note. That lives need to be lost before Boeing will act.”:

That tombstone, unfortunately, already exists. Richard Westgate, British Airlines pilot, died at 43 after constantly being exposed to fume events. Doubtlessly, many other aircrew and passengers have suffered a similar fate.

Want Things To Change? It’s Up To You and Me

As we mentioned above, the only exception is Boeing’s new 787, a long haul aircraft serving non-stop, inter-continental travel, with few exceptions. Not surprisingly, Boeing does not feature the “clean air” design of these planes in its marketing copy. Bringing attention to this feature would also bring attention to the widespread problem, which all of its other aircraft participate in. Despite this, advocacy organizations have publicly congratulated Boeing on its decision to create a non-toxic alternative. For instance, in 2014, The Global Cabin Air Quality Executive (GCAQE) which represents more than 800,000 airline staff and consumers, put out a press release titled, “Only The Boeing 787 Provides Passengers And Crews With Clean Breathing Air.”

The development and existence of the Boeing 787 represents a tacit acknowledgment of the industry wide problem discussed in this article, and is a step towards a permanent solution. But the vast majority of planes are still in the technological dark ages, with awareness of the extent of the problem and danger only starting to trickle into consciousness.

It will be consumers and non-governmental advocacy organizations that will force the industry and its regulators to make this issue a priority. If only one airline made the step of addressing the problem, it would see huge support by an increasingly educated consumer base.

Short of redesigning existing aircraft, the following solutions, offered by the Aerotoxic Association, could also be implemented:

• As bleed air is not presently filtered, installation of bleed air filtration systems would eliminate the problem, although a technically efficient system does not yet seem to have been developed.

• A less toxic oil formulation could lead to significant improvement. The French oil company NYCO is continuously developing such oils.

• Chemical sensors to detect contaminated air in the bleed air supplies – instead of human noses – would alert pilots to problems, allowing prompt preventive action.

The aviation industry is reluctant to acknowledge the problem and reform:

“It has become apparent that the primary safety consideration of the airlines is to keep airplanes flying – the safety of workers appears to have a very low priority to operational safety. Further, the regulatory agency involved in aviation safety (the Civil Aviation Safety Authority) admitted in evidence to the Senate Aviation Inquiry that its area of responsibility is airplane safety, not occupational health and safety.

Monitoring studies conducted by aircraft manufacturers and the airlines have failed to detect any major contaminants, although to date most monitoring studies have used inappropriate sampling techniques (such as air collection of poorly volatile contaminants) or inadequate methodologies (such as sample collection time, sample volume, storage of samples, not taking account of altitude). No monitoring has been conducted during a leak incident.

Attempts by airlines to address this problem through design, maintenance and operational improvements and through staff support and medical care have not been successful, and in the main, continue to be reactive and piecemeal. Obviously, in some cases, options such as improving engine design are not within the sphere of activity of the operators. The efficacy of recent modifications to the aircraft remains unknown, and leaks are still occurring, albeit at a reduced rate.

An admission was grudgingly made by one airline in 1998 that adverse exposures had been occurring, and that such exposures might cause irritation and transient effects. However, the development of long term symptoms is vigorously denied.

Civil aviation regulations clearly state that ‘the ventilation system must be designed to provide a sufficient amount of uncontaminated air to enable the crew members to perform their duties without undue discomfort or fatigue and to provide reasonable passenger comfort.’ The admission that irritation and transient symptoms can occur demonstrates non-compliance with the above rules.

Further, the adversarial and acrimonious manner in which some airlines have pursued workers compensation cases brought by staff with aerotoxic syndrome indicates a confrontational approach which is unlikely to be beneficial to all parties in the long term.”

The good news is the internet, social media, and consumer-driven platforms have demonstrated how we can all engage the system to transform the world. Not lastly, get yourself a mask with the capability to greatly mitigate exposures in the case of a leak or “fume event.”

yogaesoteric

July 8, 2019